Fox & Jacobs sells houses the way Procter and Gamble sells detergent. And as a result, it sells more of them than anybody else.

On a typical Sunday afternoon, from The Colony in the north to The Woods in the south, from Rowlett to Fort Worth, some 1500 people will troop through Flairs, Accents, Todays. In fully furnished model houses, they will admire the Garden Kitchen, the 100-percent nylon short-shag carpet, the oak frame cabinets and polystyrene drawers and one-piece “molded marble” vanity tops.

By the end of the day, a hundred of them will have decided to buy Fox & Jacobs houses.

From its founding in 1947 through the end of last year, Fox & Jacobs sold 24,171 new houses. Twenty-two percent of those sales, 5,236 houses, were made last year – an average of 100 a week.

Last year, in the Dallas area, there were 15,000 new home starts. A third of them were Fox & Jacobs houses. But more than half of the houses started in Dallas last year were priced over $50,000. Fox & Jacobs didn’t build any houses to sell for more than $50,000 last year, so its share of the market it serves is close to 65 percent. There are bigger homebuilding companies, but none of them has a market so thoroughly sewn up as F&J does. U.S. Homes, for example, builds coast to coast, but not in Dallas, largely because F&J is such a formidable competitor.

Fox & Jacobs has no intention of cutting back, either. With the initiation of the project to build houses in East Dallas, just a few blocks from downtown, F&J struck out in a direction that clearly indicates its desire to seek out buyers other than middle-income suburbanites. As Bob Harper, director of sales and marketing for Fox & Jacobs says, whimsically but with an eager undertone, “We’d love to be sued as a monopoly by the Federal Trade Commission.”

If that ever happens, it will be because F&J knows how to dominate a market.

“If we built the Taj Mahal and put it on sale for $1500,” Bob Harper says, “some people wouldn’t want to buy it because it was a Fox & Jacobs.” Harper isn’t complaining; he’s commenting realistically about the image Fox & Jacobs has created for itself. General Motors doesn’t try to sell Chevrolets to corporate executives. That’s what it has Cadillacs for. Fox & Jacobs aims its Today and Accent lines at the Chevrolet market: 24 to 35 years old, with a combined family income of $16-20,000. Its secondary market, roughly equivalent to Buick’s, is 35 to 44, with a family income in the $20-25,000 range. For those buyers, F&J builds Flairs and souped-up Accents.

The design of the houses is the product of careful market research. Although much of the research takes place on Sunday afternoons at the model homes – Bob Harper says that after 30 minutes of eavesdropping on people going through a house, he knows whether he has a seller or not – F&J also relies on more sophisticated techniques, such as national opinion surveys conducted by Daniel Yankelovich, Inc., to pry into every aspect of American values that can be reduced to statistical data. Much research specifically tailored to Fox & Jacobs’ needs is administered by the Bloom Agency.

The uniqueness of Fox & Jacobs, according to Bob Bloom, is its commitment to “packaged goods disciplines.” Bloom clients like Pet Incorporated and Anderson Clayton Foods rely on these disciplines, as one might expect of manufacturers of evaporated milk and salad dressing. But for a homebuilder to use them is extraordinary.

Like Chiffon margarine or Pet milk, a Fox & Jacobs house is sold by its brand name. Since for most people Flair is a felt-tip pen, Accent a meat tenderizer, and Today an early morning talk show, the most important brand name is Fox & Jacobs itself. No homebuilder has a stronger name identification. Say “Centennial” to the man on the street and he’ll identify it as a liquor store. Say “Raldon” and he’ll ask you to spell it. But say “Fox & Jacobs” and 82 percent of the people you play this game with will say, “They build houses.” In fact, 52 percent of the people will say “Fox & Jacobs” if you ask them to name someone who builds houses in Dallas.

The corporate identity is visible on everything from billboards to prime-time TV commercials to schoolbook covers imprinted with the company logo, a stylized F and J linked in a shape that suggests a leaf. Other builders christen their subdivisions. But once Timbertree Acres or Thrushcross Grange is sold out, the name disappears and with it the identity of the builder. The F&J lines have a permanent identity: Real estate agents like to use the brand names in their newspaper classifieds whenever a Flair or Accent or Today goes up for resale.

Bloom is currently supervising a “benefits and promises” study to discover how much credibility F&J advertising has, as well as to single out which features of F&J houses are essential and why. Since F&J aims at “the most house for the money,” Bob Harper explains, it has to be conscious of what people really want as opposed to what they’d like to have but are willing to give up. Currently, for the market F&J serves, the good life consists of having two cars, making an annual trip to Aspen or Mazatlan, and keeping up with the Joneses if the Joneses suddenly turn up with a Betamax or a redwood hot tub. So to keep the house payments on a Flair at a level that will allow its customers that little bit of extra cash to put on the Winnebago or the Master Charge bill, F&J chooses not to provide them with built-in microwave ovens or wood shingle roofs.

To figure out what the current essentials are, F&J polls 200 couples in the 24-to-35, $15-to-$25,000 range and asks them why they want certain things. Everyone wants a two-car garage, for example; but do they want it for extra storage, workshop space, or the security of locking up two cars at night? The response, if there is a significant trend in any one direction, could significantly affect the size, shape, and amenities of future F&J garages. Would you rather have a wet bar in the dining room or a half bath for your guests? Built-in bookshelves or a bigger master bedroom? In a Fox & Jacobs house you can’t have it all, and determining that delicate balance of desirable features is not easy.

These “psychographics” enable F&J to pull in its share of the mainstream, middle income, mid-American homebuyer. “Our product,” says Bob Harper, “is the American dream in the suburbs: a little plot of ground, apple pie, kids in school, PTA.” But that dream changes color every few years. The most dramatic change has been in the size of the family (Fox & Jacobs calls it the “buying unit”). The average “buying unit” is now 2.5 people, meaning that more and more buyers in the Fox & Jacobs market have no children.

The F&J customer is not the first by whom the new is tried, though he may be the last to lay the old aside. Still, the company has to monitor changes in taste and style so its model homes can exert their allure. “What you want to do is project warmth, friendliness, and luxury – but not too luxurious – something your prospect can identify with,” Harper says. In the early Seventies, the decor of the model houses was influenced by the “go-go” look of the psychedelic Sixties, Harper says. Rooms were filled with bright oranges, yellows, and greens, “Spanish-style” furniture with baroque curlicues, and lots of chrome and glass. Then came the recession and energy crisis of the mid-Seventies, and people scrambled for security. “Earth tones” – homey beiges and browns – came in, as did front porches, columns, shutters, suggestions of grandmother’s house. Designers had to carve out space for dining rooms.

Now, Harper says, brighter colors are back, and the eclectic look is filtering in. People are buying a look that’s “contemporary but solid” – sloped ceilings with wood beams, paneling that mixes mirrors with rough-textured wood. In short, any look that House and Garden said was new last year, the Fox & Jacobs customer is probably beginning to feel comfortable with now. The conservatism of Fox & Jacobs customers probably also stems from the fact that most of them give “investment” as their major reason for buying a house. Personally, the buyer might want purple carpet and wallpaper with big pink roses, but he’ll choose beige and off-white because he has resale value to contend with.

If a Fox & Jacobs house looks boringly conventional to some people, that’s the point. “We can’t be all things to all people,” Bob Harper says. “There are people willing to pay a price for individuality. They won’t buy a Fox & Jacobs house.” But he adds: “We want to sell to everybody. Someday we will.”

That broadening of the market is apparently what lies ahead for Fox & Jacobs. Already the company has moved into Houston, where it is building for the same sort of market it serves in Dallas and Fort Worth. And in the imminent East Dallas project, usually called the “in-town” project, the company is seeking a new segment of the market in its hometown.

Fox & Jacobs’ success is usually attributed to the skill and charisma of its president, Dave Fox. “Dave Fox is brilliant,” says Bob Bloom. “He’s gutsy, with a rare combination of shrewdness and intuition. He understands marketing as few people do. There aren’t five home-builders in the United States who have a marketing plan. Dave is very disciplined. He’s an imaginative pragmatist. He’s maybe the most respected man in home-building. They call him ’Mr. Marketing.’ ” But Dave Fox will be the first to admit that the techniques that have made F&J a success were evolved through a process of trial and error. And, for a long time, mostly error.

When World War II ended, Ike Jacobs came home to Dallas with big plans: he was going to make a killing in homebuilding. Not that he knew anything about homebuilding, but with a degree in mechanical engineering from A&M and a more-than-average amount of drive, he was sure he could do it.

Ike was born in Navasota, Texas, in 1919, but he grew up on the streets of South Dallas. His parents, Julius and Sarah Jacobs, ran a small dry-goods store on Second Avenue, a tough neighborhood that was gradually being deserted by the Jewish families that had settled there at the turn of the century.

When the Jacobses opened a second store on Knox Street in 1928 and moved into a house on Abbott, there were some transitional difficulties. For one thing, Ike was a fighter. The principal of Armstrong School made a call on Mrs. Jacobs to remind her that Highland Park children were not used to roughnecks like Ike. She promised to keep him in line. When a class bully finally tested Ike’s patience to the breaking point, she allowed him one fight – off the school grounds. So after school, Ike and his adversary crossed St. John’s, and on the creekbank across from Armstrong they slugged it out with the whole school watching. Ike won, and he never had to fight again.

He remained a mixture of daredevil and stoic. At seven, he was struck by a line drive in a softball game but shrugged off the pain. Three weeks later, when the family doctor came to treat Mrs. Jacobs for the flu, he clapped the boy on the shoulder and was startled by a gasp of pain. Ike’s collarbone had been broken by the softball, but he had concealed the injury.

Reckless, aggressive, and competitive, he would ride his bike on a dare down the steep, chalky Turtle Creek embankment near the Highland Park tennis courts, was the first member of his troop to make Eagle Scout, and as guard on the Highland Park Scots football team played more minutes than any other player. At 133 pounds, he was the lightest member of his team; on defensive plays he would “submarine,” and he was given credit for more tackles than anyone else because he was always on the bottom in the pile-up.

When the Depression hit, the Jacobses closed their Second Avenue store, but they opened it again in 1936 to catch the trade from the crowds visiting the Centennial Exposition at Fair Park. They closed the Knox Street store to devote all their time to selling to tourists. It was a serious mistake, and the Jacobses went bankrupt. Ike graduated from Highland Park in 1937, and worked his way through A&M by waiting on tables. When he graduated in May 1941, he went into the army as a company commander of coast artillery.

Back from the war, he worked for a while as a junior superintendent for a construction firm until his older brother Joe, stationed in Germany with the air corps, decided against a military career and came back to help Ike get a start as a builder.

They began making the rounds of the major banks, all of whom refused to lend to would-be builders with no experience managing money. So they began seeking a backer among old Highland Park contacts; with about $10,000 in savings, they figured they’d need another $10,000 to start building some spec houses. Ike called on his old scoutmaster, George Bird. Bird sent him to talk to a friend, David G. Fox.

David G. Fox Sr. was 54. He had been transferred to Dallas by the American Baking Company in 1937 to be regional manager of the Taystee Bread division. He liked Dallas so much that when the company tried to send him back to Chicago after the war, he took early retirement rather than leave. The home building proposal attracted him – the postwar housing boom, fueled by Veterans Administration guarantees for mortgages, meant windfall profits for builders. He wanted an investment that wouldn’t jeopardize his savings, but he also wanted a potential job for his son, Dave Jr., who had started at A&M, spent the war flying B-29’s in the Pacific, and was finishing up at SMU. Fox agreed to back the Jacobses in their initial effort. He suggested that they build a house, sell it, and present the financial statement to Eugene McElvaney of First National Bank (McElvaney had been Fox’s banker when he was with Taystee Bread) as proof of what they could do.

Ike went to a pre-fab housing company and bought a small house, about 800-850 square feet, paying extra to change the elevation and some of the specifications. He had it hauled to a site north of the Carrollton business district and hired a crew to finish it. One of the plumbers who worked on the house bought it for $6500 – giving them a $1500 profit. They submitted the financial statement to McElvaney, who gave them an $80,000 line to credit.

The first Fox & Jacobs house still stands, at the corner of Donald and Random in Carrollton. It is bright yellow – Ike’s color choice. Always flamboyant, he had to argue down his conservative brother Joe, who wanted it white. The Jacobses built two or three more pre-fabs, then were persuaded by the carpenters who helped erect them that they could do a better job starting from scratch. The few houses they built in Carrollton are just a couple of miles west of where the Fox & Jacobs corporate offices now stand. There were no offices in those days; Ike and Joe operated out of a converted Taystee Bread truck.

Ike then heard about some lots that had been developed just north of Love Field, off Marsh Lane. He bought the land and began building two-bedroom, one-bath brick veneer houses. Joe Jacobs bought the first one for $11,300; the spare bedroom became the Fox & Jacobs office. The phone would ring late every Friday night as wives of construction crew members searched for husbands who had been paid but hadn’t made it home yet.

Mr. Fox maintained more than a financial interest in the project. He spent his weekends showing prospects through the little houses on Eaton and Hawick. Suddenly, at age 56, David Fox Sr. died of a massive heart attack. Dave Jr., who was on the road selling piece goods for a fabrics company, came back to take care of his father’s interest in the fledgling homebuilding company.

Mr. Fox’s management skills had kept Fox & Jacobs on an even keel for two years. Suddenly the firm was in the hands of two novices in the building market, venturing forth when that market was as unpredictable as the weather. They were a complementary pair: the handsome, affable Dave Fox and the aggressive, sometimes abrasive Ike Jacobs.

In the Housing Act of 1943, Congress had provided mortgage insurance for builders of apartment houses for war-industry workers. When the war ended, the program, Section 608 of the Housing Act, was extended to provide housing for veterans. The terms were almost too attractive to builders: The FHA guaranteed 90 percent of the “replacement cost” of the project and would underwrite anything it considered an “acceptable risk.” Builders raked in profits: FHA estimators sometimes approved loans in which the builder was borrowing as much as 30 percent more than the cost of the project. The FHA’s construction standards at the time were low, and its regulations enabled builders to cut corners. Lending amounts, for example, were estimated by room count rather than size.

Like all builders, Ike and Dave were attracted by Section 608. They found some land in northwest Fort Worth and built 342 units there between 1950 and 1952, more than two-thirds of them under Section 608. It was their first big financial success, but it was short-lived. Scandal hit the Section 608 program and Congress canceled it. At the same time, the Korean War created a demand for military base housing. Used to the lax specifications of Section 608, Ike and Dave submitted a low bid on the Red River Arsenal housing project and bought up the contract of some floundering builders who had made the low bid on the Quartermaster Depot in Fort Worth. Unfortunately, they failed to reckon with the Army’s propensity for red tape and found that specifications were so minutely regulated that costs easily got out of hand. They lost their shirts.

At the same time, nervous about the effects of the Korean War on the housing market, they decided to try making a killing in the commodities market, investing their profits from the Section 608 buildings. They were wiped out in a single day.

Just when they needed a break, one came. Bob McLemore, a land developer, offered Ike and Dave some lots off of Fisher Road, just north of Mockingbird Lane. McLemore had named the streets after race tracks: Pimlico, Santa Anita, Hialeah. In 1954, Fox & Jacobs built 40 houses there and sold them all without advertising. Dave Fox himself bought one; just married, he persuaded several of his friends who were also marrying to buy in the neighborhood. The houses had all the latest features: slab foundations, carports instead of garages, central heat – but not central air. Their style was the “California look” of the Fifties – low, slightly peaked roofs and high horizontal windows.

To sell their next development, east of White Rock Lake off of Buckner, Ike and Dave handed prospects a “check list” with loaded questions about the houses they were presumbly interested in buying. The prospect was supposed to check a “yes” or “no” answer to questions like “Is the house within three blocks of a school?” and “Does the house have a slab foundation?” Obviously the answer to all these questions was going to be “yes” when the prospect assessed the Fox & Jacobs houses. It was an obvious sales technique, but it was the first attempt to do more than just put up a sign saying “Houses for Sale.”

Dave and Ike were beginning to think about more than just building an occasional subdivision. Suppose the way to sell houses was the way General Motors sells cars: Find out who the buyers are and what they want, and then convince them that you’ve got the very thing they need at a price they can afford. Fox & Jacobs’ next subdivision, at Marsh and Walnut Hill, was named Timberbrook, and the streets had cozy names like Rockmoor and Woodleigh. But for the first time the houses had a brand name, too: The advertising agency Ike and Dave worked with dubbed them “New Horizon” homes.

“New Horizon” was more than just a new label on an old product, however. Fox & Jacobs became the first builder in Dallas, perhaps in the country, to build central air conditioning into all the houses in a subdivision. It was a logical step, given the climate and the technology. It also helped that Bob Frymire had been a classmate of Dave’s at A&M and wanted to establish his air conditioning business in Dallas. For the first time, too, Fox & Jacobs used a furnished model home, by working out a promotional deal with Anderson Furniture Company.

“New Horizon” sold well and attracted national attention, mainly because of the air conditioning. So in 1955, Ike, Dave, and Bob Frymire decided to check out the scene in Southern California, the breeding ground of the great American gimmick. They were particularly struck by the builders who sold houses by using fully furnished models – not just tables and chairs and beds and sofas, but ashtrays, stocked bookcases, table settings, flowers and plants, magazines on the coffee tables and toys in the children’s bedroom. They tracked down the designer of the most successful of these, Tony Pereira.

The last thing Pereira wanted to do was talk to three guys from Dallas he’d never heard of, but he finally agreed to meet them. They won him over with their enthusiasm, and he agreed to decorate the model houses in their next development. Pereira’s brother-in-law Don Edlund still decorates Fox & Jacobs display houses, shipping the furnishings, down to the crockery and silverware and books and toys, from California.

Back in Dallas, Ike and Dave got in touch with the town’s most successful ad man, Sam Bloom. Like Pereira, Bloom was initially skeptical about the visions of the two young builders who wanted to be the General Motors of the housing industry. But he agreed to help market their houses. They ditched “New Horizon” and cooked up “Flair for Living.” (According to one story, the name was suggested by the secretary taking notes at the brainstorming session.) The first Flairs were built in 1956 at Marsh Lane and Merrill Road, just north of the “New Horizon” development. Bloom hyped the development by having a high fence built around the model houses, then sending a newspaper photographer out to take a picture of a pretty girl on a ladder peering over the fence. At the grand opening, the fence was torn down and the public got its first glimpse of “Flair for Living by Fox & Jacobs.”

The development, featuring houses priced from $20,950 to $24,000, was a smash success.

General Motors became a model for Fox & Jacobs in more than marketing. Ike and Dave decided that manufacturing techniques, rather than construction techniques, were the key to success in mass home-building. They would try to set a building schedule with rigid deadlines for each house, and they would follow an assembly line procedure, adapted from the automobile industry.

Searching for a manufacturing superintendent, Dave and Ike ran a blind ad in the newspaper. The ad was answered by Jesse Harris, then superintendent of the Dallas production unit for Tide detergent. Harris was astonished when he found that the job he had applied for was with a company that built houses. He was more astonished when he found out that they wanted him to apply the manufacturing techniques of Procter and Gamble. Like Pereira and Bloom, Harris found his astonishment giving way to curiosity, then to enthusiasm.

One newcomer who jumped at the chance to join the firm was Jack Franzen, a salesman for Andersen Windowalls. Franzen had been in the building business all his life – even in the military when he worked with the Seabees. Franzen had moved to Dallas from his native Miami because he saw the potential for home-building here. So when Ike and Dave offered him a job as sales manager, he took it.

Franzen had immediate cause to regret his decision.

Julius Jacobs had given his son one piece of advice: “Don’t go across the river.” The city was growing north, he insisted, having failed in his own attempt to build a business in South Dallas.

But when Ike and Dave found some land off of Polk, south of Ledbetter, in Oak Cliff, they decided to go against Father Jacobs’s advice and open Flair South. The hype was intense. They opened the model homes on Easter Sunday, 1957, with red carpets and hostesses in dresses imprinted with the “Flair for Living” logo. Ten thousand people showed up for the opening.

When Jack Franzen started to work for Fox & Jacobs two months later, only one contract had been signed in Flair South. “I had a sick feeling,” Franzen says.

In those two months, the country had gone into a serious recession, Chance-Vought laid off workers, Collins Radio decided to move its corporate headquarters to Richardson, Oak Cliff voted dry, and interest rates jumped from 5 1/2 to 7 percent. And the tornado of ’57 made a direct hit on a Flair South model home.

Franzen had his work cut out for him. By the end of the year, Fox & Jacobs had sold about 50 houses – a fourth of their sales for the previous year.

Nevertheless, Ike and Dave moved ahead with plans to put Fox & Jacobs into year-round production. Up until then, like most builders, F&J would announce a new development in March or April, build the model homes, attract the customers, gear up for building their houses, then crank down again in the fall. In the three- to five-month period of dormancy, construction workers would seek jobs elsewhere. Fox & Jacobs would have to go through the slow and uncertain process of hiring and training entirely new crews each spring. With a year-round schedule, they could keep a steady supply of construction personnel, weeding out the unskilled and unreliable. They set a goal of one house a day, year ’round. And they met it swiftly: In 1959, Fox & Jacobs built 396 houses.

In 1958 they returned in triumph to North Dallas, with the Park Forest development at Marsh and Forest. By the time the development opened, on the first of April, 1958, 100 people held options on houses in Park Forest. F&J attracted customers by building a swimming pool open only to residents of the development. And they tried marketing a “component Flair” – a kind of do-it-yourself design in which the buyer could put together sections of the house – garage plans, bedroom plans, living-dining plans, for greater individuality of design. Unfortunately, the component Flair wasn’t cost-effective, and some of the salesmen, a bit baffled by the jigsaw puzzle approach, approved modifications that made the cost run away.

The top price of the Flairs in Park Forest was $35,000, and Fox & Jacobs began hearing requests for a lower-priced house. They worked up the design and created a new brand name: Accent. The first Accents, at Royal Lane and Channel, were rows of L-shaped houses with the ticky-tacky tract development look Fox & Jacobs self-consciously avoids today. But they were another best-seller: Half of the 500 houses built in the development sold before the model homes opened.

Unfortunately, the first Accents, which sold in the $14,500 to $18,000 range, were underpriced. Fox & Jacobs contracted to build at a fixed price, so any unforeseen increases in the cost of lumber or fixtures or appliances came out of the company’s pocket. The phenomenal demand for Accents, coupled with a sluggish cash flow and poor accounting practices, sent the company into a tailspin.

Dave Fox was beginning to worry about the bottom line, but Ike confidently expected a turnaround. Just keep building at greater and greater volume, he insisted, and we’ll put a lock on the market. So in 1960, F&J announced a classy development in the primest of locations: Royal Lane and Midway Road. The land was the most expensive F&J had ever bought. The development, called Les Jardins, was to be a custom home project in the then-premium price range of $35,000 to $50,000. But the designs Fox & Jacobs showed its prospects were only modifications of the component Flair plans it was building a few miles away in Park Forest and in the Glen Cove development at Midway and Forest. Les Jardins was a flop, eating up the profits F&J made in the early Sixties as it moved into the northern suburbs of Carrollton, Farmers’ Branch, and Richardson.

“Ike Jacobs was a dreamer.” Everyone says that, including Dave Fox, Joe Jacobs, Bob Bloom, Jack Franzen, and F&J’s design supervisor, Wayne Thompson. Thompson says that Jacobs seemed to believe that you could lose a little on every house you build but make up for it with volume. Building schemes of all sorts occurred to him. Once he asked Thompson to look into the possibility of building a high-rise condominium in downtown Dallas. As Jacobs envisioned it, individual units would be constructed on the ground, completely furnished, then hoisted into place by a crane. Something like that technique has since been used – Jacobs wanted to be the first. Another scheme, which went into operation for a while, was to grant franchises for Flairs and Accents to builders in five states. Not content with wanting to be the General Motors of homebuilding, Ike wanted to be the Howard Johnson’s.

“Ike dreamed of bigness,” Bob Bloom says. “Dave dreamed of success.” The dreams are compatible only if you can agree on how to achieve them. Dave and Ike couldn’t.

So in 1961 they agreed to disagree. Dave Fox asked out of the company. Ike agreed to a long-term pay-out.

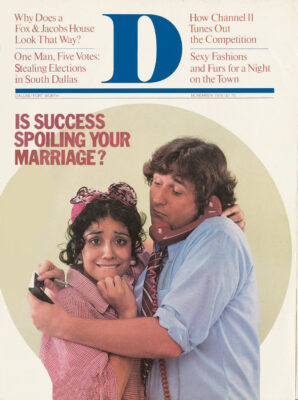

Ike Jacobs was a driven man, a workaholic whose marriage was foundering. The energy that got him started as an entrepreneur redoubled, however, and he devoted more and more of it to the business as he suffered personal setbacks.

The company didn’t thrive. From a peak year of 566 houses in 1960, sales declined to 479 in 1961, 490 in 1962, 331 in 1963, and 198 in 1964. Even in the midst of these problems, Ike was thinking big, proposing a development in Washington D. C., introducing new brand names, “Forecast” and “Dimension,” that have since disappeared. In the Glen Cove development northwest of Forest and Midway, F&J offered custom designs by big-name designers like William Snaith, of Loewy-Snaith, who created the first new Studebaker after World War II. Like the Studebaker, the house’s design, seen at 3920 Clear Cove, was strikingly ahead of its time. Also like the Studebaker, it was a flop.

In the spring of 1965, Ike came down with colitis. Work came first, and he dragged himself to the office. He refused, too, to postpone a scheduled vacation in Mexico, not the best place for a man with intestinal problems. He came back still sicker, but he continued to push himself. Finally, on a trip to Washington, his drive gave out. He entered a hospital in Dallas for several weeks, was released, then was rushed to Baylor Hospital with peritonitis. He lingered in intensive care for a month. Finally, his heart failed.

“He died of old age,” Bob Harper says, “at the age of 44.”

Joe Jacobs was left in charge of the firm. Joe had long since ceased to be active in the company, but with a 10 percent interest in the business and control of another 40 percent as executor of Ike’s estate, he had to figure out what to do next. Dave Fox, who had never received a cent of his pay-out, offered to buy Joe out, but Joe held out for a better offer. Finally, Texas Industries, Inc. offered Joe twice what Dave Fox was able to pay.

It was, Joe Jacobs says, a “shotgun wedding” for Dave Fox. He was left with half interest in a company whose other half was owned by a corporation listed on the New York Stock Exchange. He was a private individual having to act as if he were a publicly-owned company.

Texas Industries helped clean up the balance sheet and instill some of the accounting and management discipline the company needed. But while Fox had the security he lacked when he was teamed with Ike, the company wasn’t making the kind of money he wanted it to. Finally, Fox issued an ultimatum to TXI: Either buy him out, or he’d buy them out. TXI responded with an offer he couldn’t accept. So in 1969, Dave Fox took complete control of Fox & Jacobs.

He was broke again, having used up all his capital to buy up TXI’s interest, so he decided to get the company in shape and either go public or find a merger. Fox & Jacobs made an all-out growth spurt building in Grand Prairie and Cedar Hill and Lewisville and Piano and Garland, pushing its bargain-priced “Today” line, which rapidly became the company’s best seller. Advertising stressed the affor-dability of a Fox & Jacobs house and the advantages of buying instead of renting. Sales went up, up, up: 484 in 1968, 780 in 1969, 934 in 1970 – and then doubled in one year, 1905 houses in 1971.

Fox didn’t want to go public. In the great merger times of the early Seventies, he hoped to find his home in a conglomerate. He talked to scores of companies, but nothing acceptable presented itself. Finally, in the fall of 1971, Fox decided to go public and began to woo Wall Street. Having picked a brokerage house, he was on the verge of flying to New York to close the deal when Paul Seegers of Centex Corporation called. How about having a talk with him and Frank Crossen, Seegers said. Fox agreed to have breakfast with the president and chairman of Centex before he left for New York. He came away from the meeting with a merger.

The rest is a success story – steady growth for Fox & Jacobs with only one off-year, the industry-wide building slump of 1974. Even in the midst of that slump, when there was a 25-percent drop in building nationwide, F&J sales declined by only 9 percent and shot up again in 1975 to a mark 24 percent higher than the pre-slump level.

Even during that slump, F&J was digging into new markets, including the one that has been their greatest success – The Colony – and the one that has attracted the most publicity and elicited the greatest skepticism – the “in-town” East Dallas project.

The Colony, the Fox & Jacobs project that grew into a town, sprang up on the blackland prairie on the eastern side of Lake Lewisville in the summer of 1974. Even today, The Colony is miles north of the developments springing up along Preston Road. Hard to believe that 7000 people would choose to live out there, in the middle of nowhere. But they did, many of them employees of Mostek and TI and the other electronics companies that dominate the northern rim of the Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area. Fox & Jacobs provided sewage systems, streets, utilities, and emergency services for the community. It is something of an irony that The Colony grew and prospered while its neighbor, a highly-touted and federally-funded project called Rower Mound New Town, sank into debt and oblivion.

The success of The Colony had another unconventional spin-off. While boning up on solid-waste disposal at a UT-Arlington seminar, an F&J executive working on The Colony project was impressed by one of the speakers, Geoffrey Stanford, a British physician and environmental scientist. Dave Fox called him in for an interview. F&J had just acquired some land in Duncanville with an escarpment that wasn’t suitable for building sites but looked like it had some potential. What could they do with it? Stanford suggested an environmental research station. The idea appealed to Fox, who hired Stanford to create the Greenhills nature preserve, 800 acres where Stanford and his wife now conduct ecological research. F&J obviously hopes it will have practical spin-offs in helping them plan land use in future projects.

“We don’t follow the conventional wisdom,” Fox says. “We want to see what new ground can be broken, and look out a little farther in front than just next month or next year. Let’s see what impact we’re going to have on 1985 or 1995.”

Fox was chairman of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce for almost two years. His chairmanship coincided with his high visibility as the man who wants to build single-family housing almost downtown – a step that for 30 years or more no one has dared take. Fox & Jacobs began buying land near downtown in early 1974 – just as it was beginning its most distant suburb in The Colony.

“We had a gut feeling there was a market there,” Fox says. “Just like we had a feeling there was a market in Grand Prairie or Southwest Oak Cliff – nobody was building there when we went into those areas, either.” On the other hand, Grand Prairie and The Colony followed an established pattern of growth in concentric circles outward from the city. Fox says that some unusual factors also helped them decide to return to the inner city: The energy crisis and the success of the Swiss Avenue Historic District, he says, convinced them that people would want housing close to downtown.

At the same time, the Central Business District Association sponsored a survey by Alexander Cooper of New York which indicated that 24 percent of the workers in downtown Dallas were interested in some form of downtown housing. Even as the Cooper Report was being prepared, Fox was asking City Manager George Schra-der about possible city support for a downtown Fox & Jacobs housing project. Schrader was enthusiastic about the city’s largest builder making a move that would perhaps spark a revival in the downtown area, so he went to the city council with an Area Redevelopment Plan that would provide a “buy-back” guarantee from the city – a commitment to any qualified builder who would develop a housing project within a two-mile radius of downtown, that the city would pay him $2.25 a square foot if his project failed. In January 1977, Fox & Jacobs publicly announced its proposal to build 600 houses at a cost of $80 million in the area bounded by Good-Latimer, Ross, Haskell, and Floyd. So far, Fox & Jacobs is the only builder to obtain the buy-back guarantee from the city.

The coincidence of the Cooper Report and Schrader’s ARP proposal caught the imagination of at least the Dallas press, which has editorialized heavily in favor of the East Dallas project. There have been stumbling blocks: Dallas Legal Services flung up a challenge to the legality of the buy-back plan, claiming that it constitutes an urban renewal project and that all urban renewal projects in Texas have to be approved by public vote. Residents being displaced from the area sued the city for relocation funds. The challenges went nowhere in court.

Last January the city council agreed to increase the buy-back amount from $2.25 to $3.25 a square foot, reflecting what Fox said were increases in the cost of land in the area. Only Steve Bartlett, then a newcomer to the council, voted against the proposal; he objected that the plan was retroactive, affecting the land Fox had already obtained, and that the council was not being given enough time to study the effects such a retroactive agreement might have on future land costs in the project. As recently as March, Fox was encountering difficulties with absentee landowners in the area, who were happily sitting on their property waiting for F&J to pay what they were asking.

But last May, Fox announced he was ready to go with the first phase of the project, and in August he made preliminary reports to the plan commission and the city council announcing the “first phase” of the project: 15 acres and 140 houses, with an average selling price of $70,000.

“The response to the intown project is incredible,” Fox says, enthusiasm putting an edge on his otherwise underspoken manner. He admits that the project has risks, however. “It’s not easy. Hell, if it was easy it would’ve been done a long time ago. And we wouldn’t be there because that hole wouldn’t be in the market.”

That market is not the usual Fox & Jacobs market, however. Even though the Cooper report found that 24 percent of downtown workers wanted to live downtown, and that 65 percent of them would prefer detached houses over apartments or townhouses, there are those who think Fox has failed to figure in the Fox & Jacobs image as a suburban tract builder in his plans to go into the inner city. The East Dallas phenomenon, one veteran real estate developer says, is something entirely different. “That’s a case of people finding bargains, old houses with twice as much room as they can get in the suburbs, and the kind of individuality of design a mass-producer like Fox & Jacobs can’t give them,” he says. “Sure, they want to live near downtown, but do they want to live that near, and in something that new?”

Fox insists that they found the market the moment they made their first announcement in January 1977. Inquiries came flooding in, and the staff kept a record of the people who expressed an interest in the project. Then, last spring, when the time came to decide whether the project was “go” or not, they backtracked and did in-depth interviews with the people on the list. Those interviews formed the substance of Fox’s preliminary presentation to the plan commission and the council in August.

F&J discovered from the interviews that people were willing to pay more for intown housing than for suburban housing, figuring that the proximity to work was a trade-off. Since land costs in the inner city are 8 to 12 times what F&J encounters in the suburbs, there will be less land per home site. Parking and garage space will be tighter than in the suburbs. “A car is not king in their household,” Fox says of the people in his in-town market. “We’re gonna make it a little inconvenient to park in the development. When I made my presentation to the plan commission, somebody asked me, ’Isn’t everybody gonna have at least two cars?’ I said, I suspect everybody who is moving there already does have two cars, but a good many won’t keep both of them. After the meeting, a man came up to me and said, ’You were talking about us. I work down at the First National Bank building, and when we move down there I’m gonna get rid of one of my cars. I’ll either take a hop-a-bus, a bicycle, or a moped to work.’ So we’re not designing it as one of our suburban neighborhoods. These will be different people, different lifestyles, different values.”

The attempt to keep the development in character with East Dallas means other design changes, including big front porches, peaked roofs, and some two-story houses. These design changes consequently mean changes in the construction processes F&J has honed to assembly-line efficiency through years of suburban building. Using the auto industry analogy that comes so readily to the Fox & Jacobs staff, Wayne Thompson says building houses in the intown project will be “like putting a Cadillac on a Volkswagen assembly line.”

The next step for Fox & Jacobs is approval of specific proposals for street alignments, easements, and utilities. Fox’s proposal to close Hall Street through the development has already encountered opposition from council members John Leedom and Lucy Patterson. Assuming that Fox can cut through red tape, he plans to be “pushing dirt around” by January, to have model houses open by spring, and families moving in by summer.

Will the project work? “It’s still a risk,” Fox says. “We may not be able to buy enough to get a significant critical mass. We don’t even know what that is. We know it’s more than five and less than a hundred acres. But we still don’t have it.” The main thing, however, is proving that it can be done. “I’m concerned,” Fox says, “that if we don’t succeed, people will say ’there isn’t a market there and we told them so’ – and that would set the whole philosophy of revitalization back. But it’s not true, there is a market there.”

If there is, nobody’s in a better position to know it than Dave Fox.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte