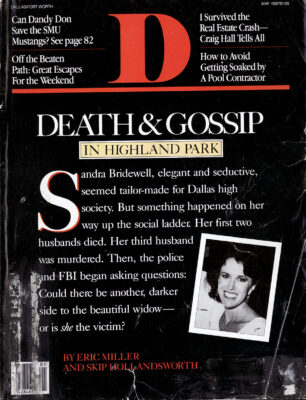

“Of all the interviewing I did, with all her closest friends, I could not find anyone who could think of a reason Betsy would have to shoot herself.”

–Bill Murphy, private investigator

Bobby Bridewell’s cancer doctor, John Bagwell, was one of the most distinguished physicians in Dallas, the kind of professional who would leave for the hospital before daybreak, come home at night for a quick dinner, and then go back to the office. His wife, Betsy, was the quintessential Highland Park housewife and mother. A former Highland Park High School cheerleader, Betsy worked on the Shakespeare Festival, belonged to the Junior League, was active at Highland Park Presbyterian Church, and taught a Bible class for children in her home while raising two children of her own.

“Her biggest goal in life,” recalls one neighbor, “was to have a No. 1 family.”

Betsy Bagwell lived the kind of stable life that Sandra Bridewell had long hoped to achieve. For whatever reasons, Sandra became very close to the Bagwells while Bobby Bridewell was dying of cancer. She depended on them as much after Bobby’s death as before.

One of Betsy’s closest friends, who talked to her shortly before she died, says that “it looked a little unusual how quickly she tried to get close to [John].” But Sandra also became very attached to Betsy, a sympathetic woman who was known for counseling and befriending many of her husband’s patients and their families. After Bobby’s death, Sandra even accompanied Betsy to Santa Fe for a short vacation. Sandra began to call Betsy “my new best friend,” says a Park Cities woman who knew both of them well during this period.

Nevertheless, the Bagwells were growing weary of her. Like many people who were once friends with Sandra, they felt she was trying to smother them, always asking them to do something for her. One Wednesday evening in July, Sandra telephoned Bagwell to tell him that her car had stalled while she was out running errands. Reluctantly, John agreed to assist Sandra. But when he got to the site, he saw a policeman getting into Sandra’s car. The car started immediately. Bagwell, who would later tell investigators that he believed Sandra had lied about the car trouble to lure him from his home, angrily told her to get out of their lives. He also told Betsy to stay away from Sandra.

But a few days later, on July 16, Betsy received a phone call from Sandra. According to a private investigator hired to look into Betsy’s death, Sandra was upset about a letter she had found written from another woman to Bobby. Sandra said the letter, discovered inside a frame behind a photograph, intimated that Bobby was having an affair. For Betsy, something didn’t seem right about the story. She told her husband about it that morning and brought it up again with two female friends over lunch at the Dallas Country Club. (Sandra has denied the existence of the letter to the Dallas police.)

According to police and private investigators, Betsy got another call that afternoon from Sandra. Again, her car had stalled, this time at a church, and she needed help. Betsy couldn’t say no. She drove Sandra to Love Field about 4:30 to pick up a rental car, but because Sandra had forgotten her driver’s license, she couldn’t get a car. According to police, Sandra said Betsy then took her back to her car at the church. Again, the car started. The police say that Sandra told them she then left Betsy and went shopping at Preston Center.

At 8:20 that evening, police found Betsy Bagwell in the terminal parking lot at Love Field, slumped in the driver’s seat of her 1980 powder-blue Mercedes-Benz station wagon with a bullet hole in her right temple and a .22-caliber revolver in her hand. The Dallas County Medical Examiner ruled the death a suicide.

No one who knew Betsy Bagwell could believe she had killed herself. According to investigators, Betsy had told her children early that afternoon not to “pig out” because she had dinner thawing in the sink. Moreover, the gun found with Betsy was a stolen Saturday Night Special, a cheap pistol registered to a deceased Oak Cliff man who had kept it in his glove compartment in his car. The man’s wife said the gun had been stolen sometime in the ’70s, but the couple never reported it missing to the police. Police and friends alike wondered how a woman unfamiliar with guns could come across a stolen handgun. Why didn’t Betsy Bagwell just go to a Highland Park sporting goods store and buy one?

But Dallas Police Department homicide investigator J.J. Coughlin, who supervised the case, says the county medical examiner called Betsy’s death “a classic textbook case of suicide.” Tests showed traces of gunpowder, blood, and tissue on her hand, leading to a ruling of suicide.

Still, those who knew Betsy were unconvinced. The death marked a turning point in the way Park Cities people regarded Sandra Bridewell. Suddenly, they were very apprehensive.

“When the first husband died, people felt sorry for Sandra,” says well-known real estate agent Thomas McBride. “When husband No. 2 died, they still rallied around Sandra.” But when Betsy Bagwell died, he says, people grew wary of Sandra. “She became quite a mysterious woman, and people were beginning to realize that the only things they really knew about Sandra were the things Sandra had told them.”

Was there another Sandra Bridewell, a black widow with a fatal bite? Or was Sandra a victim of circumstance, a maligned target of Highland Park rumors? Neither the police nor the private investigators found any evidence indicating murder. Friends report that Sandra seemed staggered by the deaths of her husband and best friend. If she heard rumors, she didn’t lower her dignity to address them. Remaining in the big Highland Park home Bobby had left her, she tried again to pick up the pieces of her life. She bought a new two-seater Mercedes, and she used the memorials given in Bobby’s honor, amounting to nearly $50,000, to help establish a week-long summer camp, run by Dallas’ Children’s Medical Center, for children afflicted with cancer.

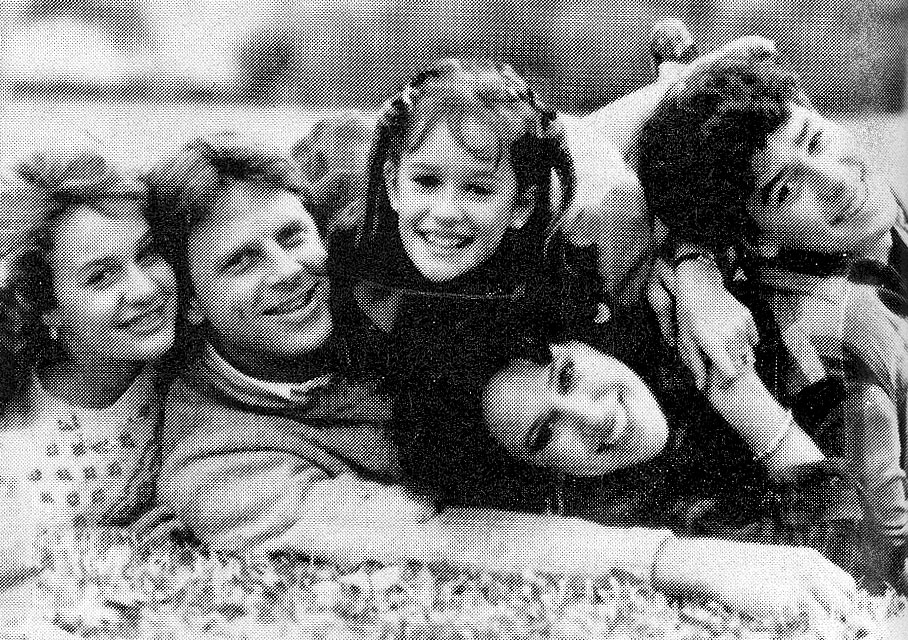

Sandra met new friends, and things began slowly to move forward. Her own children, amiable, well-behaved kids, seemed to be coping adequately with the second death in the family.

And then, in the summer of 1984, she met another man. His name was Alan Rehrig. He would soon fall in love with her. And then, he too would die.

THE THIRD HUSBAND

“Alan’s mistake was that he wanted money fast. His mistake was thinking he could quickly become a part of Dallas’ high society — and that left him gullible.”

-Bill Dodd, lifelong friend

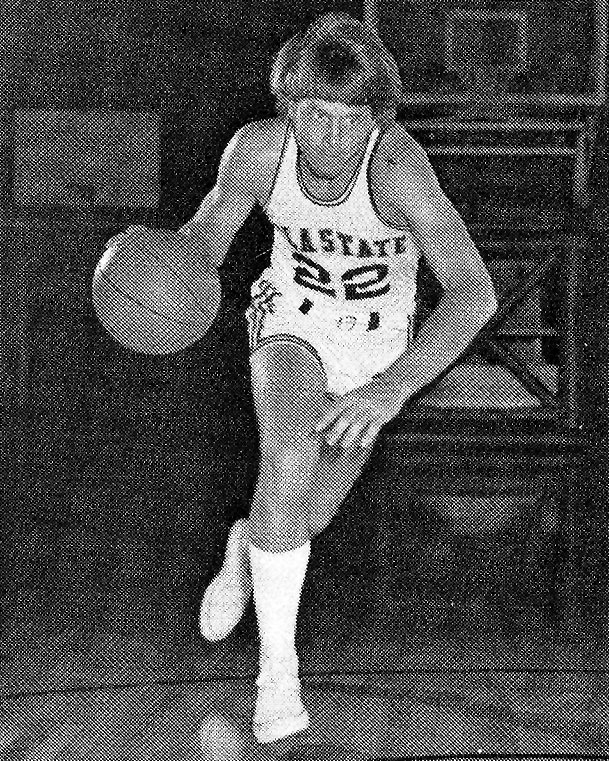

Growing up in the town of Edmond, Oklahoma, Alan Rehrig seemed to have everything going for him. They talked about him at the barber shop. Alan was the high school sports star who had made good, and as one of Sandra’s friends later put it, he looked “All-American cute.” His mother had a scrapbook full of clippings about Alan. Girls adored him. He became an All-State athlete in high school. On a basketball scholarship, he attended Oklahoma State University, where his mother was once homecoming queen. He also played on the college football team his senior year; a defensive back, he made an interception in the end zone during one game to save a victory for OSU. He became the first athlete since 1940 to letter in two varsity sports at that school.

With a teacher’s certificate in hand, Rehrig was planning to return to his home after graduation and work as a high school coach, just as his older brother did in another town. But just before he was to begin teaching at Edmond High School, Rehrig suddenly moved to Phoenix to take up golf, announcing that he wanted to become a professional golfer. Two of his old high school buddies had already made the PGA tour, and they persuaded Rehrig that he could do it too. Obviously, the move just didn’t make much sense — there was little chance that Alan would be successful as a golfer. But for a gifted athlete, the dreams of life in the arena don’t die easily.

For the first time in his life, Rehrig failed. He had to work nights as a waiter to make an income. After two years he returned to Oklahoma, where he decided to try the oil business, When the prices fell and the oil industry bottomed out in Oklahoma, Rehrig found himself out of money and looking for another job. His friends remember that he was feeling a little desperate. He was 29 years old, and he had gone nowhere.

In the summer of 1984, Rehrig decided to move to Dallas to work for an old college friend at Nowlin Mortgage. He reported to the commercial loan division, which acted as a broker between real estate developers and big life insurance companies wanting to invest their money. At a beginning salary of $24,000 a year, he started at the bottom of the ladder, running errands, doing the odd jobs. It didn’t seem like much, but he knew that down the road could come the opportunity to cash in on a big real estate deal.

The day after he arrived in Dallas, on June 2, Rehrig drove down Lorraine Avenue, one of the most beautiful streets in Highland Park, looking for garage apartments that he heard were often available behind the mansions. He saw a beautiful woman talking to her gardener out on the front lawn. Rehrig got out of his Ford Bronco, walked up to her, and asked if she knew of a place he could rent. Soon, the conversation got friendlier. She said her name was Sandra Bridewell.

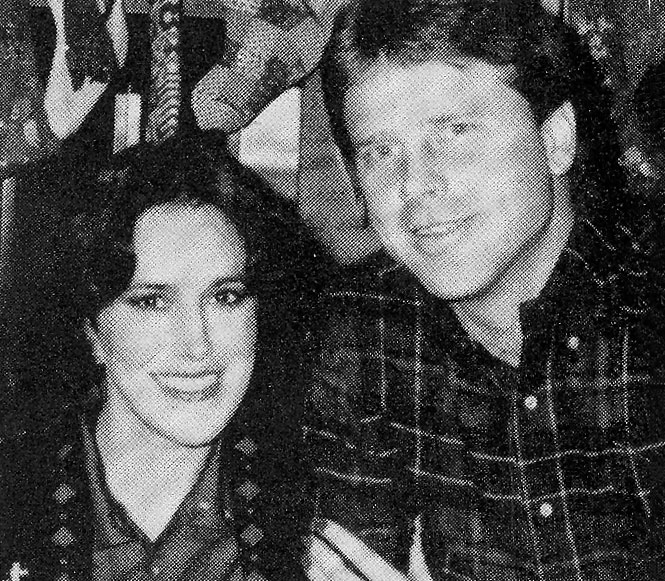

It was another rapid courtship. Five months later, the two announced their engagement, and on December 8, 1984, they were married in a ceremony at the Mansion. Alan was 29; Sandra was 40.

• • •

Alan told his friends and his mother that he thought destiny had brought him to Sandra Bridewell’s front yard so soon after his arrival in Dallas. He felt some pity for Sandra and her two previous luckless marriages — his friends at Nowlin Mortgage say Sandra had given him the impression that her first husband had died of a brain aneurysm.

Alan adored Sandra’s three children; as the relationship began to develop, Sandra would have the two girls come up to his office on occasion and bring him a flower. Recalls Phil Askew, Rehrig’s boss at Nowlin Mortgage: “One of her daughters, Katherine, would say to Alan, ‘I’m pulling for you and Sandra. We need a daddy.’ It would make his heart melt.”

Sandra was the kind of sophisticated, chic woman that Alan had never known in Oklahoma. Of course, it took a while for him to get used to her style: his mouth fell open at a tailgating party before a TCU football game when Sandra refused to eat hot dogs; they were too messy. Occasionally, without giving Alan much notice, she would fly to New York to shop or discuss an off-Broadway play that she was partly financing. The play, ironically enough, was a dramatic version of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, in which the main character himself is a murder suspect.

“Alan would call me,” recalls Kirk Whitman, one of Alan’s friends from Oklahoma who also moved to Dallas, “and you could tell he loved this stuff. He’d say. ’God almighty, Sandra just showed up in a limousine.’”

But there was another side to Sandra that Alan also found attractive, one that her suspicious ex-friends tended to forget about too easily. She was considerate and giving. She got Alan and his co-workers tickets on the fifth row for a Bruce Springsteen concert, and she was generous with her fourth-row season tickets to the Dallas Mavericks home games. When the wife of one of Alan’s co-workers became ill, Sandra drove over and babysat with the woman’s young child. Recalls Alan’s mother, Gloria: “We were thrilled with Sandra because she seemed so willing to create a Christian marriage. We thought Alan would be the greatest opportunity in the world for her.”

But few of Rehrig’s friends thought the relationship would lead to marriage. “Sandra was sensuous and sexual, and Alan was handsome, tall, and a stud,” says Dean Castelhano, a co-worker at Nowlin. “We thought she was using him as a showpiece, putting him in a tuxedo and taking him to the Mansion. You know, it was exactly the same thing as the older guy who likes to have a young beauty on his arm.”

Ironically, Sandra’s friends were also worried about her new relationship. Some thought Alan was a male gold-digger. “No one knew anything about him,” says Barbara Crooks. “I’m not real sure he wasn’t after money, and he saw in Sandra a way to set himself up financially.”

“The marriage, you could say, for a young guy just starting out, would be a leg up for him,” says Carolyn Day. “I mean, doesn’t anyone think it odd that he showed up out of nowhere at her doorstep, and then he hotly pursued her? And Alan did go after her. Sandra used to tell me how he kept ’coincidentally’ running into her. One time she was at the New York airport with her children on her way back from Europe, and there stood Alan, who said he happened to be on his way home from a business trip.”

It was a relationship, then, that sprang from uncertain beginnings. It would end in Rehrig’s death, and Sandra Bridewell would no longer be merely an object of neighborhood whispers. She would be the target of a police investigation.

• • •

Phil Askew says he vividly remembers an emotional scene in which he and Alan were driving back from a Mavericks game in the fall of 1984. Alan, in tears, said that Sandra had told him she was pregnant. He didn’t know what to do. Says Askew, “Alan said to me, ’Sandra’s pressing for a wedding, and I need time.’”

When Barbara Crooks hears this story, she says, “That can’t be true. Sandra had a hysterectomy before she met Alan. She told me that she sat him down before they ever got married and told him she couldn’t have children. She felt it was important that he knew that.”

Obviously, somebody was lying, but Sandra and Alan quickly arranged the wedding. According to Askew, a few weeks after the wedding, Sandra called the Askew home from a 7-Eleven one night. Alan was at Askew’s house; they had once again been at a Mavericks game. Askew says that Sandra told them she was returning from Baylor Medical Center, where that very night she had miscarried. No one had been at the hospital with her.

Says Bill Dodd, “I don’t think Alan had any intentions of marrying her until he learned she was supposedly pregnant. Then he was committed to her.”

“Alan was a dip,” says Sandra’s friend, Suzanne Sweet. “He used that marriage for the social connections it gave him.”

Whatever the reasons for the wedding, within six months the marriage had turned sour. Sandra had sold her home on Lorraine, and they were living in a duplex on Asbury in University Park. One of Sandra’s neighbors there, who had become a close friend, remembers listening to Sandra complain that Alan had become a financial drain on her. Sandra didn’t understand why he was spending so much money. Meanwhile, Alan’s friends at Nowlin Mortgage watched in astonishment as Sandra ran up more than $20,000 on Alan’s American Express card. “He was really being pressured by American Express,” says Castelhano. “They were calling him two to three times a day. You know, he refused to ever ask Sandra about how much money she had. He never wanted her to think he was interested in her that way. But this, he couldn’t figure out.”

Sandra and Alan argued over how to treat Sandra’s son, Britt, who had been receiving bad grades at Highland Park High School and was often staying out late into the night. Alan found his prized golf clubs missing one day from his Bronco and blamed Sandra. He was furious that she hadn’t written notes thanking guests for the wedding gifts. Sandra told friends that Alan was no longer sexually interested in her. Alan’s mother says she even received a phone call from Sandra accusing Alan of having an affair. Alan called Ron Barnes, a lawyer friend of his in Oklahoma, and reportedly said. “I don’t know who I’m married to.”

On and on it went. A neighbor of Sandra’s says that in the summer of 1985, Sandra began talking about how she was worried that Alan might kill her. According to the neighbor, Sandra said she had hired the famed DeSoto private detective, Bill Dear, to check Alan out. Several of Sandra’s friends recall Sandra’s saying that Alan was into serious gambling, or maybe even drugs. Alan’s friends say such charges are ridiculous.

During the first week of November 1985, Alan and Sandra separated. Alan moved in with the Askews, who lived in Richardson. According to Barbara Crooks and Suzanne Sweet, Sandra began investigating the possibility of divorce. A neighbor remembers that Sandra showed her a bill for a $1,000 consultation with one of the city’s most prominent divorce lawyers. But Sandra never filed for divorce.

“Here’s something I’ll never forget,” says Kirk Whitman. “Alan and I were sitting in a bar after they had separated, and it looked like the split was permanent. And he told me that Sandra was frantic that, in the divorce, he was going to take half of what she had. All Alan said he wanted was the stereo and his camping equipment.”

On December 5, two days before Alan disappeared, Whitman says the two of them went to a Mavericks game, where Alan again brought up Sandra’s refusal to pay the American Express bill. “Alan turned to me and said. ’You know, tomorrow I’m going to try to run down some financial data on her.’”

If he did, no one knows what he found. The following Saturday, Alan was supposed to meet Sandra at a mini-warehouse in Garland to help her move a few boxes from the University Park duplex. Alan hadn’t seen her in a month, and Askew recalls that he was nervous about the meeting. The two men planned to meet later that evening for dinner. At around 4:50 p.m., Alan left to meet Sandra in Garland.

Alan Rehrig never came back. At 6:15 that evening, Sandra called Phil Askew to say that Alan did not come to the Garland warehouse. She added that it was just like him to miss an appointment. He had done this to her before.

Though Alan Rehrig didn’t show up Saturday night or Sunday, Sandra did not file a missing person’s report. When Alan did not appear for work on Monday, the executives at Nowlin knew something was terribly wrong; Alan never missed work. Still, Sandra wouldn’t file a missing person’s report. Askew himself filed one at 8 p.m. on Monday with the Dallas Police.

On an icy Wednesday evening two days later, two Oklahoma City police officers were cruising through a remote area in the city’s southwest side. They found a Ford Bronco with Texas license plates parked next to an electrical substation.

Inside, shot twice with a .38-caliber pistol, was the frozen body of Alan Rehrig. It was December 11, 1985, one year and three days after Alan and Sandra were married.

• • •