Jack Schoop’s head is full of empty space. Of plazas, water fountains, grass and trees. Of office workers eating their lunches in vest-pocket parks, or strolling over to the city museum for half an hour’s worth of impressionism. It’s a city planner’s dream, and Schoop is Dallas’ chief city planner.

George Charlton’s head is full of the C坢zannes, Monets and Mondrians that will be added to the collection of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, whose board he chairs, when it opens its new facility at Harwooa ana fiora streets in the fall of 1983. And of the crowds of people, perhaps a million a year, who will visit the 200,000-square-foot, $40-million building.

Leonard Stone, meanwhile, is thinking about bonds – the municipal bonds necessary before the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, for which he is executive director, can begin building its new concert hall at Pearl and Flora, two blocks east of the museum. If the bonds are approved this August, he can dream of the 1986 opening when 2,200 patrons will, with luck, be awed by the world-class acoustics of the orchestra’s new home.

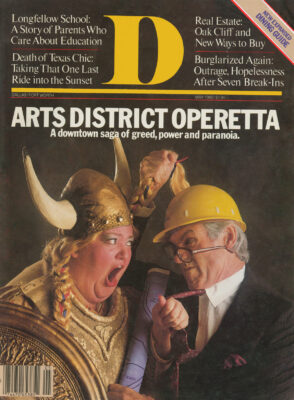

Just about everyone involved with the city’s emerging arts district is mentally balancing dreams and dollar signs nowadays. The 60-acre district could be a unified combination – virtually unique in the world – of cultural facilities, parks and sensitive commercial development. Without succumbing to institutional sterility, it could include a dazzling museum, I.M. Pei’s spectacular concert hall, an arts school and perhaps a theater. Without being dominated by business behemoths, it could contain up to 15 million square feet of commercial development, valued at more than $1.5 billion.

The museum will almost triple its exhibit space and more than double the value of its collections (currently about $25 million), thanks to donations from three private collectors in recognition of the new facility. The symphony would almost double the number of performances it can give in a year; luck and the talents of acoustician Russell Johnson allowing, it could have one of the few musically satisfying symphony halls to be constructed in the past quarter of a century.

And civic boosters could have a major asset with which to lure corporate relocations, while builders interested in downtown residential construction would have a major incentive to offer potential buyers. Even mass transit could get a boost, since evening riders to and from cultural events would help defray the costs of whatever system eventually is constructed.

“Our city has the chance to build something that will give us character, a world character of fine quality,” says Harlan Crow, one of six private developers owning land in the district. “Most major cities have something special that’s desirable. Dallas really lacks that, and here’s our chance to make something.”

Sounds great, doesn’t it? It makes you wonder why, almost five years after the idea first came up, we still don’t have an arts district. Because, although things are moving right along (finally), there are still plenty of ifs. If the bond issue passes. If the symphony can raise enough private money ($17 million to $19 million) to meet its 40 percent share of a construction tab that could reach $48 million. If the city, the arts groups and the private land owners continue working together. If the private owners are willing – or able – to bear much of the cost of creating the district. If someone doesn’t just get mad as hell and ruin the whole deal.

“I saw Harry Parker, the museum director, over at the museum the other night,” Harlan Crow says. “Harry asked me how I felt about Flora Street, and I said, ’Harry, with all the goddamn adverse publicity we’ve gotten, I’m frankly losing interest.’ “

A BRIEF HISTORY lesson: The museum’s board of directors started the arts district in the spring of 1976, though the members didn’t know it at the time. The board, aware that the museum was bursting the seams of its 64,000-square-foot exhibit hall in Fair Park -and missing out on many patrons who would visit a more convenient location – considered appointing a study committee for a new museum site. Margaret McDermott, who at the time was chairman of the museum’s board of trustees, was “the big force behind the new museum,” says current board chairman George Charlton. “She believed in it before anyone else thought it could be done,” agrees board president Irvin Levy. She eventually gave the largest single contribution to the museum’s construction fund.

Prodded by her enthusiasm, the board established the study committee. Charl-ton, son-in-law of former Dallas mayor Erik Jonsson, was named chairman. He spent months speaking with civic leaders and “city fathers” – translation: rich civic leaders – to “see if the project was feasible.” He figured it would take $12 to $15 million in private contributions to pull the project off (eventually the museum raised about $20 million). “The general consensus was that this was an immense amount of money, the largest amount that had ever been raised before in Dallas, but that the situation was not hopeless, Charlton recalls.

Indeed, Charlton got some very good news. If the new museum were built, it would be given the collections of Dallas’ three premier art collectors. Al Meadows’ broad-ranging pre-impressionist to contemporary collection; Lillian and Jim Clark’s magnificent collection of Mon-drian, perhaps the world’s best; Margaret McDermott’s impressionist collection -all would become the property of the museum. Their total cash value was approximately $25 million, but their significance outweighed their worth. They were a token of trust in the museum, a sign that with its new facility, it would have arrived. They also were a heavy inducement for potential givers. By the fall of 1976, Charlton’s group was looking for sites.

Bob Kilcullen, a real estate broker and museum lover, found one. He called Clark and John Murchison, the chairman of the museum board, and asked them to look at an 8-acre site on Harwood Street between Ross Avenue and the Woodall Rodgers Freeway. One cold, wet October morning, they looked at the site and liked it. It was cheap, at $8 to $25 a foot; it had great access to downtown, North Dallas and Oak Lawn; it was surrounded by other developable space, on which a symphony hall or park could be built; and nobody else wanted any of it. Kilcullen started asking property owners if they wanted to sell.

By May of 1977, he had secured free options to buy 40 percent of the land the museum needed, plus acreage nearby. And the museum’s architect selection committee, chaired by Charlton, had picked New York architect Edward L. Barnes to design the new museum. Barnes liked Kilcullen’s site, as did the consultants at Carr, Lynch Associates, which the city had hired to make recommendations on how to help local arts groups.

The museum started the arts district concept, but Carr, Lynch fleshed it out. The research team found that the museum’s exhibit area needed to be tripled, that the Fair Park fine arts building was “not equipped to protect valuable works of art” and that the park was a poor location for a facility whose patrons came primarily from North Dallas. The symphony and Dallas Opera, meanwhile, lacked rehearsal space and performance time at the Music Hall. Even when they could schedule performances there, they were hindered by the hall’s mediocre acoustics.

The museum, the opera, the symphony and the Dallas Ballet all were site-hunting, and the consultants thought they might as well move into the same neighborhood, surround themselves with parks and plazas – and a bit of commercial development – and become an arts district. Their study, released in October 1977, recommended that the district be in the northeast corner of the Central Business District.

By June of 1978, city leaders and the museum backers were ready to go. The new museum building was planned, $12.5 million in private contributions was in hand, and the city had allocated the museum $28.7 million from its upcoming bond issue, set for June 10. Indeed, the city was backing every major arts group in town for bond money. The symphony was to get $18.9 million for construction of a new hall; the Dallas Theater Center was up for $9.2 million in expansion funds; the Majestic Theatre was up for $4 million in renovation money; the opera house was to get $3.6 million for a new site; another $3 million was earmarked for “supporting facilities.” It was a gesture in the grand Texas tradition. The city was trying to build the arts district in one fell swoop, at a total cost of $45 million.

“1 don’t think we’d lost a bond issue in Dallas in the last 10 years,” Charlton recalls. So campaign advisors did not heed warnings about offering taxpayers more than they could swallow. Nor did they alter the time-honored tradition of keeping quiet about bond issues, in hopes that only supporters would bother to vote.

One week before the election, Califor-nians passed Proposition 13, which gave Charlton a very bad feeling in the pit of his stomach. His stomach was right. Less than 16 percent of all registered voters cast ballots, but this time it was the antis who showed up. While 58.6 percent of the voters approved Erik Jonsson’s cherished downtown library, only 45.6 percent affirmed the cultural bond issues. The museum lost all its land options.

George Charlton and his colleagues conferred the morning after that defeat and decided they had not yet begun to fight. They asked Kilcullen to get new purchase options, and Kilcullen started knocking on doors. Even so, he was almost too late.

When Kilcullen went back out to the landowners, he found that they wanted the museum to pay for its options this time. And the purchase price on some parcels had doubled. The arts district idea made owners think their land might be worth something. One owner, holding title to the property at Ross, Harwood and Olive, wouldn’t consider an option. He wanted to sell his property outright, but the museum didn’t have the money to buy it.

Trammell Crow had the money, and he bought the land. He bought it, in fact, within three weeks of the bond issue’s failure. He liked it for the same reasons the museum backers did: It was cheap, close to several major traffic arteries and within a few blocks of downtown. “It was a good area to develop, and we could develop a large project,” Crow says. He felt the same way about the east end of the arts district, which is defined by Routh, Ross, Central Expressway and Woodall Rodgers Freeway. “I guess I started buying land there back in 1976,” he recalls.

Crow was the first developer to buy into the proposed arts district, and the 90,000 square feet he purchased in the summer of 1978 for about $20 a square foot was worth $125 a square foot within three years. It was, in other words, a shrewd buy.

The arts patrons did not call Crow shrewd, however. They called him menacing, self-interested. A threat to the environment of the museum. A trespasser upon the arts district. In the name of beauty and culture, they asked him to sell them back the property.

In the name of free enterprise and economic health – of the city, not only of Trammell Crow – he refused. The Central Business District was moving in that direction, he told them, and parks or plazas would impede its natural growth. The land was perfect for a high-rise development, and it would be best for all concerned if he held on to the property. Which he did, producing a bitterness that some arts patrons still taste when they speak of him. Indeed, that conflict – perhaps inevitable given the ambition and farsightedness of the two camps and the desirability of the property – has affected Crow’s relationships with the various arts groups ever since.

As far as the development of the arts district was concerned however, the dispute with Crow was more a symptom than a disease. The Central Business District’s growth, and to a lesser extent the very notion of an arts district, pushed property values ever higher. Available land was rapidly blocked up by brokers and sold to commercial developers, who saw the same virtues that Crow had, albeit later in the game. “What attracted us was really the prospect of an arts district,” says Webb Wallace, local partner in the Tishman Realty Corp., which bought into the district last spring. “With the district, there was a prospect for superlative development. Without the district there was the prospect for a piece of still promising downtown property. It would be a good deal one way, and a great deal the other.”

It was sort of a raw deal for the arts institutions, who, with the exception of the museum, were priced out of the game. The museum won $24.8 million for its project in a city bond election held November 6, 1979. Thanks to Kilcullen, it still had options on land for $13 to $25 a square foot. The symphony was allotted $2.25 million in bond funds for site acquisition, but it had no options. By June of last year the symphony association had to throw up its hands and announce that it simply could not afford to buy “arts district” property. And the opera, which was not on the 1979 bond issue -it wasn’t ready to proceed and did not want to clutter up the ballot and endanger its sister institutions-seemed to be out of the picture entirely.

Obviously, those economic facts changed the very idea of the arts district. The Carr, Lynch concept was of a square, compact collection of cultural facilities and parks, with commercial uses accounting for about 16 percent of the district’s land area. In the current district, the commercial ownership accounts for about 65 percent of the land. The current district stretches rectangularly from St. Paul’ Street east at least to Routh Street and possibly to Central Expressway.

In retrospect, the changes nave not been for the worst. Dr. Philip O’Bryan Montgomery Jr., who is coordinating work on the district, says the new layout “is better, because it’s bigger. You have a much bigger area along Flora Street than you did before, and you can put more on it.”

With the private developers involved, there would be more money to spread around on the special landscaping and building designs the arts groups have envisioned. “The Carr, Lynch recommendations probably were a purist ideal or vision,” says Vic Suhm, the assistant Dallas city manager who has helped coordinate arts district activities for the city. “The reality is that the arts institutions have to have the funding and planning, and you are dealing with privately owned land that has high value, and you can’t just confiscate that.”

That is one reality. Another, brought home by the symphony’s problems last summer, was that there might not be enough “art” in the area to form a cohesive district. “You couldn’t have an arts district with just the museum,” Wallace says. Something had to be done about the symphony.

IT WASN’T THAT THE SYMPHONY DIDN’T know what it wanted. A committee chaired by Mrs. Eugene Jericho had worked on that question for 18 months and had decided that the best site was a chunk of land at Pearl and Flora street, next door to the Borden plant. “We had anticipated costs of $15 to $20 a square foot in 1978, and by 1981 was going for in excess of $115 a square foot,” Leonard Stone recalls. The symphony needed 50,000 square feet for the concert hall alone, and the city wanted green space, parks and plazas around the building. But its $2.25 million would buy only half enough land for the building. “Given what the market was asking for land, and what the bond issue had provided us, we ultimately had no option at all,” Stone says.

“On the sixteenth of June we told [Mayor] Jack Evans that we were convinced we would never get an opportunity to get into the arts district. He said, ’1 will take it upon myself to try to find you space.’ “

Evans knew the symphony wanted some of Borden’s land. He also knew Eugene Sullivan, the chief operating officer of Borden. The two had met about four years earlier at a grocery industry convention, which Evans attended on behalf of Tom Thumb grocery stores. “When 1 called him, he was in an executive committee meeting and he stepped out of the meeting and talked to me on the phone,” Evans says. “I explained what we needed, and he said he would get right on it. And boy, he did.”

Within two weeks, Sullivan had flown down from New York and taken an automobile tour of the arts district. All the city needed from Borden, Evans explained, was about 25,000 square feet of land (then worth more than $2.5 million). The city owned adjacent land, and could buy out five smaller landowners. “He said they did want to relocate their plant and 1 said, ’We would like to help you stay in Dallas.’ And the more we talked, the more he became interested in what they could do about a gift,” Evans says. “He said, ’Let me run it by my board,’ and two weeks later he called and said, ’We want to give you those 25,000 feet.’”On September 18, 1981, the gift was announced.

What was not made public at the time was the involvement of Tishman, which had been negotiating to buy the rest of Borden’s property, next door to the symphony site. “Tishman was involved in the donation package; they were part of the negotiations,” says city planner Schoop. While the symphony deal was strictly between Borden and the city, there was a sweetener for Tishman (a sweetener that, presumably, helped Borden to charge Tishman a healthy price on its remaining acreage.) “There was a promise that the city would be building some parking spaces that could be used by Tishman while they were building their own space,” Schoop says. “About 2,000 spaces, which was about what we needed for the symphony anyway, and for public uses down there. So that was no big problem to us.” There were reports at the time that the city had given Tishman something for free. Webb Wallace dismisses those stories as “newspaper talk.”

Trammell Crow also offered to help the symphony, Evans says. “1 went over to speak with Trammell and Lucy [Billingsley, his daughter], and they were very generous… They were going to sell their land [at a reduced rate]. But his site didn’t fit the symphony as well as Borden’s, and I told him, ’If we get this offer from Borden, it’s better.’”

While Evans was out beating the bushes for land, the symphony was not sitting idle. (Indeed, it had been speaking with lower-level Borden officials for months about the land, without success. “Sometimes people at top levels move faster and people at lower levels are more cautious,” says a Borden spokesman.) Since November 1979 the symphony association had had a committee headed by EDS President Morton Meyerson investigating what sort of hall should be built, and who should build it. In January 1981, I.M. Pei was notified that he had been selected from among 100 prospective architects. “I knew that I.M. was going to get the commission when he said, ’I’ve never designed a concert hall in my life, but before I die I must design a great one,’ ” Stone recalls.

Equally important was the acoustician, the sound expert who is to tell Pei which sizes, dimensions and building materials make for the best concert sound. The symphony gave that job to New Yorker Russell Johnson in February 1981, Stone says. Not many concert halls are designed in any given year. Johnson has designed them in Manila; Winnipeg; Hamilton, Ontario; Montreal; and Minneapolis-St. Paul.

The symphony site still needs some additional 44,000 square feet of land – which the city is acquiring -but when the mayor and Borden came to an agreement, the biggest threat to the arts district was resolved. It looked like everything was ready to go.

THE QUESTION WAS, go where?

Before Borden’s donation, there had been no certainty of an arts district ever coining about. Consequently, there had been little unified planning. Even after the Borden gift, it took a month to set up a meeting of all the developers involved in the district. It took another four months to get a coordinator to work with all those developers, plus the symphony, the museum and the city.

Several land-owners had development plans before September, Schoop says, “but they were all just for big buildings and big parking garages. We told them, ’Look, everyone else is building huge buildings too, and if this keeps up, there won’t be an arts district.’ “

Nick DiGiuseppe, one of three principals in the Triland partnership, says that the first meeting occurred in October. “Everyone was kind of approaching it skeptically. They would say, ’I’m here to observe, but I’m going to reserve my judgment until I can see what’s going on.’ Everyone said it was a good idea, it would be good for the city and for us.”

At the second meeting, in November, the group began talking about concepts – about making Flora Street, which connects the museum and the symphony on an east-west axis, into a special area with low store and restaurant fronts, parks and fountains and coordinating building designs. DiGiuseppe and his partners started dreaming up creative ways to use the land in the district – their own and everyone elses. In a way, they had to. Their properties, which they bought last spring, are relatively small; one sits at the crucial corner of Flora and Olive, right between thv museum and the proposed conceit hall. “Their individual properties were basically worthless without an overall plan,” says Michael Young, another developer in the .district.

At any rate, by the group’s third meeting in January, the Triland staff-alarmed at what seemed to be an aimlessness to some of the two-hour sessions – prepared some overall concepts, including one that Schoop has adopted as a key to the health of the district. Triland proposed a 12,000-car garage for the area, to be buried underground. It would be aesthetically pleasing, it would allow better use of the above-ground land that otherwise would have to be devoted to parking decks, and it would be extremely expensive. About $10,000 a stall, say. Or $120 million. The city and John DeShazo, a private traffic engineer, are studying the matter.

The confusion that worried Triland was probably only natural. Nothing like the Dallas arts district has been done in North America. Among the participants here, the balance of power was feather-sensitive – the city could not pass terribly stringent land-use laws for fear of a lawsuit, and the developers could not ignore the city for fear of terribly stringent land-use laws. The arts groups are run by some of the city’s most powerful citizens, but they have direct control over only the land that they own. Everything depended on amicable cooperation, which meant that not much could be accomplished. No one could assert strong leadership, due to a planning phenomenon known as “paranoia.”

If an arts group or private firm tried to take charge, it would be accused of conflict of interest. If the city tried, it would be accused of acting dictatorial. “We would have been eaten alive,” Schoop says. Instead of calling in an outside moderator, the group tried to run things by committee.

“At first, everyone thought that maybe the group could just work with each other,” Schoop says. “That would have been ideal. You had some of the greatest architectural minds in the country working on these projects, and if they had been able to work together, you wouldn’t have needed someone to mediate.”

By the January meeting, however, it was clear that someone had to be in charge. The group agreed that Bryghte God bold, a private citizen who helped usher Dallas’ sign ordinance into law nine years ago, would be a likely prospect.

Godbold, says DiGiuseppe, spoke to the group in late January and pretty much scared the heck out of everyone. “He was talking about getting this [district] legislated into place,” DiGiuseppe says. “He wasn’t given that mandate, and I guess that’s why he’s not fulfilling that role.”

The man who finally took the unpaid mediator’s job is Philip Montgomery, a medical doctor, professor of pathology and associate dean at the University of Texas at Dallas Health Science Center. Dr. Montgomery has, sort of as a hobby, supervised the construction of $200 million worth of university facilities on four different campuses. He may be the university system’s chief expert on development and construction. And he loves his work. “It’s a huge opportunity for the city, and it’s a great opportunity for me,” he says.

Once Montgomery came on board, things took off. Within a month the group was approving guidelines for a competition to be held for a “master planner” who would help decide on key features of the arts district -an idea the members earlier had rejected. The competition began on March 26, when 14 of the nation’s more prominent architects and urban planners traveled to Dallas to hear the basic rules for the arts district.

THE GENERAL DESIGN concepts on which the eventual final plans are to be based have been agreed to by the public and private developers at work in the district. They include:

-Establishing Flora Street, which bisects the district from Harwood to Routh,as a ceremonial boulevard with specialgreen spaces, building setbacks and,perhaps, height limitations on nearbystructures – especially those within 100feet of the curb. Pedestrian traffic is to beemphasized more than automobile travel.

Providing public spaces where artistscan display and create works of art.

Providing enough outdoor space,perhaps through an amphitheater, toallow for outdoor plays, concerts anddance festivals.

Assuring that the ground floor spacein buildings is devoted to retail stores,restaurants and bazaars, using designsthat tie those facilities directly to the outdoor plazas and street fronts.

– Making the entire district comfortable for pedestrians – physically and psychologically – by using landscaping, water displays, street furniture and plazas, and by minimizing the troubles caused by sun and wind (no reflective glass buildings, for instance).

The timetable for much of the planning also has been set. By mid-May, the design contestants should have their drawings in. Approximately 10 of the original 14 are expected to make submissions. By month’s end the master planner should be selected by the various arts district interests. By mid-June a decision should be made on whether the district can benefit from a mega-garage such as Triland has suggested. By mid-August the design of Flora should be complete. And by June, individual developers should have enough information to begin serious design work on their projects.

Meanwhile, the symphony association has its own timetable of preparations for the crucial August 3 vote on construction funds for the Concert Hall. l.M. Pei’s design has been transformed into a scale model that, as of early April, was still a deep, dark secret – to all but the symphony’s biggest potential contributors. “It can get people to feel that they are kind of special, and they are getting a special look, and therefore they should give a special contribution,” Galland explains. Philip Montgomery’s son, also named Philip, is in charge of the public relations campaign for the bond issue and is not taking passage for granted; the symphony will run a full-fledged political campaign this summer, as it should have in 1978. It would seem crazy for the voters to reject construction funds after approving the arts district in the 1979 referendum, but stranger things have happened.

While the symphony bites its nails, the Dallas Opera is mostly a spectator this year. It needs a bigger stage than the Music Hall can provide, but the symphony’s departure from Fair Park would, at least, ease its scheduling problems. It has not begun fund-raising for a new site, and Lucy Billingsley says that if the city wants to put an opera house on her land at Routh and Flora, it should plan on buying the property from her.

The private developers, meanwhile, are re-evaluating their previous plans, trying to cope with the aesthetic demands of the arts district and the economic realities of downtown development – which seems to be entering a slow-down that could last two to four years, by some estimates.

Several of the owners don’t yet know ex-actly what land they eventually will develop. Tishman and the city are in the midst of appraisals comparing Tishman’s property near the symphony- which needs an extra acre to accommodate Pei’s grand plaza -with the city’s land at Har-wood and Woodall Rodgers. When the appraisals are complete, Tishman will swap some of its land for some or all of the city’s on a dollar-for-dollar basis. Tishman and Triland are talking about swaps or joint ventures, also, since each will end up with property virtually in the middle of the other’s.

A FEW of the potential quagmires appear more treacherous than the land swaps, which really depend only on mathematics. The underground parking garage, for instance, is a technical challenge that would solve a lot of problems if it can be built. It would save the view, save space and save money since nighttime and daytime activities would use the same lot, reducing the overall need for parking. “It’s really critical in my view,” Schoop says. “Without it, we won’t even have a district. It’ll just be cars and garages all over the place.”

Then there’s the matter of whether Lucy Billingsley’s 9.5 acres east of Routh – and, of course, the land of the smaller property holders who are her neighbors -should be in the district. In March Ms. Billingsley balked at joining the district before knowing what restrictions might be imposed on property within its boundaries. After someone leaked an internal memorandum criticizing her father, Trammell Crow, the city sidestepped the question by saying that the master plan should determine what property the arts district needs. Most of Ms. Billingsley’s fellow developers say they do not think that her property is cru cial to the success of the district; the rib planning staff evidently thought that i was. What if the master planner agree with the city?

There could be a revolt. If not by Ms. Billingsley, then by citizens such as John Leedom, a state senator and former City Council member who manages almost two acres of land at Ross and Central Expressway. “This is about as near to the arts district as RepublicBank,” Leedom says. “We aren’t interested in being in the arts district, and hopefully won’t be.” And, he adds, the city should walk softly when it “starts talking about great plans with other people’s money.”

Leedom even worries that the park areas of the district could become a problem in their own right. “One of the sad things about my tenure on the council was the number of people wanting us to close some of these little neighborhood parks, because of the effect they were having on the peace and tranquility of the neighborhoods,” he says.

Harlan Crow worries about height restrictions; Webb Wallace says the issue of whether Flora Street should be pedestrian, automobile-oriented, or both, may “seem like a big issue,” but probably won’t be.

And there is the question of the delicate personal relationships among everyone involved in the planning process. The flap over criticisms made of Trammell Crow by Schoop and Assistant City Manager Vic Suhm briefly paralyzed the negotiations. Harlan Crow says he likes the two memo-writers, and blames the Dallas Times Herald for the disturbance, saying “journalism is too good a word for that stuff.” But his father says, “I have no grudges against the Times Herald. The Times Herald was just doing its job, printing the news.” Trammell Crow says he is upset with Suhm. Schoop says, “1 think we’re holding together pretty well.” His boss, city manager Charles Anderson, says, “1 see the issue as being resolved. 1 don’t see a feud.”

Leonard Stone, speaking from the symphony’s perspective, feels that none of the disputes so far are anything to be alarmed about. “This is a daring plan,” he says. “Few cities in the world have had the ability or the desire to stake out an area of downtown that is growing as vitally as Dallas and to dedicate it to the arts. And what is happening now should be happening now. The disputes are coming out. This is when it should be happening. This is the planning stage. So while the reading public may view it as dissension, I view it as absolutely necessary.”

Stone has a vested interest in optimism, but he also has a point. The developers, the city and the arts institutions agree on most of the important issues. Each of the private landowners already has voiced strong agreement with the general arts district concept, and each has agreed to donate $20,000 to the planning process.

Each also has announced a willingness to sacrifice some building size in order to create an eye-pleasing district. Harlan Crow plans to use only one-third of his 90,000-square-foot lot across from the museum for construction. The rest, he says, will be used for “a park, a plaza, whatever is suitable.” On the other side of Flora opposite the museum, the joint venture of Luedtke, Aldridge, Pendleton and the Young-Gentek Company is planning to build an office building of 650,000 square feet, at most. Under the city’s zoning laws, they could build up to 840,000 square feet. “Everyone is expecting to give a little,” says Webb Wallace of Tishman.

He thinks the interests of all parties in the project are so similar that any problems are bound to be solved. “I do not think that there is a conflict between a good arts district and what will make the developers happy,” he says. “Everyone wants an exciting district… we want Flora to be something special that will attract the kind of activity that the district needs.”

“Everyone wants the district to happen.Everyone realizes that it’s best for us individually, it’s best for the city, it’s best forthe populace if there is an arts district. Ifthere is to be an arts district, everyone willhave to give a little to make it.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain