PROFILE OF A KILLER

by Nan Cuba and Dr. Joel Norris

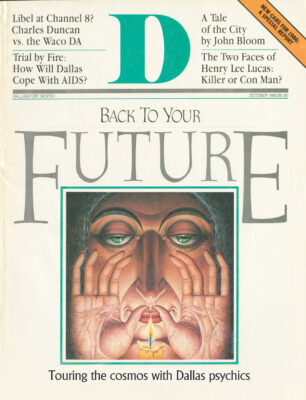

SHENRY LEE Lucas a vicious murderer of numerous strangers across the country, or a down-and-out drifter who became a scapegoat for overanxious lawmen? For a year and a half Lucas and many law enforcement officials claimed he was the most prodigious killer in history, with as many as 3,000* victims. Then Dallas Times Herald reporter Hugh Aynesworth cried hoax, Lucas decided he didn’t want to be put to death by the state and Attorney General Jim Mattox helped start a grand jury investigation in McLennan County. During those days, Lucas told reporters, “I didn’t kill nobody excepting Mom,” but privately he said that he suspected he had been captured by a death cult and that McLennan County District Attorney Vic Feazell and others were forcing him to deny the truth.

Despite Lucas’ flip-flops, we believe that ample scientific evidence supports our conclusion. Lucas fits the mold of the classic serial killer, and was capable of multiple murders.

Following many phone calls, much discussion, extensive arrangements and seven postponements, on Jan. 28,1985, these writers had Lucas flown from Georgetown, Texas, by private DPS aircraft to Dallas for an all-day series of neurological tests and examinations at Presbyterian and Baylor hospitals. The results: Lucas fits the neurological, sociological and biochemical blueprint of the serial murderer.

Lucas’ schedule included the taking of blood and urine samples, a CT Scan, examinations by a neurosurgeon and a neurologist, an EEG (electroencephalogram) and finally an MRI (magnetic resonant imaging) test at Baylor. All of these tests were selected because, for the first time, doctors suspected a neurological basis for Lucas’ behavior. The participating doctors, neurosurgeon Phillip Williams and a staff neurologist from Presbyterian and Dr. Stephen Harms Jr. at Baylor, all willingly agreed to perform the requested tests because of “curiosity, a belief that the project was not a scam and for use in their own research,” says Doug Hawthorne, president of Presbyterian Medical Center.

At about 4:30 that afternoon, when the tests were finished, Lucas was flown back to the Georgetown jail, and we had the test reports and photographs mailed to Dr. Vernon Mark, director of neurosurgery at Boston City Hospital and president of the Center for Memory Impairment and Neurobehavioral Disorders.

AS AN ATTEMPT to stimulate research into the serial killer phenomenon, these writers compiled a journalistic report that includes experts’ theories from a variety of disciplines (neurologists, sociologists, psychologists, criminologists, journalists, geneticists, attorneys, biochemists, etc.). Progress in the understanding of serial killing-its causes, symptoms, treatment and prevention-is impossible until such an interdisciplinary approach is taken.

For our report, we defined a serial murderer as someone who kills three or more people during a period longer than two weeks. We believe each of the murders is a recapitulation of childhood horrors, a dark rebirth of tangled emotions and damaged physiognomy fused by existential anxiety of the deepest nature. According to conservative FBI statistics, the body count from these homicides is 5,000 a year, with half of these victims being children under 18. Since 1960, 135 serial killers have wreaked havoc in America, while the rest of the world has produced only 45.

As defined in the Norris Serial Killer Profile, serial murderers often have an average or above-average IQ, are approximately 28 years of age, and, either in solitude, with a partner or sometimes in “families” or cults, go trolling the pedestrian byways, driven by an insatiable compulsion to slaughter people they usually have never met. Potentially creative people, most are viewed by their neighbors as pleasant, sometimes charming, and many are avid media fans and police buffs. They are almost all drug abusers and have an unhealthy reaction to alcohol. Few have ever been married or have children. Most have memory problems and, as a result, are often caught telling lies, which causes ambiguity and frustration for those who are trying to understand them. They have compulsive personalities, keeping scrapbooks, diaries or souvenirs of the murders, while also racking up high car mileage as they continually cruise potential murder sites.

Their families represent all socio-economic levels, but the serial killers were each in some way isolated, unable to interact normally with others. Most of the killers made frequent trips to hospital emergency rooms or pediatric offices when they were very young, following both a pregnancy and a birth which were suffused with trauma. A significant number of them were reared by adoptive parents, and many were offsprings of drug abusers. Fitful and agitated as children, almost all were victims of abuse and/or negative upbringing, having either a violent father and a passive mother or a passive father and a controlling mother. In many instances, the mother required periodic psychiatric treatment and either had a fixation on fundamental religious beliefs or a dependence on the health profession, drugs or alcohol. As a result of their family histories and experiences, almost all serial killers are confused about their sexual identities.

A large percentage of the extraordinarily violent show one or more symptoms of minor neurological impairment, such as hallucinations, illogical thought processes, paranoid ideation, isolation or withdrawal, excessive crying, incontinence, sleep problems, coordination problems, history of seizures, reading or mathematical disabilities and headaches. They also demonstrate one or more psychiatric symptoms, like suicidal behavior, serious assault, cruelty to animals, setting fires or aberrant sexual behavior. Lastly, these people have poor nutritional habits, consuming large proportions of refined carbohydrates like sugar and flour, which in turn contribute to their inevitable body chemical imbalances.

SOME EXPERTS BELIEVE genetic factors make certain people susceptible to criminal behavior. Others cite prenatal and perinatal problems as contributory. Some neuropsychologists claim sensory deprivation, or the absence of touching and moving an infant, can induce significant changes in the biochemistry of brain cell functioning.

According to Alice Miller, a Swiss psychoanalyst, a key element in the making of a murderer is his treatment during childhood. Abusing a child while telling him it is “for his own good,” says Miller, is particularly damaging. After receiving abuse, the child is not allowed to express his anger, but instead is forced to show gratitude for the caretaker’s “good” intentions. This repressed suffering and rage later resurface; the killer recapitulates his childhood trauma in the form of a violent act.

Dr. Mark, who wrote Violence and the Brain, believes violence is a symptom of a disturbance in the brain mechanisms that control, initiate and suppress violent behavior. The mechanisms are located in the limbic brain, which is a small and primitive section regulating emotions and storing some memory. The disturbance is caused, he says, by brain disease which is either genetic or acquired by a head injury, lack of oxygen, chemical imbalance, viral infection or tumor. Violence might also result from temporal lobe epilepsy, signaling malfunction in this same impulse-control area.

Criminologists Diana Fishbein and Stephen Schoenthaler have separately studied nutrition therapy and its relation to brain function and antisocial behavior. Similar research by Dr. William Walsh, a chemist at the Health Research Institute near Chicago, suggests that trace-element patterns signal a predisposition to violence. In two studies with violent men and their nonviolent siblings, he found that the violent males fell into two categories: the episodically violent (such as the McDonald’s restaurant sniper) were high in copper, but low in sodium and potassium; the antisocial sociopathic males demonstrated the reverse pattern.

THIS INFORMATION, coupled with the results of the Dallas tests on Lucas, leads to an obvious conclusion: Lucas could be-probably is-a murderer of many people.

According to Dr. Mark and Dr. Paul New, a neuroradiologist and professor at Harvard Medical School, the Dallas tests produced significant results. These experts found small contusions and tissue loss in the frontal lobe, as well as temporal lobe abnormalities that were more pronounced on the left side. Mark says some brain disorders change a person’s behavior in regard to whether he becomes aggressive under stress or runs away (“fight or flight”). Personality disorders, such as the demonstration of a lack of conscience, and aberrant behavior called sociopathy can result. In other words, brain disorders can create a sociopath.

“Henry Lee Lucas has a characterological problem. He obviously has no compunction about killing. He has been caught lying repeatedly. Lucas has a great tendency toward sociopathy,” Mark says. In reference to the Dallas tests, he adds, “There are small abnormalities in the frontal lobes, temporal lobes and in the parts of the brain that are related to emotional control. The significance of this in Lucas’ case is unknown because so many factors work together to generate human behavior, and abnormalities of that system [like Lucas’] could influence how an individual behaves under stress with the possible explosion of inappropriate aggressive behavior.”

In New’s opinion, Lucas’ brain damage was the direct result of a head injury that occurred between the ages of five and 10. This is significant since Lucas claims his mother smashed a two-by-four across the back of his head when he was seven. The next year, his older brother accidentally cut Lucas’ face and eye with a knife; Lucas eventually lost that left eye after another blow to the face.

Regarding Mark’s theories of temporal lobe epilepsy as a signal of brain dysfunction, Lucas told an Austin psychiatrist in a videotaped interview that he had what might have been seizures as a child. He has described often the repeated sensation of floating off his bed into the air. Most psychiatric investigators have interpreted this behavior as a delusion and therefore schizophrenic in origin, but it can also be interpreted as temporal lobe seizures.

Lucas’ hyperreligiosity and hypervigi-lance, or excessive concentration on death cults and newfound Christian beliefs, is another symptom of possible temporal lobe damage. Even his descriptions of a fluctuation in body temperature before each of the murders could relate to neurological dysfunction.

Other experts suggest the possibility of damage to the commissural fibers that unite the two hemispheres of Lucas’ brain. If this section, called the corpus callosum, has been severed or impaired, the left side of the brain is unable to exercise proper control over the more primal right side. This problem, called the Jekyll and Hyde syndrome, sometimes results in multiple personality. Indications of this as a possible diagnosis are Lucas’ ambidextrousness and the fact that he has said he hears voices. These factors certainly suggest the need for further testing in this area.

In accordance with the criminologists’ theories on nutritional habits affecting antisocial behavior, Lucas’ diet during 1970 to 1982, the years during which he claims to have killed hundreds of people, included almost daily consumption of alcohol, a variety of drugs, pots of coffee, five packs of cigarettes, peanut butter and cheese.

The chemist, Dr. Walsh, analyzed locks of Lucas’ hair to determine the prisoner’s category of body chemistry. “His cadmium concentration is more than 30 times the population median value, and is the highest level we have ever observed in a human being out of thousands tested,” says Walsh. According to his research, this places Lucas well within the sociopathic group. Walsh also suggests Lucas has extreme personality deterioration after alcohol ingestion. This is significant since Lucas claimed, “I was drinking before every one of my killings. I was never sober.”

The killer’s love-hate relationship with his mother parallels Miller’s theories. Viola Lucas never allowed her son to express emotion; even at his father’s funeral, Henry was not allowed to cry. Then, in 1960, he stabbed Viola, killing her. A 1961 Ionia State Hospital report says Lucas admitted to having two different feelings toward his mother. “At times I feel sorry for her,” he said, “and at other times I feel a grudge against her because of her dirty life.”

Miller’s theories, carried further, explain Lucas’ potential for creativity and, despite a dull-to-normal range of intelligence, his ability to manipulate a variety of individuals. His childhood trauma has trained him to compensate for his dyscontrol by focusing all of his energy on the survival of each moment and maintaining the semblance of a healthy, integrated identity. Instinctively, Lucas is constantly scrambling for acceptance and sanity; his desperate, primal drive has created a nature which is chameleon-like and mercurial.

A result of these survival skills is his free-floating aphasia, memory problems that appear and later disappear. He has recalled minute details of many crimes, yet he can’t remember the names of any victims. On the Dallas testing day, Lucas could not even recall the names of President Reagan or former President Nixon.

And Lucas appears to be confused about his sexual identity, claiming to be heterosexual, yet admitting to homosexual activity in prison and with his partner, Ottis Toole. Lucas also claims to have a history of bizarre sexuality, including incest, bestiality, rape and necrophilia.

He also exhibits unusual thought processes which include grandiosity, delusions and assumptions based on little concrete information. As an example, Lucas first confessed to the Williamson County Orange Socks murder because he wanted to be put for death for a crime he did not commit. Therefore, he reasoned, he would be able to join his common-law wife in heaven. And the scope of his death-cult tales appears to be quite exaggerated. He has even “confessed” to the contract killings of several government officials, all of which he said are recorded in a buried black book which cannot be found.

As is common with this personality type, Lucas’ behavior in prison appears more controlled. Serial killers usually function better in prison and often become bonded with their captors. Therefore, it is understandable that Lucas’ statements vary according to the attitude of the group in charge of him at the time.

No wonder he confessed to some 3,000 murders while working with the Texas Rangers in Georgetown-his emotional and physical well-being demanded it. And we are not surprised that later he announced on Good Morning America and testified to a McLennan County grand jury that the confessions were coerced and he really killed no one-again, he was conforming to the dictates of the moment. His confusion and threats of suicide at that time demonstrate his period of transition. Tragically, his survival instincts and memory problems will likely make it impossible ever to know for sure the number of strangers he actually murdered.

Finally, like other killers, Lucas perceives his victims as objects rather than people. “It was like burning wood,” he said about cremating Kate Rich’s body, “like burning a piece of wood in the stove.”

Many hours of formal interviews and casual conversations with Lucas and others before he left Georgetown were used to compile the following question-and-answer exchange. Some of the responses are quoted from a session Lucas had with a psychiatrist for his defense before the April 1984 trial. Much of the inserted information was gleaned from medical reports, interviews and legal documentation. Interviews with childhood acquaintances and a former schoolteacher confirmed Lucas’ childhood horror stories.

As a child, Lucas lived with his mother (a Chippewa Indian and part-time prostitute), her pimp (a double amputee he calls his father but believes actually was not) and his older brother. Lucas was the last of seven children by the snuff-chewing, alcoholic Viola; his five half brothers and half sisters lived elsewhere. His home was a three-room, dirt-floor log cabin in the hills of Virginia that had no plumbing or electricity. The boys did all the chores and made and sold moonshine; the father sold pencils and skinned mink; Viola sold her body, often forcing Henry, his brother and their father to watch. She beat each of them constantly, and Henry grew to hate her, claiming he “never had a mom.” This loathing later became the catalyst for homicide.

Q: What was your childhood like?

Lucas: When I first grew up and can remember, I was dressed as a girl by my mother. I had hair like a girl. And I stayed that way for two or three years. And after that I was treated like what I call the dog of the family. I was beaten; I was made to do things that no human bein’ would want to do. I’ve had to steal, make bootleg liquor; I’ve had to eat out of a garbage can. I grew up and watched prostitution like that with my mother till I was 14 years old. Since then I’ve started to steal, do anything else I could do to get away from home… and I couldn’t get away from it. I even went to Tecumseh, Michigan, and I started livin’ up there, and my mother came up there and we got into a argument in a beer tavern. From the beer tavern my sister brought her back to where I was livin’ and we got into it again there, and I killed her. She done pushed me beyond the limit of really caring. I don’t say it’s her fault; it’s her life. I was just stretched to a point where I wasn’t goin’ to be pushed no further.

Q: When you were a little boy, what was an average day?

Lucas: Well, lots of times I’d spend in the woods. I’d go out to play in the woods or I’d go walk nine miles into town. I’d walk to school, drag in wood, carry water for half a mile. That was my average day.

Q: As a child, did you have a puppy or a pet?

Lucas: No. Well, everything I had was destroyed. My mother, if I had a pony, she’d a killed it. If I had a goat or anything like that, she killed it. She wouldn’t allow me to love nothin’. She wanted me to do what she said, and that’s it. That is, make sure the wood is in, the water’s in, make sure the fires are kept up; the dishes when you got through eatin’, I’d have to wash ’em. Work. That’s it. And I’d have to stand and watch her have sexual acts with a man.

Q: How would she make you watch?

Lucas: You just stand there and watch! Stand in the house, or she would beat my brains up if I didn’t. Some people say they gonna give a whippin’ with a switch or somethin’; she’d use sticks! She didn’t know what a switch was! When she went and got a switch, she went and got a handbroom stick. She’d wear them out.

Q: Tell us about your dad.

Lucas: Everybody called him “No-Legs.” He scooted around on his behind and sold pencils. He was good to me. When he had money, he’d give it to me. If I wanted to go to the movie, he’d take his alcohol money and give it to me.

Q: Did he also have to watch your mother during the act of prostitution?

Lucas: Oh, yeah. He couldn’t do anything about it either; she’d knock his brains out as soon as she would mine. He drank just to get away from it. He’d go out and lay in the snow to get away from watching her. That’s what made him die… .He laid out in the snow and caught pneumonia, and he was drunk and died.

Q: Do you think you have a damaged brain?

Lucas: Oh, I know I have! They’ve checked it out. Right there across the back of the head here… .I got a lot of stitches.

Q: How did it happen?

Lucas: Well, Mom knocked me over the head with a two-by-four, and I stayed out for about 36 or 38 hours before I came to. I was about seven, eight years old. When I was in the hospital, she told the doctor that I fell off a ladder, and the doctor accepted it. But later I proved to them what did happen.

Q: Why did she get so angry with you?

Lucas: Because I wouldn’t go pick up a stick of wood. And she took the two-by-four and went and knocked my brains out with it. It made the bone and all wide open.

Q: Have you ever had a seizure?

Lucas: I used to have something. A long time ago when I was a child. What I remember was that it was like somebody layin’ down and stompin’ you, and you keep on fightin’ to get away from ’em. I didn’t know anything happening around me. I couldn’t hear really. It was like being in a different world. I used to float through the air when I was a kid, too. I used to be layin’ in bed, just feel like you’re floatin’ right off the bed up in the air. Just feel like I could fly. It’s not a nice feeling; it’s a weird feelin’.

Q: Do you think you are crazy?

Lucas: I’ve got problems, but as far as being crazy, I couldn’t tell you. I can’t say whether I’m crazy or whether I’m not crazy. I don’t think that’s something that anybody can do really. Sometimes I hear stuff when there’s nothing around. I’ve heard my name called and there ain’t been nobody with me.

Lucas murdered his mother in 1960 and was taken to the state prison of southern Michigan. Following several suicide attempts there, he was sent to the Ionia State Hospital where he stayed for almost five years. He was paroled from prison in 1970. Lucas said that during this period a transition in him took place, and upon his release he was blatantly determined to kill people.

Q: How could your mother be responsible for getting you sent to Ionia when she was already dead?

Lucas: I kept hearing her talking to me and telling me to do things… and I couldn’t do it. Had one voice that was tryin’ to make me commit suicide, and I wouldn’t do it. I had one tell me not to do anything they told me to do. And that’s what got me in the hospital, was not doing what they told me to do.

Q: How did you spend your time in Ionia? Lucas: Walk around on the floor and shine the floor with your feet. They put these cloths over your feet, and you’d have to walk the floor, shine the floor. Had to, I’m not kiddin’; they’d beat your brains in if you didn’t.

Q: When you heard your mother’s voices, did you actually hear these voices, or was it just your imagination?

Lucas: Now I know it was my imagination, but back then it was just as real as if I had sat there and heard it. I wouldn’t see things; it was just sounds.

Q: What did you learn from this experience?

Lucas: How to be mean! I learned every way there is for law enforcement. I learned every way there is in different crimes; I studied it. After I got out of that hospital, they put me in the records room. And every record that jumped through there, I would read it, study it and see how what got who caught.

Q: Why were you reading those things?

Lucas: Because I intended on doing them when I got out. I was planning. I knew I was going to do it [kill]. I even told them I was going to do it! I told the warden, the psychologist, everybody. When they come in and put me out on parole, I said, “I’m not ready to go. I’m not going.” They said, “You’re going if we have to throw you out.” They threw me out of the prison because it was too crowded. So, I said, “I’ll leave you a present on the doorstep on the way out.” And I did it, the same day, down the road a bit. But they never proved it.

Q: Whom did you kill?

Lucas: A woman down in Jackson, Michigan. I took her up next to the prison and killed her, within walking distance of the prison. I gave them something they gonna remember! Then when I cleared it up here awhile back, they said, “Well, I didn’t think that you were going to do that.” They know now that I meant what I said. I was bitter at the world. I hated everything.

Q: Do you have difficulty talking and relating to people?

Lucas: When I’m around people, I feel tense, nervous. I guess it’s because I haven’t been around people. Most of the life I’ve lived has been alone. I have troubled talkin’ to them; I always have. I don’t think there’s a doctor in the world that’s going to go against another doctor’s word. They say there’s nothing wrong with me, so that’s the way it is. I don’t feel there’s something wrong with me, I know it! People don’t do the things they do unless there’s something wrong with them. I just thought there’s no way I could kill somebody, so it’s not that. Something pushes me into doin’ it.

A1961 Ionia State Hospital report states that Lucas claimed his first sexual experience occurred when he was 15 with the 28-year-old wife of a half brother. He also said this same half brother soon after introduced him to bestiality, slashing the throats of calves and dogs before the act. According to Lucas, none of these experiences was either exciting or satisfying. Statements by Lucas about his necrophilia vary. He has claimed that five percent of his victims were murdered so that he might have sex with the bodies; however, he has also said he killed no one for the purpose of sex. At the time of his mother’s murder, Lucas said he had sex with Viola’s body, but he now denies this. He was married for two years, but that ended, according to one report, following his attempts to sexually abuse two stepdaughters. He was engaged in 1960, a relationship which contributed to his mother’s death. He murdered his common-law wife, Becky, and strangled his first victim when he was 14 after attempting to rape her.

Lucas: Sex is one of my downfalls. I get sex any way I can get it. If I have to force somebody to get it, I do. If I don’t, I don’t. I rape them; I’ve done that. I’ve killed animals to have sex with them. I’ve had sex while they’re alive. It’s about the same thing as far as having sex. I’ve killed nobody for sex.

Lucas said he did not know why he murdered so many people. He believed he was demon-possessed, a result of his death-cult training. He described his motivation as a force that drove him to perform evil.

Q: How do you see the victim at the time of the murder?

Lucas: It’s more of a shadow than anything else. You know it’s a human being, but yet you can’t accept it. The killin’ itself, it’s like say, you’re walkin’ down the road. Half of me will go this way and the other half goes that way. The right-hand side didn’t know what the left-hand side was going to do.

Q: Do you think you have a conscience?

Lucas: I do now. I feel each one of these victims I go back to; I got to go and relive each victim. It’s like going back and completely doing the crime all over again.

Throughout his lifetime, Henry Lee Lucas has been examined and tested by numerous psychiatrists and psychologists. He has been diagnosed as schizophrenic many times. But in the three murder trials during which his sanity was questioned, he was found legally sane each time.

Q: What would you like to say to psychologists?

Lucas: Change your methods of examining people. There’s no way that a person can actually go and sit down and examine a person, and make an accurate, legal reading of that person. He can tell maybe what a guy thinks, what he sees, but he can’t tell whether there is anything wrong with that person.

PROFILE OF A CON MAN

by Hugh Aynesworth and Jim Henderson

NAN CUBA AND Dr. Joel Norris have embarked upon an unenviable journey, a search for the essence of murderous madness by rummaging through the tortured cranium of Henry Lee Lucas. Their work, they say, is “an attempt to stimulate research into the serial killer phenomenon,” and we are asked to comment on their theories and conclusions.

Our task is no more enviable. It was our lot to report the fraud of Lucas’ multiple murder confessions, and so we approach the Cuba/Norris article with the conviction that if Lucas is a serial killer at all, he is, on the scale of 20th-century atrocities, a very minor one.

It is far beyond our area of expertise to comment on the serial killer profile as outlined by the authors, or the brain scan results as reported by them. We do not doubt now, nor have we ever doubted, that the mind of Lucas is somewhere outside the range of normal. He remains an enigma, and we, as much as anyone, long for a rational interpretation of his behavior.

Cuba and Norris, however, present us, and all of their readers, with an odd leap of logic that does not square with the facts. They outline their serial killer profile, quote a few experts and state flatly that their information, “coupled with the results of the Dallas [brain] tests on Lucas, leads to an obvious conclusion: Lucas could be-probably is-a murderer of many people.”

Lucas could be the killer of many people, but probably is not. In the entire prolonged Lucas saga, there has not been a single shred of court-worthy evidence that Lucas has killed more than three people. Prosecutors from coast to coast have had ample opportunity to come forward with such evidence and, so far, they have not. In fact, prosecutors who once obtained indictments based solely on Lucas’ confessions have now begun to dismiss those indictments.

The troubling leap of logic Cuba and Norris offer is this: Because Lucas may fit some aspects of the serial killer profile and because he has certain brain abnormalities, he must, therefore, be a serial killer. To be sure, Lucas does not fit much of the profile. He does not have an average to above-average IQ. He is well beyond 28 years of age. He has no history of being an avid media fan or police buff. He has been married and does not appear to have a memory problem (lawmen have described his memory as “phenomenal”). His personality is anything but compulsive (he kept no diaries or souvenirs of his alleged crimes). Millions of Americans fit the serial killer profile as well as Lucas, yet they are not serial killers.

There may be millions more who suffer similar brain impairments, yet they are not serial killers. Psychological workups and brain scans may be useful diagnostic tools, but they are hardly evidence of mass murder. The most compelling evidence is to the contrary, that Lucas could not possibly have committed the murders he once claimed.

So we have to approach the Cuba/Norris research with the judgment that they are advancing an illogical theory to support an impossible thesis.

TO BEGIN WITH, the article contains questionable assumptions. It relies to a great extent on the statements of Lucas, whom the authors acknowledge is a sociopathic liar.

But it is the premise that is disturbing-the belief that in Lucas’ damaged brain we might find clues to understanding the forces that drive men to act out a society’s worst nightmares. At best, Lucas is a poor subject for such inquiry.

Cuba and Norris begin with an important caveat-defining a serial killer as one who has killed at least three people during a period of more than two weeks- that they quickly abandon with repeated suggestions that Lucas has killed the hundreds to which he confessed and which lawmen have credited to him.

To analyze Lucas as the typical serial killer, the authors downplayed the large body of evidence suggesting that he is not a typical serial killer, if he is a serial killer at all. In fact, he may qualify as such only under the minimum requirement of the Cuba/Norris definition. There is evidence that Lucas killed three people. He may have killed more, but only his own discredited confessions support that theory.

STILL, THE TAKING of three lives is no small matter and surely there is value in the study of all aberrant behavior. That behavior, however, must be studied within a factual context. Our most serious quarrel with the Cuba/Norris article, aside from the difficulty of placing Lucas in the area of crimes he claims to have committed, is the first-paragraph assertion that “Dallas Times Herald reporter Hugh Aynesworth cried hoax. . .” Neither Aynesworth nor the Dallas Times Herald “cried hoax.” The newspaper documented the hoax in painstaking detail. It was not just alleged that Lucas pulled off monumental fraud; it was proven conclusively. The investigation of Lucas’ life from 1975 to 1985 was perhaps the most thorough and productive ever undertaken by a daily newspaper. By disregarding the evidence of a hoax, Cuba and Norris distort the value of their research.

If one is compelled to understand the mental workings of Henry Lee Lucas, one must proceed under the assumption that while he may be a killer, he entered the American conscience in a far different role. He was theatrical beyond belief, yet there was pathetically little questioning of his credibility. He persuaded otherwise intelligent investigators that he could drive 11,000 miles in a single month to commit six murders and a kidnapping. He convinced usually skeptical prosecutors that he could be in Duval County, Florida, and Douglas County, Nevada, on the same day. He made veteran and traditionally cynical journalists believe that he could kill 200, 300 or more people and leave not a single clue. The authorities were left with only his word that he had committed the crimes. Lucas killed three people and got caught within months. But now we’re supposed to believe that he lied about hundreds of others and got away with it for nearly two years.

Nan Cuba was one of the first journalists aboard the Lucas-as-serial-killer bandwagon, and she has declined to accept the evidence that he was something else-a con artist and manipulator to rival Clifford Irving and Billy Sol Estes, rather than a murderer to rival the Son of Sam or the Hillside Strangler.

It is Lucas the con man rather than Lucas the killer who deserves the kind of analysis Cuba and Norris have attempted. We do not doubt that criminal or antisocial behavior flows from some damaged crevice of the psyche, from some mysterious brew of foul chemistry or mutation of cellular construction. Was it a great surprise when autopsies revealed that the brains of Jack Ruby and Charles Whitman were pocked with malignant tumors? It is not difficult to believe that Lucas suffered from “temporal lobe epilepsy” or damage to the “commissural fibers” uniting the brain’s two hemispheres or that his “cadmium concentration is 30 times the population median value.”

How, though, does such knowledge aid our understanding of Lucas the con man? He was an abused child. He was uneducated. He has an IQ of 87 and, according to the tests conducted at Presbyterian and Baylor hospitals, has traces of brain damage. Did those factors damn him to the life of a mass murderer, or did he survive in abject dereliction in spite of them? The evidence tends overwhelmingly to support the latter.

IF ONE CAN accept the evidence that Lucas was not the most vicious serial killer in U.S. history, then one should examine him in his true persona:

During the period when he was willing to own up to any crime the cops laid on the table, Lucas was questioned by an investigator from Delaware about the unsolved murder of a young woman there. Lucas was shown a photograph of the crime scene, the young woman’s bedroom. He said he killed her. Next, he was shown a group photograph of the victim with her parents and three sisters. He correctly identified the victim in the photograph. It was a convincing demonstration, but other factors caused the investigator to doubt Lucas’ confession. Subsequently, Lucas admitted that he had faked the confession. How was he able to pick the victim out of a group photograph? He picked the one wearing glasses. How did he know the victim wore glasses? In the crime scene he was shown initially, there was a pair of glasses on the nightstand beside the bed.

Lucas grew up hard in Virginia. His life as an adult was spent in prisons, rescue missions, flophouses and, occasionally, as the unwanted guest of relatives. He worked sporadically at menial, low-paying jobs and scuffled in the streets for bits of scrap to peddle for pennies. He was not a drifter, but a scavenging forager, content to stay put until the territory was picked clean. He remained with his wife in Maryland until she drove him away. He migrated to Florida and remained there, living with Ottis Toole’s family, until the authorities compelled him to leave with threats of taking his 15-year old girlfriend away from him. He fled to California and lived with his employer until the employer put him on a bus to Texas. He remained in Texas, courtesv of a relieious commune in Montague County, until his arrest.

In Lucas, there was none of the compulsive behavior that Cuba and Norris identify as characteristic of the serial killer. He was compelled to do nothing but survive.

SURVIVAL IN THE primitive world that Lucas knew is not simple. One must acquire complex animal wits and cunning. Like the gambler of popular song, Lucas spent a life “reading people’s faces, knowing what their cards were by the way they held their eyes.” Tape recordings of many of his confessions show that Lucas was able to discern details of crimes from innocuous questions and revise details if he sensed he was not telling investigators what they wanted to hear.

Because researchers such as Cuba and Norris persist in trying to explain Lucas as a serial killer, the mystery of Lucas remains intact. Beyond that is the larger mystery of how so many smart cops could have been taken for such a long, ignoble ride, and why the public would believe his fantasy long after it had reached incredible dimensions.

Shown proof that Lucas was in Jacksonville, Florida, on the days when he was supposed to have committed three murders in Baytown, Texas, the Baytown police chief accused Lucas of inventing the alibis-official government documents and private business records-and refused to reopen the cases. A California television reporter refused to believe that Lucas had not killed two young girls there, although records showed he was selling scrap metal in Florida about the time they were killed. To cling to that belief, the reporter came up with a rather comic rationale: “Maybe he had a business agent who sold the scrap for him.”

To believe that Lucas was the serial killer he claimed to be, the authorities and the public had to believe that he falsified his prison release date and years of work records; that he falsified food stamp applications, blood bank donations, traffic tickets. Such a feat would require one hell of a business agent.

Sadly, the entire Lucas saga may speak less of his brain damage than of the peculiar mentality of those who have attempted to confront him. Cuba and Norris point to his “hyperreligiosity” as a symptom of “possible temporal lobe epilepsy.” Is there not a hyperreligiosity that demands that if men are to believe in the Ultimate Good, they must also believe in the Ultimate Evil? If Lucas invented death cults and gods who spoke to him in the night, we invented something just as large. We invented Henry Lee Lucas, Lucifer incarnate, and even now, in spite of all we know, there are those among us who cannot admit that he doesn’t exist after all.

Related Articles

D CEO Events

Get Tickets Now: D CEO’s 2024 Women’s Leadership Symposium “Redefining Ambition”

The symposium, which will take place on June 13, will tackle how ambition takes various forms and paths for women leaders. Tickets are on sale now.

By D CEO Staff

Basketball

Watch Out, People. The Wings Had a Great Draft.

Rookie Jacy Sheldon will D up on Caitlin Clark in the team's one preseason game in Arlington.

By Dorothy Gentry

Local News

Leading Off (4/18/24)

Your Thursday Leading Off is tardy to the party, thanks to some technical difficulties.