“Here you are, a housewife worried about carpools and working at the school cafeteria, and along comes Sandra talking about someone throwing knives at her. None of this had ever happened to us.”

–Frances Shepherd, Highland Park mother

When David Stegall died, Sandra Bridewell was left with her 7-year-old son and two daughters, ages 4 and 1. She had no job. To some who knew her, it seemed as if the pretty young widow had nowhere to turn except to another man.

“She would often talk about men,” says Diana Reardon, “and how she needed men, and how her children needed a family. I mean, it was perfectly understandable. Sandra looked for men the way other people looked for a job. In the position she was in, it was her way of surviving.”

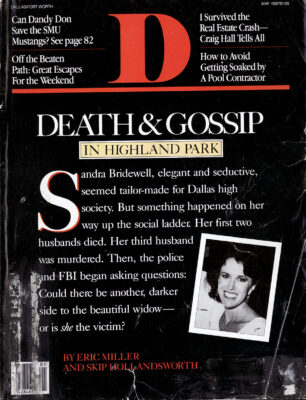

Some old friends of David Stegall’s resented Sandra, but many friends and neighbors were ready to help her. In time, Sandra began to go out again. And the Highland Park wives who set her up on dates with their wealthy divorced friends discovered something very quickly: Sandra, voluptuous and bewitching, was remarkably appealing to men. She knew how to flatter them, and she knew how to flirt with them. Those who have taken her out describe her allure in many ways — one calls it a “wonderful little-girl aura,” another calls it a “calculated femininity.”

Men looked upon her as they looked upon money: she was one of those things in life that was impossible to understand and useless to resist. “She had this sexy look to her,” recalls Lynn Price, the Highland Park woman who arranged Sandra’s first date with Bobby Bridewell, the man who would become her second husband. “It was sort of a smouldering style.”

“It wasn’t that she dressed in a provocative way,” says Yvonne Crum, a well-heeled Dallas socialite and public relations consultant. “She wasn’t that much prettier than other women. But men were spellbound by her. She had those great big eyes, and she’d stare straight at a man while talking to him, hanging on to every word, and it made him think he was the only person in the room.”

There was another thing people soon learned about Sandra. She was not shy in going after someone she liked. Says one friend who became close to Sandra after Stegall’s death: “Three months after David died, Sandra mentioned three men she wanted to meet. All of them were millionaires.”

Sandra’s defenders believe such stories are born out of jealousy. “It’s true Sandra has a few feminine wiles,” says Barbara Crooks. “Which of course makes her the type of woman other Highland Park women aren’t going to like. They don’t especially take to a woman who is warm and appealing.”

No doubt Sandra did make plays for rich men. Says a Dallas banker who introduced Sandra to a wealthy bachelor friend from Arkansas: “He came back from his date raving about her. Then he caught a flight back to Arkansas on Monday morning. Monday night he heard a knock on his door. It was Sandra. She had followed him home. It was an ugly scene because my friend was with his girlfriend when Sandra showed up.”

A wealthy Dallas investor met Sandra at Northwood Club in 1975. He recalls that she came on very strong right at the start. “She was sweet to the point of being gooey. I remember one time when Sandra and I double-dated with my sister. It was only our third or fourth date together. She was ‘honey’ this and ‘love you’ that to the point where I was embarrassed.”

Perhaps Sandra’s most notorious relationship after the death of her first husband was with Steak and Ale founder Norman Brinker, who began dating Sandra while he was in the midst of a drawn-out divorce proceeding. While dating Brinker in the fall of 1976, Sandra became the apparent target of a harassment campaign. On one occasion, her duplex was broken into, and a threatening message was written in lipstick on a mirror.

Several women also recall that Sandra told them about a woman throwing a knife at her. The stories created the kind of stir that almost never permeates the normally sedate Park Cities community. Brinker briefly hired a bodyguard to protect Sandra. Eventually she was dragged into his divorce; she gave a December 1976 deposition in the case. What she said remains a secret. Brinker won’t talk about her, and his divorce file is missing from the Dallas County records morgue.

And so, by the time Sandra met Bobby Bridewell, a fun-loving, likable hotel investor, she was already the object of great speculation. In the conservative Park Cities, where houses are filled with fine furniture and old paintings and maids, where mothers drive Suburbans and fathers leave work early to coach their kids’ YMCA soccer teams, Sandra certainly stood out. There is a comfortable emotion in “the Bubble,” as Park Cities residents call their own protected community: they know their lives will be safe and sheltered. Many of the residents grow up and die in the same neighborhood. Which is why Sandra was a very different entity altogether.

A lot of the talk was cruel. And the truth was that many women loved having her as a friend. They milked her for details, then burned up the phones passing on new tidbits. “You hung on every word of her stories,” recalls one ex-luncheon partner, “because you never knew how they’d end up.”

“The thing you have to remember is how narrow Highland Park can be,” says Barbara Crooks, who now lives in New York City. “I grew up there all my life, and I know what happens — you see the same people at the same parties, you do the same things, and you need something to liven up your life. People look for a great gossip figure. And that’s what happened to Sandra.”

But none of her past mattered to Bobby Bridewell, the son of a rich Tyler oilman who was beloved among his friends for his partying and wild sense of humor. “He was the master of the grand gesture,” recalls his friend, Dallas entertainment entrepreneur Angus Wynne. “He was a great lover of rhythm and blues, and he would go to all the concerts. Of course, he’d be one of the few white people in the crowd, but he didn’t care. He’d dance in the aisles and imitate the performers. Once he jumped up on stage and threw his coat around James Brown.”

When Sandra, who had been scheming to meet him for weeks, popped out of a closet one evening at Bo and Lynn Price’s home while Bridewell was there for dinner, he seemed utterly delighted. It was late 1977, and Bobby was going through an ugly divorce. His first wife had announced that she was in love with her horse trainer. Many of his friends knew how much the wrecked marriage had devastated him.

Sandra came along at the perfect time for Bobby Bridewell. She loved to go out as much as he did, and she made a point of sharing his interests. When she started dating him, according to one of her friends from that time, she read several books on horse racing, knowing how Bobby loved the sport. “Sandra knew how to indulge Bobby,” says her friend Carolyn Day. “She let him have center stage. He was quite the entertainer and talker, and she let him have his role while she took a back seat.”

After a whirlwind romance, they were married on June 26, 1978. “Bobby was swept off his feet,” says Bo Price. Another good friend, the noted Dallas architect Phillip Shepherd, remembers that Bobby, vulnerable from the divorce, needed companionship. “She was a different kind of girl for him. She doted on him. I think Bobby knew that Sandra thought she was coming in for a lot of money, but that didn’t slow up the relationship.”

What many didn’t know was that Bobby had been sliding into a major financial crisis. He was involved in dozens of joint real estate ventures in the hotel industry, and almost all of them were failing as the 1978 real estate market bottomed out. By the end of 1978 he was bankrupt and had fallen more than $3 million in debt.

Still, say his friends. Bobby refused to be discouraged, and by 1979 he was starting to turn things around again with a unique hotel project. On a drive one day by the old Sheppard King Mansion, a 16th-century Italian-styled villa, an idea flashed through his mind. Why not convert the villa into a pricey hotel and restaurant? He sold Carolyn Hunt Schoellkopf on the idea, and her Rosewood Hotels Inc. purchased the property. Bobby stayed on as consultant to see his idea turned into reality when the Mansion opened for business in 1980. By then, a bankruptcy judge had released Bridewell of all his debts, and he was back to a six-figure income again.

Quickly, Sandra Bridewell found herself thrust even higher into Dallas society. Bobby’s circle of friends, most of them in their mid-30s, were well on their way to becoming some of the most prominent businessmen and socialites in Dallas. Sandra was given the chance to do the invitations for the exclusive Cattle Baron’s Ball. She was given the best table and fawned over at the Mansion. When she traveled to Houston, she stayed at the chic Remington on Post Oak Park Hotel, another of Bobby’s projects.

Bobby even adopted her children, giving them the distinguished Bridewell name. She bought such lavish gifts for her new friends, says Phillip Shepherd, “that it just seemed a little too much.” Lynn Price says, “Sandra became even more glamorous. It was like she did nothing that did not involve the finest taste.”

Many of Bobby’s friends found themselves liking Sandra. “She had a magic spell on people,” says one woman who was close to her then. “You”d find yourself doing little things for her — running errands, taking her children places. Then you’d wonder why you were doing it, when you knew she was down at the Mansion having lunch.”

But the friends continued to help Sandra — especially after the shocking news came in 1980 that Bobby Bridewell had been diagnosed with lymph cancer. The ill-fated Sandra Bridewell, who seemed on the verge of establishing herself in society, was plunged into yet another tragedy. At first, Bridewell continued to work at his usual frenetic pace, seemingly undaunted by the heavy doses of chemotherapy he was receiving. But by 1981, he was losing weight and spending more time in bed.

To understand how Bridewell’s death made Sandra the object of more whispering and speculation, realize that Bobby Bridewell was adored by his peers. He was like a minor figure in a Fitzgerald novel, wearing loud sport coats, laughing harder than anyone in the room, always the last to leave the party. In a 1980 videotape of Phillip Shepherd’s 40th birthday party, a group of women sang a song in tribute to Bobby. The guests knew by then that the cancer was going to kill him, but they laughed and talked during the song. Still, even in the grainy footage, one can see Bobby’s friends look vacantly at him, as if lost. Nearby, Sandra sits on a couch, weeping softly with her hands to her face.

Bobby Bridewell’s last months should have evoked the kind of love and warm generosity that emerges in people during misfortune. Instead, a deep bitterness grew in Bobby’s friends, and it was directed at his wife — for while Bobby lay dying, Sandra Bridewell was remodeling their Highland Park home.

To some in the Park Cities crowd, Sandra’s actions were outrageous. “That winter before he died, the heat didn’t work in their home,” says a woman who was close to Bridewell. “And here was Sandra redoing her garden room and the wallpaper and what have you. So I brought over some spare electric heaters and a down comforter to make Bobby feel more comfortable, and Sandra wasn’t appreciative of the down comforter because it didn’t look pretty enough.”

“Oh, that’s a crock,” says Barbara Crooks in defense. “They were fixing up that house long before Bobby got sick. And he asked that it be done.” Says another lifelong Highland Park resident who couldn’t understand the complaints of Bobby’s friends: “Okay. Sandra’s actions might not have been the most appropriate thing to do, but it wasn’t like she was being immoral. Bobby’s crowd was just looking for something to hold against her.”

In the spring of 1982, Sandra asked Marian Underwood, a neighbor who was a retired teacher, if Bobby could stay for about a week in one of her spare bedrooms while Sandra had central air conditioning and heat installed in her home. Bobby never returned home. He stayed at the Underwood home for three weeks, until Bobby’s father got angry at Sandra and moved him into a suite at one of his motels, the Twin Sixties Inn on Central Expressway. Marian Underwood, who loved the Bridewells, also had a falling out with Sandra, as did many of Sandra’s friends who had taken care of her children or bought her groceries during Bobby’s illness, and felt little appreciation in return.

“Sandra was so demanding with your time,” says Diana Reardon. “She’d call you constantly and not get off the phone, or she’d come over and never leave. Even if you had something to do, she would stay and talk, no matter how politely you said that it was time for her to leave. It got to the point where you’d have to escort her to the door and shut it in her face. Then she’d call you up crying, telling you how terribly you treated her.”

Bobby remained in the motel room until late April, then spent the last two weeks of his life at Baylor University Medical Center. The remodeling continued on the house.

Bobby died at age 41 on May 9, 1982. A few weeks later, Sandra left for a Hawaiian vacation with her three children. She needed to get away from a world that had come crashing down around her.

Though Sandra might not have realized it, she was quietly being ostracized from her cliquish society. The talk was snowballing, bringing an avalanche of rumor and innuendo to bury her reputation. Sandra had strayed too close to the boundaries of good taste in the reserved Park Cities community. A few months later, the talk would become tinged with fear when one of Sandra’s friends was found dead in a Love Field parking lot.