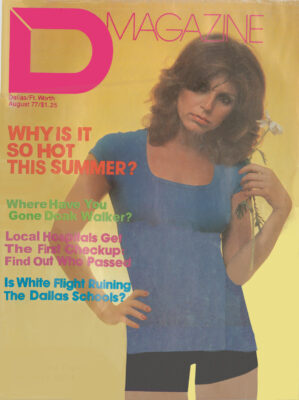

Driving south out Colorado Boulevard in Denver to see Doak Walker, one feels uneasy. Off to the west are the Rockies, a reminder that some things stand unchanged for millions of years. But not many. The sinking feeling sets in that talking with Doak 30 years after his legend blossomed and 20 years after he left it behind in Dallas will unavoidably diminish the legacy.

Driving south out Colorado Boulevard in Denver to see Doak Walker, one feels uneasy. Off to the west are the Rockies, a reminder that some things stand unchanged for millions of years. But not many. The sinking feeling sets in that talking with Doak 30 years after his legend blossomed and 20 years after he left it behind in Dallas will unavoidably diminish the legacy.

Doak. Perhaps no first name ever needed a last name so little. Now here was an honest-to-God hero – a cut of American youth more All-American than Jack Armstrong himself. Peewee football players argued over who would wear Doak’s number, 37. Boys named their dogs after Doak. Fathers named their sons for him, hoping that their sons too would be Ail-American. Not necessarily Ail-American on the football field, although that would be a bonus for any father. Ail-American in heart and soul, like Doak, a humble Highland Park youth who drank nothing stronger than milk, asked his sweetheart to wear his golden football emblem and every Sunday faithfully attended Sunday school class.

Thirty years later most of those sons are now fathers and their fathers are grandfathers, yet they remember the time when they saw Doak. Perhaps he was on the field engineering a breathtaking, last-second drive against TCU. Maybe he was limping on the sidelines during the Notre Dame game or strolling across the campus with beautiful Norma. But they do remember. They remember the strange romance of a young man and an era which spun a legend neither dimmed by time nor eclipsed by something even more Ail-American.

Walker’s spacious Cherry Hills condominium attests to his success. The development is surrounded by a brick fence and its entrance is guarded by security personnel, who take note of strangers entering the development. Walker’s condo is a short distance inside the gates.

The door stands open, unattended, implying a sense of cordiality. At the ring of the doorbell, Walker strides around the corner into sight, heavier than in his college publicity photos, but still a bull of a man in his deeply tanned arms and neck. His hair is thinner and slicked down, tamed a bit since his college days. One thing remains absolutely unchanged – his deep-set azure blue eyes, casting an almost hypnotic stare.

There is an irresistible temptation to expect Doak’s words and thoughts to flow with the same magic he used to glide through an opponent’s defense. Surely a mind that could plot a swift and certain path 25 yards ahead on the football field could talk about it in flowing terms 30 years later. Of course he’d like to relive those glorious days when he had enemies’ defenses and the city of Dallas falling at his feet.

As a young man Walker wasn’t much of a talker, but so what? People wrote about what he did, not what he said.

At 50, Walker is scarcely a big talker. (Aren’t heroes automatically great talkers?) Questions about his football feats usually elicit short, unadorned answers accompanied by an apologetic chuckle. The interviewer supplies the poetry and Walker approves or disapproves of one’s analysis of his life.

The listener’s irresistible desire is to hear Walker live the legend again, to say how much he still loves Dallas, God, mother and apple pie, in that order. After all, how could he leave Dallas, which tell at his feet? How could he have moved to Denver 20 years ago abdicating his throne as Dallas’ greatest hero? That sort of talk finally draws out the man.

“After college I accepted invitations night after night to school banquets, church dinners and everything else,” he says. “I was out practically every evening, thinking that this was one way I could repay what football had done for me. Looking back, I can see that was really stupid,” Walker explains. “I didn’t make the money I should have. I shouldn’t have done it all for free. It took me a long time to realize that nobody’s going to take care of Doak Walker but Doak Walker. It was easier for me to leave Dallas than to say ’no.’”

Walker moved to Denver 20 years ago in a routine job transfer with the George A. Fuller Company, a general contractor. He has lived there ever since and has no intentions of leaving. “I want to live the rest of my life right here,” he says. The conversation turns to Walker’s remarkable fate, or predestination, as he prefers to call it, which led him to take the leading role in what now seems almost a fantasy.

Ewell Doak Walker was born January 1, 1927, into what would become the A1I-American family. His father spent a career coaching, and later in administration, in the Dallas Independent School District. Doak’s parents raised their children properly, teaching them respect and instilling in them a good measure of humility.

As a boy Doak’s hero was Harry Shuford, number 37, star running back on SMU’s 1935 national championship team. (Shuford, 62, is now board chairman of First National Bank.) Occasionally Doak’s father would take him over to watch SMU practice football. After hustling through drills, Shuford often came over to talk with Doak, a gesture Doak never forgot even after he eclipsed Shuford’s fame.

In high school Walker teamed with Bobby Layne to make Highland Park one of the better known football powers in Texas, reaching the state quarter-finals one year, the semi-finals the next and after Layne was graduated, the state finals. Layne went on to attend Texas, leaving Walker behind for one last season at Highland Park.

After graduation Walker joined the Maritime Service, receiving an early discharge halfway through the 1945 football season. Playing only the second half of SMU’s 1945 schedule, Walker made All-Conference and the legend sprouted, postponed by one year in the army, 1946.

When he returned for the 1947 season, Walker arrived with incomparable foot-! ball talents at the perfect moment in history, to become the most famous college football player ever to run onto the field.

Here was a nice, clean-cut boy from a fine family, exceedingly humble, a boy who could do it all on the gridiron. He could run, throw, catch, punt, place kick and play tenacious defense. While a fresh-man he met a beautiful girl who had be-come his girl and they were frequently photographed together. Doak was the American dream. He was strong, handsome, humble, loyal and true.

There was little to distract people from his heroics – pro football wasn’t too important. The nearest teams were in Chicago. There was no television or air-conditioning to speak of; in short, nothing to keep people at home. Dallas was a city of no national importance, population 400,000, with a skyline topped by Mercantile National Bank and the Mobil Building’s flying red horse. The housing boom was rac-’ ing north across Northwest Highway, approaching Walnut Hill Lane.

Doak’s legend burgeoned in a time whose robustness is perhaps best illustrated by women’s fashion. Gone was the mannish wartime look. It was replaced by a titillating new look in women’s clothing – cinched waists, rounded hips and uplifted, pointy bustlines. There was excitement and romance – Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip were married, Howard Hughes flew his 200-ton Spruce Goose, and the Yankees beat the Dodgers in the seventh game of the World Series. Out of this tableau came the Ail-American boy.

It began 30 years ago this fall, Saturday, September 27, 1947, in Kezar Stadium, San Francisco. With only 7,500 spectators present, the 60,000-seat arena seemed almost empty. SMU whipped Santa Clara 22-6, with Walker scoring all but two of the Mustangs’ points. His first touchdown came on a 44-yard dash over left tackle. The second on a six-yard dive over left guard. The third on a stunning 96-yard kickoff return, at the time the longest runback in SMU history. Walker kicked two extra points and intercepted two Santa Clara passes.

Going into the 1947 season Rice had been a heavy favorite to win the Southwest Conference. Rice – which lost to LSU that day – and Texas received the biggest headlines during the first few weeks of the season. But the weeks rolled on and Walker continued to perform his magic. The nation began to take note.

Dallas, October 4 – SMU downs Missouri 35-19 before 26,000 in the Cotton Bowl. Walker scores two touch- ; downs and kicks three extra points.

Stillwater, Okla. October 11 – Walker scores one touchdown, passes for another and kicks three extra points as SMU defeats Oklahoma State, 21-14.

Dallas, October 18 – SMU shuts out preseason favorite Rice, 14-0, before 22,503 at Ownby Stadium. Walker scores one touchdown and kicks both extra points. He completes four of five passes and intercepts two Rice aerials.

After the Rice victory it was obvious, that SMU and Doak Walker were something extraordinary. SMU faced its biggest tests yet during the next two weeks. First an airplane flight to California, to take on UCLA.

Los Angeles, October 25 – Walker scores all seven SMU points in its 7-0 win over UCLA. Passing from quarterback Gil Johnson and the running of fullback Dick McKissack aid in the victory before 64,197 fans, including the SMU band, men’s chorus and 700 Mustang fans who made the trip.

Dallas, November 1 – Fifty thousand fans overflow the Cotton Bowl as SMU and Texas, both undefeated, square off for the conference lead. With Doak Walker at the helm for the Mustangs, SMU defeats Texas 14-13 for the first time in eight years. Walker is bottled up, being held to two-for-two passing, two extra points and one interception, Bobby Layne and Tom Landry star for Texas.

After having won the first five games, SMU continued to roll over conference opponents, who began to double-team Walker.

College Station, November 8 – After suffering eight straight losses to A&M, SMU whips the Aggies 13-0 before 28,000 in Kyle Field. Star of the day is SMU passer Gil Johnson, who connects on 14 of 16 attempts. Walker is two-for-two passing and kicks one extra point.

Dallas, November 15 – Falling behind for the first time in 1947, SMU recovers from a 6-0 deficit and comes back to down Arkansas, 14-6. Playing with a sore ankle Walker scores one touchdown, kicks both extra points, returns a kickoff 46 yards, completes one pass and catches four more. Fullback Dick McKissack carries 22 times for 90 yards.

Waco, November 22 – SMU shuts out Baylor, 10-0, before a sparse rainy day crowd of 12,000. Walker kicks one field goal and an extra point. He carries the ball 17 times for 93 yards as the Mustangs clinch their first trip to the Cotton Bowl.

Having only to down TCU to finish the regular season untied and unbeaten, SMU traveled to Fort Worth for its November 29 confrontation, which would be the first of three season ending games against TCU that no witness, least of all Walker, can ever forget.

Walker’s performance in the 1947 TCU game was staggering. He finished with 119 yards rushing, 10 of 14 passes, three kickoff returns for 163 yards (still a school record) two touchdowns and an extra point. TCU led in the game, 19-13 with only 90 seconds remaining. Walker took a TCU kickoff at the SMU eight-yard line, danced up field spinning through one TCU defender after another to the TCU 35, where he was tackled. Passing ace Gil Johnson came in and hit Walker with a 40-yard bomb to the TCU nine. As an electrified crowd of 30,000 watched, Johnson hit Sid Halliday, on his knees in the TCU end zone, for the tying score with 25 seconds left. SMU had driven 92 yards in one minute and five seconds, needing only the conversion to win the game 20-19 and finish the regular season with a perfect 9-0 record. Walker came in for the kick but missed, in the greatest disappointment of his college career.

On January 1, 1948, SMU faced untied, unbeaten Penn State in the Cotton Bowl, a team which had given up only 27 points all season. Led by Walker’s touchdown and extra point, SMU jumped out to a 13-0 lead but Penn State came roaring back to tie the game at 13-13. On the last play of the game a Penn State receiver dropped the winning touchdown pass in SMU’s end zone. He rolled over in disgust, then leaped up and shook Walker’s hand.

At season’s end, Walker was named All-America, a rare honor for a sophomore. Perhaps no other single statistic better exemplifies the excitement of Walker with a football than his 1947 kickoff return average – 38.7 yards, a Southwest Conference record which stands today.

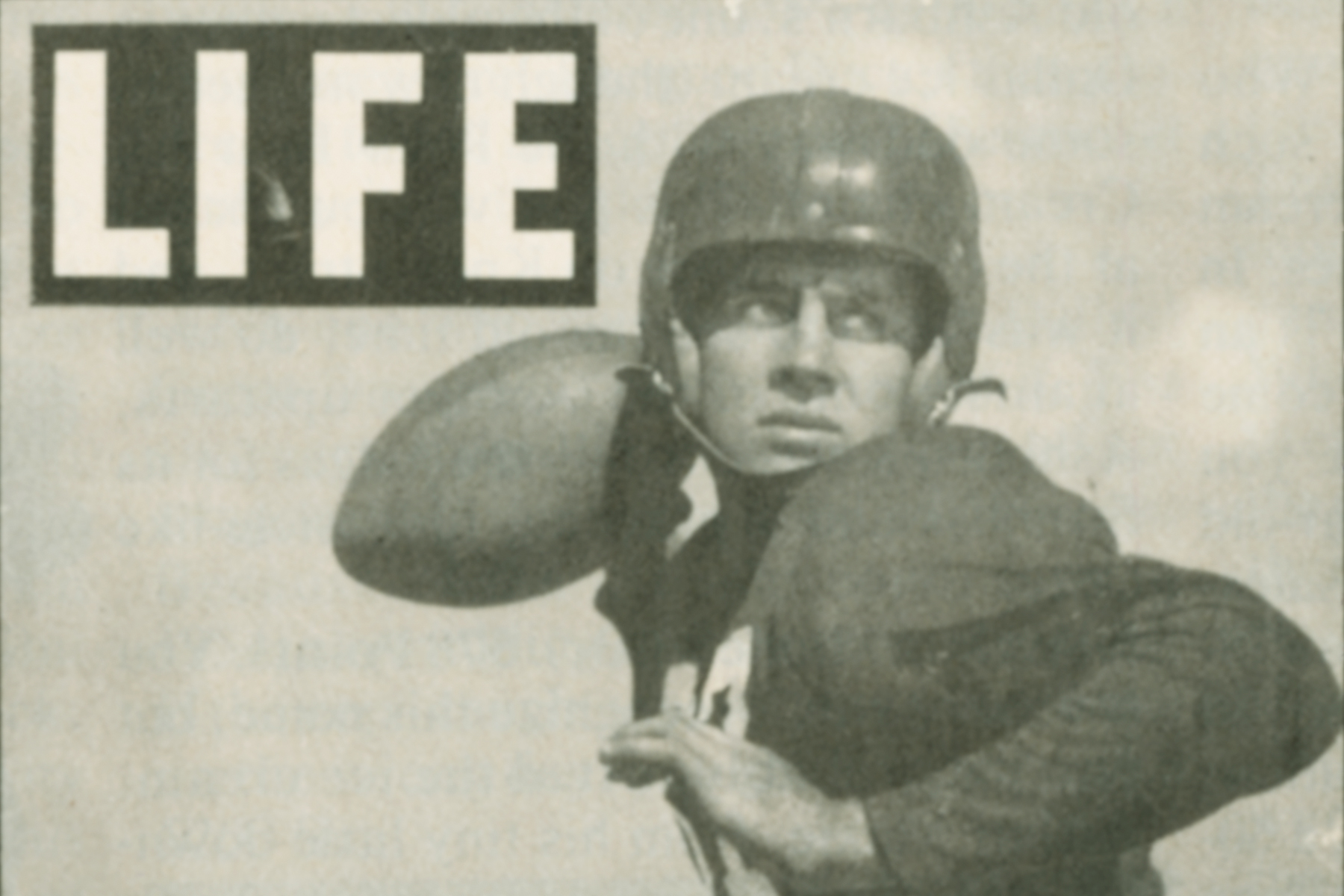

By 1948 Walker and his backfield were appearing on one magazine cover after another. Eventually the total would reach 50, including Life, Look and Collier’s, the leading magazines of their day. The Look spread was a classic – two pages of Walker playing football and another two pages of Walker and sweetheart Norma wearing western outfits.

Although SMU’s 1947-48 teams probably weren’t as good as the national championship team of 1935, which had three Ail-Americans, something about Walker and SMU fascinated American writers and editors. Seldom did a day go by without a Walker story request submitted to SMU’s publicist Lester Jordan. Walker was receiving 50-100 fan letters a day, to which he personally responded with post card photographs of himself supplied by Jim Laughead.

“Doak was a wonderful boy,” Jordan recalls. “He never missed an appointment with a single writer or photographer. He was so patient he’d do anything for them. One time a photographer was having trouble shooting a picture from a particular angle of Doak kicking a field goal, so he asked Doak to kick left footed. Doak did, and the photographer got his picture.”

As if the 1948 team didn’t have enough going for it with returning 1947 stars, a-long came Kyle Rote, who had led the freshman team to a 5-0 season. Rote was a fabulous runner out of San Antonio, gifted with the speed of a halfback, the power of a fullback and the hands of a great receiver.

With the addition of Rote to SMU’s ’48 backfield, SMU’s prospects seemed awesome, but many sportswriters were picking Texas to win the conference. Others picked Rice. No team had ever won the Southwest Conference two years in a row except in wartime, which really didn’t count. Perhaps that jinx spooked the writers, or maybe SMU’s size, which was an integral part of its image.

Everybody likes to root for the little guy and cheering for SMU was in fact rooting for the little guys. SMU’s players were dwarfed by most of the conference, especially the bruisers of Rice and Texas. What SMU didn’t have in size it made up for with razzle-dazzle provided by assistant coach Rusty Russell, who designed the Mustang offense. The Russell offense was exiting, filled with pitch outs, shovel passes, screens and flea flickers. The fans loved it. The SMU defense, designed by head coach Matty Bell, starred many of the team’s best offensive players, including Walker.

SMU opened the ’48 season in Pittsburgh by thrashing the Pitt Panthers 33-14. Passing ace Gil Johnson hit nine pas-ses in nine attempts, a feat which stands unmatched in the SMU record books. Walker was his usual self, catching one touchdown pass, returning a punt 75 yards for another touchdown and kicking three extra points. He also connected on four out of five passes. The fifth was dropped.

Next the Mustangs destroyed Texas Tech, 41 -6. Walker played part time, scoring one touchdown, passing for another, kicking three extra points and returning a kickoff 47 yards before slipping and falling down. It was SMU’s last football game in Ownby Stadium. The prospect of another fabulous season had led Cotton Bowl officials to renovate the stadium completely and add an upper deck, boosting the bowl’s capacity to 67,500. It became known as the house that Doak built.

Three of the next four games promised to be tough contests. SMU’s chance at a perfect season went down the drain October 9, in Columbia, Missouri. The largest crowd ever to watch a Missouri home game jammed into Memorial Stadium to delight at Missouri’s upset of SMU, 20-14. Walker carried one touchdown, caught a pass and ran 58 yards for another TD, kicked both extra points, hit three of six passes and intercepted two Missouri aerials. Playing with an injury, Gil Johnson completed 13 out of 19 passes.

As if SMU was offended by the loss to Missouri, the Mustangs roared back and vanquished one foe after another.

Playing before a sellout crowd in Houston, SMU destroyed Rice 33-7. The next week 50,000 Cotton Bowl fans watched the Mustangs demolish Santa Clara 33-0, followed by a 21-6 win over Texas in Austin before the largest crowd in conference game history, 68,750. SMU then returned to the Cotton Bowl to whip A&M 20-14, with 53,000 fans looking on. Arkansas fell before a sellout crowd in Fayetteville, 14-12 and SMU edged Baylor 13-6 in Dallas before 58,000. In this six-game winning streak Walker personally scored 49 points and threw four touchdown passes, while the running of Dick McKissack and Kyle Rote, along with Gil Johnson’s passing, was superb.

SMU prepared to face nemesis TCU on November 27. Going into the game with an 8-1 record, SMU was a heavy favorite but again TCU stunned the Mustangs. TCU led 7-0 with one minute 41 seconds remaining in the game, before a spellbound Cotton Bowl crowd of more than 67,000. SMU began its final drive on its own one-yard line. Five plays later SMU scored with 15 seconds to spare. Walker added the extra point, giving SMU a 7-7 tie.

In the January I, 1949, Cotton Bowl, Walker and Rote led SMU to a 21-13 victory over Oregon and quarterback Norm van Brocklin. Walker scored one touchdown, kicked two extra points and was six for ten in passing. Rote carried 16 times for 104 yards and caught four passes for 55 yards. Both Rote and Walker quick-kicked, furnishing the most memorable moments of the game. Rote’s kick was launched near the SMU goal line and traveled 84 yards to the Oregon 12. Walker booted his from SMU’s 20 yard line. The ball came down on the Oregon 35 and rolled to within six inches of the Oregon goal line, where it died.

After the 1948 season Walker was named All-America for the second time and won the Heisman Trophy, the first junior ever to win college football’s most prestigious award. He set a Southwest Conference season scoring mark of 88 points, a record which has been challenged only by his own 87 points in 1947 and 83 points in 1949.

The Walker era had an innocence about it. Until about 1950, most schools played one platoon football, that is, the best players stayed in for both offense and defense. One-platoon football gave a young man like Walker an opportunity to prove his versatility, creating the image of the complete star. Today college football mimics the pro system of gridiron “specialists,” a system which develops a player into a specialist in one position on offense or defense. That’s why there will never be another Doak Walker. If he played today Walker wouldn’t be allowed to go out and do it all for 60 minutes. Some of the ’47-48 football players actually played basketball for SMU, an unheard of practice today. Walker played one year and end Bobby Folsom played varsity basketball for several seasons.

In this innocent era, heroes were portrayed as heroes. If a sports hero had any bad habits writers didn’t point them out. Doak drank milk, had a steady girlfriend and went to church on Sunday, but even if he had carried on like Joe Namath it probably wouldn’t have made the sports pages.

Sports in the fall of 1949 was dynamic. The Yankees and Dodgers won their respective pennants on the final day of the season. Football powerhouses were Notre Dame and Army, both with enormous followings.

SMU played eight home dates in the ’49 season and the crowds were enormous – averaging 60,000. By fall a second upper deck had been added to the Cotton Bowl, increasing seating capacity to 75,504. Fifty-one thousand saw SMU beat Wake Forest in its opener and 58,000 watched SMU avenge its 1948 loss to Missouri. Walker was incredible, scoring three touchdowns, kicking four extra points and gaining 105 yards on 29 carries. The crowds grew larger yet, with 71,000 nearly filling the Cotton Bowl for the Rice game. Rice, led by Kyle Rote’s cousin Tobin Rote, gave SMU its worst conference beating in history, 41-27. The defeat was resounding. When time expired Rice was sitting on SMU’s one yard line.

The next week SMU bounced back to beat Bear Bryant’s Kentucky Wildcats, an undefeated team which had outscored its five opponents 206 to 7. Walker was out with the flu but Rote and Dick Mc-Kissack carried the day, 20 -7. On October 29 the second largest crowd to ever see SMU play at home (topped only by the 1950 A & M game) saw SMU down Texas 7-6 in a thriller. With nine seconds remaining Texas end Ben Procter dropped a 50-yard pass which would have given the Longhorns the game.

After the Texas victory SMU’s fortunes turned sour. Injuries riddled the line-up and although Walker scored eight touchdowns in the next three games, SMU managed only one win, a tie, and an ignominious 35-26 loss to Baylor, the first time Baylor had beaten SMU since 1936. During the Baylor game Walker suffered a charley horse which wasn’t discovered until he cooled off after the game. Walker tried to play with the muscle spasm the following week against arch rival TCU, but made the injury worse. This time there were no last second heroics to rescue SMU from defeat. TCU won 21-13, and although Walker didn’t know it, his foolish attempt to play on an injured leg would keep him out of the last game of his college career. It would be the greatest game in SMU history. Walker watched it from the sidelines.

The only thing which could have topped the arrival of the Notre Dame football squad in Dallas on Friday, December 3, would have been the Second Coming. Notre Dame was the greatest college football machine in American history. Since the turn of the century Notre Dame had suffered only one losing season and had spun out legendary figures such as Knute Rockne and George (“Win-one-for-the-Gipper”)Gipp. The 1949 Irish squad was no exception. Coming into the SMU game Notre Dame was 9-0, having easily destroyed all of its opponents. Over the last four seasons the Irish record stood at 35 wins, no losses and two ties. Notre Dame hadn’t played in Texas in 34 years and Dallasites were awed when a special 14-car Sante Fe train pulled into Union Sta-tion carrying the Irish warriors. The Notre Dame squad went directly to a special mass in Sacred Heart Cathedral on Ross Avenue, which drew 1,200 persons.

The only thing which could have topped the arrival of the Notre Dame football squad in Dallas on Friday, December 3, would have been the Second Coming. Notre Dame was the greatest college football machine in American history. Since the turn of the century Notre Dame had suffered only one losing season and had spun out legendary figures such as Knute Rockne and George (“Win-one-for-the-Gipper”)Gipp. The 1949 Irish squad was no exception. Coming into the SMU game Notre Dame was 9-0, having easily destroyed all of its opponents. Over the last four seasons the Irish record stood at 35 wins, no losses and two ties. Notre Dame hadn’t played in Texas in 34 years and Dallasites were awed when a special 14-car Sante Fe train pulled into Union Sta-tion carrying the Irish warriors. The Notre Dame squad went directly to a special mass in Sacred Heart Cathedral on Ross Avenue, which drew 1,200 persons.

The game was a classic confrontation. Methodist vs. Catholic. South vs. North. David vs. Goliath. David appeared in the person of Johnny Champion, a reserve SMU back forced into action by injuries to first stringers. Champion, whose name couldn’t have been more apt, stood 5’4″ and weighed about 160 pounds. As a wing back, Champion’s assignment would be to help Dick McKissack block Notre Dame’s awe-inspiring Goliath, Leon Hart, a three time All-American defensive end who stood 6’5″ and weighed 280 pounds. In 1949 Hart would win the Heisman trophy, a rare honor for a lineman.

More than 80,000 fans jammed into the Cotton Bowl to see if SMU, without Walker, could make a respectable showing.

Injury-ridden SMU was a 28-point underdog. The game attracted national attention because it was the last week of the season and Notre Dame was bound for a perfect record along with the national title.

While Doak Walker watched, dressed in street clothes and standing on the sidelines, Notre Dame started as expected. The Irish scored the first touchdown but SMU gamely fought back in the second quarter, driving to the Irish six-inch line before surrendering the ball on downs. Then Notre Dame began driving back relentlessly. At the SMU 35-yard line the Irish threw a 28-yard pass to halfback Ernest Zaleski. The pass was underthrown and three SMU defenders went up to intercept it. Instead they tipped the ball forward to Zaleski who caught it at the eight and ran in for Notre Dame’s second touchdown. That tip proved to be the difference in the game.

By the end of the third quarter Notre Dame led 20-7 and SMU’s case seemed hopeless, as expected. But then the Mustangs, led by Kyle Rote, began driving. They scored two touchdowns in the final period, tying the game at 20-20. An exuberant SMU fan ran down on the field and shouted in Notre Dame coach Frank Leahy’s face “What do you think of it now?” Leahy told him to “Get out of here.”

But the inevitable happened – Notre Dame took the ball and ploughed through the undersized, undermanned Mustangs, scoring a final touchdown and winning the game 27-20. If it hadn’t been for the tipped pass, SMU probably would have tied Notre Dame and the game would have been one of the greatest upsets in history.

As it was, the game was recorded at the top of sports pages across America as the greatest game of the season. The day was best symbolized by Johnny Champion, who cut down giant Leon Hart all afternoon while Kyle Rote attempted to work miracles at tailback.

Perhaps no single performance in SMU history will ever match that of Kyle Rote’s. He ran for 115 yards and completed l0 of 24 passes for 146 yards. Time after time Rote fought off Notre Dame’s huge defenders in a gallant effort to escape the inevitable. Rote was voted unanimous All-Conference and the Washington D.C. Touchdown Club cited him for the season’s most outstanding single-game performance. Walker was named All-America for the third year, an extraordinary honor. But perhaps the highest honor of the day was reserved for little Johnny Champion, who left a picture indelibly imprinted in the minds of 80,000 spectators – the sight of Champion hurtling his 5’4″ body at the legs of giant Leon Hart, and Hart tumbling to the ground.

So ended the glory era of SMU football. Although Kyle Rote played one more year and led SMU to an early season 5-0 record, the Mustangs lost four of the season’s last five games. Rote made All-America that year, but SMU was never again the same.

Today coach Matty Bell, 78, lives in University Park and still speaks in the stentorian tones which marked his days on the practice field. Because of cataracts Bell rarely attends football games, but watches them avidly on television. “I got more credit for losing to Notre Dame than I ever got for winning,” he chuckles.

Coach Rusty Russell lives in a Richardson apartment, and, at 81, still tells stories well. Russell’s face is as red as a Mustang jersey and his head is topped with a shock of wavy white hair. He too has difficulty seeing games in person. Russell attended a Highland Park game last fall with Doak Walker’s father. They went to see Doak’s son, Rusty (named for Russell) who plays for the Scots. Russell’s football philosophy, which generated delight for hundreds of thousands of spectators, hasn’t changed. “Anybody can go out there and butt heads,” Russell smiles. “But it takes some brains to spread out and play football from sideline to sideline and goal line to goal line.”

Dick McKissack, 51, still lives in Dallas and is vice president of a chemical company. He is in excellent physical condition, rising five mornings a week just after five a.m. and jogging two miles.

Kyle Rote, 48, weighs about as much as he did during his playing days, but jokingly says “My weight has shifted a little.” Rote spent 11 seasons with the New York Giants and was an excellent receiver, although his real potential was never realized. In a pre-season practice session before his first game with the Giants Rote stepped in a hole and injured his knee. Never again did Rote run as he did at SMU. Unlike Walker, Rote made the transition from sports hero to media celebrity, spending 13 years doing radio and television sportscasts in New York as well as pro football commentary and most recently, a Mr. PiBB commercial with Kyle Jr.

Rote lives in a comfortable East Side Manhattan apartment, and like Walker, is very gracious. He still has a rugged look about him, wavy hair with gray creeping up the sides, large, powerful hands and narrow eyes. He strides down Fifth Avenue at a pace which would test any running back, heading to a private club to talk about his career.

Rote is in the air freight forwarding and chemical businesses and loves life in New York. He rarely attends football games but still watches them avidly on television. Rote’s idea of recreation is tennis and golf. In quieter moments he writes poetry and lyrics. “Right now my leading interests are the kids and business, but one of these days I’d like to retire to the beach and write poetry,” he says, puffing on a Marlboro.

Gil Johnson, 53, leads a quiet life in his home near White Rock Lake, after suffering two heart attacks. Johnson, a delightful story teller, owns a service station and auto repair center in East Dallas. Johnny Champion, SMU’s sentimental hero, died several years ago.

Several other members of the’49 team have gone on to very successful careers, each in a different way. Center Dick Davis resigned his position three years ago as vice president of Merrill Lynch to become SMU’s athletic director. End Bobby Folsom made millions in real estate and is now mayor of Dallas. Guard Jack Atkinson is Dallas’ pro wrestling promoter and has made an excellent living by wrestling under the name Fritz von Erich.

Doak Walker’s life after graduation was bittersweet. Many people doubted that he was big enough (5’10″, 165 pounds) to play professional football, but he proved the doubters wrong. Walker signed a $27,000-a-year contract with Detroit in 1950, an extraordinary amount considering that the average Detroit salary was $6,000. Walker made All-Pro his first year and led the National Football League in scoring on a team that finished fourth in its division. He played six seasons, making All-Pro four years and again winning the league scoring title in 1955, when Detroit was the worst team in the NFL.

“I decided to quit,” he says, “when the bruises weren’t healing as fast as they used to and the holes were closing a little quicker. What more could I do anyway? I made All-Pro four times and Detroit won the NFL title two years.” Walker retired after the 1955 season but returned for Detroit summer training camp in 1957. After a few days he changed his mind, leaving camp at two in the morning, flying back to Denver.

Walker’s only other involvement with football came during a year as an assistant coach with the Denver Broncos, ending when he was swept out in a management change. During the Sixties Walker contacted Detroit head coach Joe Schmidt and Cowboy coach Tom Landry, hoping to catch on as an assistant, but “nothing much ever came of those phone calls,” he says. A decade after Walker stepped off the playing field, he was through with football for good.

During the pro football off seasons Walker lived in Dallas, attending banquets and working for the George A. Fuller Company. He also invested a substantial sum of money in Doak Walker Sport Centers. Although Walker has no day-to-day connection with the stores, he remains a director and owns 30 percent of the business.

In 1966 his marriage to SMU’s 1948 homecoming queen, Norma Peterson, ended in divorce, and he has since remarried. Walker’s wife is Skeeter Werner, a 1952 U.S. Olympic skier. They own a home in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, where Walker spends many of his weekends, returning to Denver in the early morning hours on Monday. He occasionally attends a Denver Broncos’ game, but really is more interested in fishing, hunting, skiing and playing golf (he shoots in the high 70s and low 80s). “I lead a great life here.” Walker says. “I have a great wife, a great place to live and work for a fine company, Fischback & Moore, an electrical contractor. I never want to leave Colorado.”

Perhaps the most sensitive point in the conversation arises when Walker again fields questions about why he left Dallas and has no intention of returning. When asked if there were any disappointments which caused him to consider leaving, Walker firmly replies “I just don’t want to comment on that. It’s none of anybody’s business.” Several more efforts to get Walker to comment on the subject are futile. He simply smiles and says “Nice try. but I’m not going to talk about it.”

When asked if he ever comes back to Dallas or pals around with his old SMU teammates Walker says that he does occasionally but repeatedly makes the point that he takes care of “business” first and then if he has time he visits with old SMU friends.

Walker returns to Dallas on business every couple of months and tries to arrive in town a night early so he can visit with his father and his children, two of whom still live in Dallas with his former wife. Walker’s public appearances in Dallas are rare.

Next fall SMU will host the most distinguished out-of-state football team – O-hio State – to play SMU since Southern California in 1962 or Notre Dame in 1958. Plans have been building for months in an attempt to sell out the Cotton Bowl, in hopes of boosting SMU football and proving that SMU can send a distinguished visiting team home with a sizable paycheck.

The October 1st Ohio State game will be played 30 autumns after Doak Walker stepped onto the Cotton Bowl grass with the first of three glorious SMU teams.

To the younger folks sitting in the Cotton Bowl’s 72,000 seats, the game will be something new – the excitement of a big crowd and an awesome foe. For older spectators there will be yet another feeling, the memory of having seen something like this before. They will remember when the red helmets and silver pants scrambled all over the Cotton Bowl’s grass, long before television, air-conditioning and the Dallas Cowboys. They will remember another Saturday’s red-shirted heroes. It is an era that belongs to itself. Never mind that we and our heroes grew up, realizing that our assessments of each other were nurtured in a time we can’t recover, an innocence lost forever.