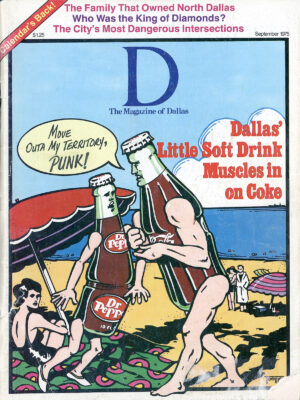

One crisp November morning in 1969 Woodrow Wilson “Foots” Clements and his team of executives stepped into a cab outside New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Mission: To pull off what some would call the biggest coup in soft drink history. Clements and his Dr Pepper executives, representing an easy-going beverage which had stayed home in Texas and minded its own business for 85 years, headed over to the 34th Street offices of Coca-Cola Bottling Company of New York, the world’s largest distributor of soft drink’s Goliath: Coca-Cola. Objective: to convince Coca-Cola of New York to bottle Dr Pepper, load it on Coke trucks and sell America’s “most misunderstood” soft drink to 20 million New Yorkers.

Earlier that morning Coke of New York Chairman Charles Millard closed the door of his two-story colonial home in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, started his gray Cadillac, and headed toward Manhattan, where three and one-half hours later he would meet with Clements. During Millard’s 40-minute drive along Route 4, across the George Washington Bridge and down East River Drive, he thought about what Clements could say that would make the outcome of this meeting any different from other soft drink companies that had courted Coke of New York, and failed. He was skeptical about Clements and his Dallas-based soft drink company, and decided that this day his attitude would be the same as before – a “show me” position.

At 11 a.m. Millard and his seven executives entered the penthouse board room of Coke, followed by Clements and his four assistants. They gathered around Coke’s board room table and for three hours listened to Clements explain why Coca-Cola Bottling of New York should distribute a funny tasting soft drink Time magazine once labeled the “Likable Lilliputian.” Clements guided Coke executives through an impressive visual presentation outlining Dr Pepper’s excellent track record of small but impressive footholds in other northern markets. He told them how Dr Pepper was willing to invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in New York and was willing to stick to it through the years to convince New Yorkers that Dr Pepper was a unique soft drink. If he could just get it down their throats, Clements said, he could make them like it. Clements, Millard thought, is one of the best salesmen he’s ever seen. One of the best in America.

Seven months later Millard and Clements shook hands. New York Coke would bottle Dr Pepper. After 85 years Dr Pepper hit the big time, beginning a fascinating David and Goliath battle that in five years has brought Dr Pepper headlines in Time, Newsweek and Fortune magazines, and stirred the ire of Coca-Cola, whose dominance of the soft drink market is even greater than General Motors’ dominance of the auto industry.

Today Clements sits back in his spacious office in Dr Pepper’s national headquarters on Mockingbird Lane, sips a hot Dr Pepper and reluctantly talks about the gains since that portentous day in Manhattan. “Today we have about 200 Coke bottlers selling Dr Pepper, at least 200 7-Up bottlers and about 170 Pepsi bottlers signed up.” The reason Clements doesn’t like to talk about the gains is simple diplomacy – he doesn’t want to rub salt into the corporate wounds of America’s three soft drink giants, which are standing by, watching their own bottlers sell Clements’ Dr Pepper.

Clements and Dr Pepper used a masterful technique to load Dr Peppers on Coke, Pepsi and 7-Up trucks, exploiting the network of independent bottlers which is the mainstay of the soft drink industry. Parent companies like Coke or Pepsi produce only the concentrate, which when mixed with carbonated water, becomes a bottle of Coke or Pepsi. The parent companies make money by selling that concentrate to networks of independent businessmen across America (there are 2600 bottlers), who with their own money have built bottling plants and purchased fleets of trucks. The independent bottler mixes the beverage, bottles it, sells the soft drink to local supermarkets, and stocks vending machines. So the key to soft drink marketing is the local independent bottler, who has a franchise agreement with Coke, for instance, to be the only company bottling Coca-Cola within a certain geographical territory.

In the mid-60’s Dr Pepper managed to get itself declared a “non-cola” by both the Food and Drug Administration and a U.S. District Court, which meant that local independent bottlers franchised to sell Coke or Pepsi, but forbidden by agreement to sell other “colas,” could sell Dr Pepper. (Cola products are derived from the kola nut; Dr Pepper is not.) Dr Pepper, which had spent years selling only in the South, managed to “piggyback” itself onto networks of independent bottlers that Coke and Pepsi had nurtured for years.

“I don’t like the word ’piggyback,’” snaps Clements. “Pepsi started calling it that. I prefer to say we’re distributed by multi-brand operators.”

Multi-brand operators or not, Dr Pepper’s invasion of Coke’s independent bottlers didn’t go unnoticed at Coke’s parent company headquarters, 310 North Avenue, Atlanta. Amidst Dr Pepper’s campaign to sign up Coke bottlers came the New York coup, followed two years later by Dr Pepper’s signing, in Mother Coke’s backyard, of Coke’s independent Atlanta bottler. Now the Coca-Cola parent company would take guests through the Atlanta bottling works and find themselves walking along halls bedecked with Dr Pepper signs. That was too much.

Imagine! A little company called Dr Pepper, with profits amounting to about one-twentieth of Coke’s, hanging out its shingle on the Coke bottler’s plant in Atlanta, two miles from the world headquarters of the Coca-Cola Company. That is the world headquarters of Coca-Cola, which sold 40 per cent of the soft drinks consumed last year in the United States, and whose advertising budget in 1974, at $135 million, exceeded the net sales of Dr Pepper, at $128 million.

“What Dr Pepper doesn’t understand,” suggests an Atlanta observer, “is the insult involved. What Dr Pepper has done to Coke is something you just don’t do to Coca-Cola – at least that’s the way Coke views things.” “Dr Pepper has just got those people at Coke so furious it’s unbeadds an Atlanta-based in-dustry observer. And one Atlanta trade publication correspondent, who talks frequently with the people at Coke, goes so far as to suggest that Coke has grimly pledged itself to a no-holds-barred vendetta against its still small (five per cent of the U.S. market) Dallas competitor.

Adding to the insult was Dr Pepper’s foray two years ago into Japan, a market that in 1973 produced 19 per cent of Coke’s worldwide profits. Dr Pepper signed a joint venture, with yes, you guessed it, Tokyo Coca-Cola Bottling Company, to introduce Dr Pepper to Japan. Timing was awful, as it turned out, because 1974’s skyrocketing sugar prices put the lid on growing soft drink revenues. Rumor has it that so far Dr Pepper has sunk $250,000 into Japan, and Clements declares “we expect to absorb losses there for several more years, and we are prepared to take them.”

“Jumping into Japan was like waving a red flag,” says Richard McStay, formerly research director at Atlanta’s M. Irby & Co., a securities firm. “To Coke, Japan is motherhood, virginity, apple pie or anything you want to call it. All along Coke had been saying, ’Don’t mess with Japan, fellows.’”

While Dr Pepper was busy signing up Coke bottlers, Coke was busy concocting a brand new soft drink made of herbs, spices and fruit juices, plus the obligatory ingredients of sugar, carbonated water and caramel coloring. The drink, which tasted remarkably like Dr Pepper, was named Mr. PiBB, an obvious effort to stem the rising tide of Dr Pepper’s national sales. (Back when Dr Pepper was content with regional marketing Coke tried twice to introduce a competitor. Both drinks, Texas Stepper and Chime, failed about 1960 after some small-scale Texas test marketing.) Announced in late June, 1972, Mr. PiBB’s purpose was to offer a product similar to Dr Pepper which Coke bottlers could sell to the “Dr Pepper taste market” without actually selling Dr Pepper. Now those Coke bottlers who had defected to Dr Pepper could return to a line of all Coca-Cola products.

Predictably, Coke discouraged any thoughts that Mr. PiBB was aimed at Dr Pepper. “I haven’t tasted Dr Pepper myself,” said a Coke spokesman blandly, “so I wouldn’t know how similar Mr. PiBB is to it. I don’t think it was meant to compete with Dr Pepper – as far as I know Coke just felt there was a market for this kind of soft drink.”

Curiously enough Coke decided to test its new soft drink in Waco, birthplace of Dr Pepper, where more Dr Peppers are consumed than any other drink. Other test markets included Temple, Texarkana, and three Mississippi towns – West Point, Starkville and Columbus – all areas of Dr Pepper’s small town Southern strength. Coke’s motive was to test Mr. PiBB in areas where consumers had already acquired a taste for Dr Pepper, to see if Mr. PiBB could make it toe-to-toe with Dr Pepper.

Clements grins at the mention of Mr. PiBB as competition. “I don’t suppose they like to hear me say this in Atlanta,” he says, “but Mr. PiBB has just stimulated the taste for Dr Pepper. In fact, we’ve found that whenever they quit giving it away in big promotions their share of the market drops way down.”

Asked about Coke’s testing of Mr. PiBB in Dr Pepper sanctuaries like Waco, Clements coolly replies: “I had all their marketing plans and test locations in hand eight weeks before they even started. It didn’t change our strategy a bit.”

Clements’ aplomb is well justified, at least for the moment, as Coke really isn’t ready to take on Dr Pepper from coast to coast. Coke distributes Mr. PiBB through only 300 of its 850 U.S. bottlers, primarily in areas where Dr Pepper is strong. “If Pepsi or some other bottler is selling Dr Pepper in an area,” says a Coke distributor, “the Coke bottler won’t necessarily take on Mr. PiBB. Now if Dr Pepper starts gaining strength, the Coke bottler might want to add PiBB so he can head off Dr Pepper. You just don’t want Dr Pepper to get out of hand.”

Dr Pepper is growing, having passed Royal Crown Cola in 1972 as the nation’s fourth largest soft drink, and now Clements talks of overtaking number three, 7-Up. Coca-Cola is first, by a wide margin, followed by Pepsi-Cola. Mr. PiBB is hardly a threat to Dr Pepper. It hasn’t cracked into the top ten selling brands yet, and in none of its markets has PiBB gained more than three per cent of the area’s sales.

But Coke has challenged Dr Pepper here and there, in an effort to reverse some of Dr Pepper’s inroads with Coke bottlers. Coca-Cola isn’t about to stand up and boast about its arm twisting technique, but the evidence exists that Coke applies some “persuasion” to a few bottlers just to let Dr Pepper know that Coke still cares. First to crack was the Coke bottler in Rochester, which suddenly dropped Dr Pepper a year ago in favor of Mr. PiBB. Next to switch were bottlers in Atlanta and Miami, which doesn’t suggest a landslide to PiBB, but does suggest something more than coincidence at work.

Just what kind of persuasion Coke put on the three bottlers isn’t clear. Independent Coke bottlers can have their franchises revoked for only three reasons: insolvency; failure to promote Coke products aggressively; and failure to maintain the quality of Coke products in the mixing process. Coke can’t simply threaten to revoke the bottling franchise because an independent bottler decides he’d like to sell Dr Pepper.

“What Coke can do,” says a businessman who owns both Coke and Dr Pepper franchises, “is not be quite as helpful as it might ordinarily be. The parent Coca-Cola Company has marvelous expertise in marketing and promotion, and it might just decide to ignore you a little bit.” Clements terms the Atlanta defection to Mr. PiBB “an emotional decision rather than a business decision. The parent Coke company and its Atlanta bottler have close personal ties and let’s face it, the situation did become confusing. Most people think Coke’s parent company owns the Atlanta bottler, which was bottling Dr Pepper.”

Dr Pepper wasn’t damaged badly by the Atlanta switch, because it trotted over to the Atlanta Pepsi bottler, who was more than happy to sell Dr Pepper. “We might have been hurt from an ego standpoint,” says Clements, “but over a lifetime, the Pepsi bottler in Atlanta probably will do a better job for us,” he says. “The Coke bottler was handicapped by emotional ties and wouldn’t have promoted Dr Pepper aggressively.” The Pepsi bottler is owned by General Cinema Corporation, and is out to make money selling anybody’s soft drink. When the Miami Coke bottler dropped Dr Pepper, Clements turned again to General Cinema, which also owns the Pepsi bottling plant in Miami.

Indeed Dr Pepper appears to have the upper hand in many of these situations, as one analyst explains. “If a Coke bottler drops Dr Pepper for Mr. PiBB, he knows that Dr Pepper will walk across the street and sign up with Pepsi or 7-Up. But if the Coke bottler keeps Dr Pepper, he knows Coca-Cola won’t sell the Mr. PiBB franchise to Pepsi or 7-Up. By keeping Dr Pepper, he’s keeping an established soft drink which will have the market all to itself.”

The thought of Dr Pepper testing Coca-Cola’s patience seems almost comic, because the Coca-Cola brand alone sells 28 per cent of the world’s soft drinks, compared to Dr Pepper’s five per cent share. Throw in Coca-Cola Company’s three other major soft drinks, Sprite, Tab and Fresca, and nearly one in every three soft drinks consumed is produced by the Coca-Cola Co.

Oddly enough, Coke became the soft drink giant while Dr Pepper, one year older than Coke, slept peacefully in its native South since 1885. Dr Pepper had its beginnings in Waco’s old Corner Drug Store, where a soda jerk, whose name has been lost to history, concocted a popular drink. The soda jerk married the daughter of a physician, the story goes, who wasn’t pleased with his daughter’s marriage to such an insignificant character. The young man tried flattering his disapproving father-in-law, Dr. Pepper, by naming the fountain drink in the doctor’s honor. The soda jerk later sold this formula to a Waco chemist named Robert Lazenby, who founded the Dr Pepper Company. No one knows what happened to the soda jerk or his father-in-law, Dr. Pepper.

Dr Pepper slowly but surely spread throughout the South during the 20th century, while Coca-Cola established a vast network of bottlers nationwide, producing many a millionaire, which is part of the irony of the Dr Pepper-Coke battle. Dr Pepper sat around for 75 years watching Coke set up the bottling network, then Dr Pepper stepped in and used the Coke bottling network to distribute itself, coast to coast.

Clements, 61, spent much of his 40 years with Dr Pepper watching the company sit back and let the world, and Coke, go by. An Alabama native, Clements financed his college education by digging ditches for the WPA, sweeping dorms, cutting meat in a supermarket, operating a cafe (the Sugar Bowl) and working as a part time Dr Pepper route salesman. Clements rose through the company ranks, coming to Dallas as a junior executive, but quit in disgust in 1949.

“The company didn’t have any leadership,” he says, “and it wasn’t going anywhere. There were no signs of any changes, so I agreed to become a partner in the Roanoke, Virginia, Dr Pepper bottling plant. I gave the Dallas company three months notice, but before I left, Leonard Green was named president of Dr Pepper. I had to go on to Roanoke but Green telephoned me practically every night in Roanoke until I decided to come back.” Clements rose through the marketing ranks at Dr Pepper, becoming very influential in some critical decisions of the 1960s. The company decided to abandon its low calorie Swedish imported soft drink, Pommac, and also dropped its ice cream topping. The company retained its fruit flavors, Salute, as a courtesy to bottlers, and also kept Hustle, its high protein drink, to protect the name in case the high protein market becomes important. Most significantly, Clements guided the company out of its contentment with a regional product and into a full blown national marketing program, concentrating on Dr Pepper alone. In 1970 Clements was named chief executive of the company.

Today Clements relaxes in his new office, pleased to spread the word about his favorite subject. “No, I don’t grow tired of talking about Dr Pepper,” he says, “because I think that’s what keeps our people here so happy – the challenge of selling Dr Pepper.” Clements’ day is punctuated by Dr Pepper – four hot ones in the morning and a half-dozen cold ones in the afternoon – “unless I move around a lot and work up a thirst – then I drink more,” he says. Between Dr Peppers he fires up Travis Club cigars.

“Dr Pepper isn’t a good name because it doesn’t sound like a soft drink.” Clements explains, “It’s not a cola or a lemon-lime drink, so you can’t describe its taste. Now that’s the challenge, just getting it down people’s throats a few times. If we can do that they’ll keep coming back for more.”

Clements’ tenure as president and board chairman has been successful – the company’s revenues and profits have increased steadily except for 1974, when the sugar shortage stymied the entire soft drink industry. His performance and that of other top Dr Pepper executives have been rewarded generously through the company’s stock options. Although Clements’ 1974 salary was a respectable $104,000, during the last several years he has exercised options for 60,000 shares of Dr Pepper common stock, worth far more than his salary. The stock, purchased for $510,000 had a market value of $1,267,000.

Some think Dr Pepper’s glory days are over, days when $10,000 worth of its stock ballooned to $350,000 worth in a mere ten years. Days when Dr Pepper’s growth was at least as good as Coca-Cola’s and generally better, two or three times the soft drink industry’s average. Growth caused by adding Coke, Pepsi, 7-Up or Royal Crown bottlers to the Dr Pepper network. But that phenomenal expansion ended last year when Dr Pepper added bottlers in Altoona and Potts-ville, Pennsylvania, and one in Presque Isle, Maine, completing the company’s coast-to-coast distribution network.

Now the Dr Pepper genius must shift to battling Coke and others not at the bottler’s plant, but in the supermarket. “The supermarket is a very, very tough marketplace,” says Memphis analyst Richard McStay. “It’s a slow, knockdown, drag-out, beat-on-the-door type process. You don’t, do it overnight.”

Clements describes the old Dr Pepper marketing strategy as a guerrilla-like surround-the-cities battle plan. “For years Dr Pepper has been strong in small towns. We’d gain our strength in small, outlying areas and then invade the big city market. But now we’re hitting the big cities, trying to get more supermarket shelf space.”

If the gamesmanship of signing up Coke’s bottlers was exciting, the battle to snatch a few feet from another soft drink’s supermarket shelf space is a real thriller. “Basically supermarKets allocate space to soft drinks ac-cording to how well they sell,” Clements says. “To grow you’ve got to convince the store to give you more space than you really deserve.” And of course the kicker here is that getting more space than you deserve means beating a competitor out of some of his space – not exactly a passive game.

“We’ve worked very hard at developing personal relationships with supermarkets,” Clements explains, “so we can get the shelf space we need. I think Dr Pepper is particularly effective at this sort of thing – edging the bigger companies out of some shelf space.”

The game is played at several different levels, with top executives like Clements making a point to visit supermarket conventions and sell Dr Pepper to the chains’ top executives. Bottlers have “home market managers” who head up a staff which concentrates on supermarket district managers and even individual store managers. “There is a constant battle in the supermarket for shelf space,” says the marketing vice president of one North Texas bottler. “And unfortunately the game often becomes one of personal relationships.”

Says an independent Dr Pepper bottler: “There’s all sorts of different ways to get more shelf space. We provide promotional gimmicks for the stores, offer to replace worn out shelves and so forth. Sometimes it just gets down to a route salesman knowing how to handle a particular store manager, convincing him to give you a little more space at someone else’s expense. You’d better do it right though, because that someone else isn’t going to like it.”

“The first thing I look for is service,” says a Dallas Safeway store manager. “I want the soft drink salesmen to come in here and stock my shelves quickly, neatly and the way I want it done. I want them to clean up in the area and stock my vending machines. The guy who does that might get a little better shelf space.” Like any other kind of politics, the shelf space game involves a you-scratch-my-backscratch-yours principle. Safeway store managers are paid a salary plus a semi-annual bonus based on the individual store’s profits. The manager of a low volume Safeway store might make two or three thousand annuallv from bonuses, but managers of the best stores in town might make close to $10,000 from bonuses.

“Recently Dr Pepper sent a couple of guys out here to repaint my soft drink shelf space,” another Safeway manager said. “Not only that, they had two guys out here for three days helping remodel the backroom storage area. If they hadn’t done it I would have hired someone to do the work, so it saved me salaries, which makes my store more profitable.” When the soft drinks were put back on the shelf, Dr Pepper had replaced Coke in the best spot – the first drink you see when turning out of the high-traffic outside vegetable aisle.

Not all chains give managers a free hand in laying out soft drink space. Kroger, for instance, specifies the general layout of its stores’ soft drink areas. “Of course we can ’adjust’ our soft drink shelf space, you know,” says a Kroger manager. “I make adjustments based on service, attitude of the salesman, and personality. Personality is very important.” If the Kroger manager wants to remodel his soft drink shelves, he asks a soft drink salesman to do it, and says he’ll return the favor by giving the drink a better position or more space.

The supermarket game also extends to special promotions. The major soft drink bottlers are constantly offering supermarket chains promotional deals, which each chain usually runs about twice a month, a week at a time. Each chain chooses whatever promotion looks best – rarely are two soft drinks being promoted at once. The game here is to get supermarkets to accept your promotions more often than your competitors’, and that involves its fair share of “salesmanship.”

The smaller soft drink companies, like Dr Pepper, do well to play the sales game, because they’re trying to grow by getting more shelf space. To Coca-Cola the sales game is one of self-defense. “Sure, we play the game too,” says a Coke bottler. “But really we’d be better off settling for space based solely on sales volume, because we are the largest and we’d have plenty of shelf space without having to wrestle for a little more.”

While Dr Pepper wages war in the supermarkets it must protect its recent gains, some of which bear watching. The Japan venture hasn’t been exactly an overnight success, and Dr Pepper must be willing to hang in there, something Clements is determined to do. Currently Coca-Cola has 55 per cent of the Japanese market and Pepsi has eight per cent, while Dr Pepper, according to a report it filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, has “a negligible” amount of the Japanese market – the most important foreign market to U.S. soft drink manufacturers. Always optimistic, Clements says, “We think that once Japan gets through its inflation problems Dr Pepper is going to do great there.”

The New York picture isn’t exactly rosy either, leaving Dr Pepper’s plans for a profit in three years looking more like a profit, maybe, in six years. Competitors estimate Dr Pepper and the New York Coke bottler spent a million dollars promoting Dr Pepper’s entry into the New York market, driving Dr Pepper sales up to a remarkable five bottles a year for every man, woman and child in the New York metropolitan area. But then along came a price war with Pepsi, followed by a bottler strike in the Coke bottler’s New Jersey operation, leaving Dr Pepper’s bottler, Coke of New York, short of cash.

“Dr Pepper had the most successful introduction in New York soft drink history,” says Coke’s Millard. “It went through the normal post-introduction decline and then the doubling of sugar prices hit. I think the sugar situation is about over. Dr Pepper has a small, but respectable share of the New York market.” Coke of New York has since added its second product outside of the Coca-Cola line, Welch’s Sparkling Grape Soda. “The Dr Pepper experience opened our eyes to other opportunities,” Millard says, “and it also showed other soft drink manufacturers what we can do here.”

And, too, there is an action by the Federal Trade Commission pending against Dr Pepper and every other major soft drink company. The FTC claims franchising only one bottler in a specific territory is anti-competitive, and Clements admits that if the FTC wins, the bottling industry will be in “chaos.” It will be particularly rough on small companies like Dr Pepper, Clements says, predicting that corporate giants will take over regional bottling from independent businessmen and forget about the little accounts, like a Dr Pepper vending machine in a little beauty parlor. “Our willingness to sell anywhere has been bread and butter to Dr Pepper,” he says, “and we need those little accounts.” Fortunately for Dr Pepper, so far only Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola have had to defend the industry in costly court proceedings, because the FTC examiner decided to base his decision on cases against the two largest soft drink manufacturers. “But I should say that we’ve spent plenty of money just waiting in the wings,” Clements says, adding that he has testified on behalf of both Coke and Pepsi.

Perhaps the most immediate difficulty facing Dr Pepper is its earnings. For nearly a decade Dr Pepper executives have been predicting to the point of monotony annual sales and earnings increases of 15 per cent. The predictions became a litany for them, and buoyed along by their yearly success, executives began to see the predictions as self-fulfilling prophesies. But last year the company’s net earnings, 52 cents a share, were only a penny per-share higher than 1973. During the first half of 1975, Dr Pepper’s per-share earnings, 16 cents, are down two cents from 1974’s disappointing year. Dr Pepper’s glamour days may not be over, but for the moment they are stalled.

Clements’ optimism is so great he doesn’t even want his people to think about negative things analysts might say, much less read about them. “I’ve asked my people to quit reading the newspaper, to quit reading the business magazines,” he says. “I don’t read Time, I don’t read Newsweek, I don’t read any of those magazines. I just want them to read Sports Afield, Sports Illustrated and Playboy. I don’t want their minds cluttered with negative things.”

Instead of “negative” talk about Dr Pepper, Clements furnishes his people with a sincere optimism leading to statements some would call downright grandiose, while others would consider them what they really are – spreading the gospel of Dr Pepper. “Once you drink Dr Pepper regularly,” Clements says, “nothing else satisfies your taste. You might drink something else occasionally, but you’ll find yourself gravitating back to Dr Pepper.” Does Clements have any data substantiating his claim that Dr Pepper has a mystical holding power over the world’s thirsts? Yes, he does, Clements responds, but he doesn’t intend to make any of it public. “I don’t care whether I convince anybody or not. I’m more concerned about convincing the Dr Pepper staff about what we are going to do and then doing it, and letting ever3’body else learn about it.”

Clements’ predictions for conquering the world’s soft drink market are unabashedly frank. “Right now we’re second in the Dallas market, but I’d say by 1977, or maybe a bit sooner, we’ll be number one,” he says. And what about overtaking Coke in the United States? “Well, I’ve never put a date on it before,” he says, “but don’t forget Coke completed its U.S. distribution system in 1922 and we didn’t finish ours until 1972, so they’ve had a big lead. But I’d say we ought to outsell Coke in about 25 years.”

That’s a mighty big prediction for the testy soft drink company at Greenville and Mockingbird, something like Gremlin telling Chevrolet to move over. Dr Pepper’s performance so far has been nothing short of amazing, so one might be inclined to give Clements the benefit of the doubt. But the blitzkrieg invasion of Coke, Pepsi and 7-Up bottlers is over, and now Dr Pepper must hold its own and also fight it out toe-to-toe with the big boys in the supermarket. Whipping Coke at Safeway, Tom Thumb and Kroger is a tall order for a small company.

So why bother? Why not be happywith Dr Pepper’s current gains instead of pressing onward in search ofmore? It’s not because Clements orthe folks at Dr Pepper have anythingagainst Coke, but instead selling DrPepper is a moral duty. Smiling as hesips a hot Dr Pepper, Clements says,”When you’ve got something as goodas Dr Pepper, everybody ought tohave a chance to enjoy it.”

Our First Annual Soft Drink Tasting

The man at Coke says he’s never tasted Dr Pepper. The man at Dr Pepper scoffs at the mimicry of Mr. PiBB. The Pepsi people say that most Coke drinkers actually prefer Pepsi.Whom can you believe?

In the great consumer interest, D set out to test and report conclusively the recognizability of soft drinks. Even the best laid plans . ..

A panel of eleven judges was carefully selected; most were chosen for a general affinity for soft drinks; at the extremes, a balance was attained between a couple of self-proclaimed soft drink connoisseurs and a couple of self-pronounced soft drink deprecators. There was also a reasonable balance of Dr Pepper fans, Coke fans, etc. The perfect panel, a model of impartiality. And a picture of self-confidence – “This’ll be a snap,” was the prevailing mood.

The taste was on. In Phase One, four unmarked containers were filled with the carbonated contestants: Coke, Pepsi, Dr Pepper, Mr. PiBB. The first judge poured a few ounces of drink A into his glass. He swished the liquid around as he held it to the light. “Marvelous body,” he murmured. Then, closing his eyes, he sniffed the half-filled glass. “Magnificent bouquet.”

Judge number two appeared slightly intimidated by number one’s arrogance. He, too, swirled the drink around in his glass as he held it to the light. He spilled most of it down his arm.

When the sampling was over and each of the eleven had written down his identifications, the results were tabulated. The panel’s cocky attitude proved well-founded. Eight scores were perfect; two judges confused PiBB and Pepper. One judge, however, saw his respectability shattered as he identified Coke as Dr Pepper, Dr Pepper as Mr. PiBB, and Mr. PiBB as Coke. To his great credit, he identified Pepsi, his favorite drink, as Pepsi.

CONCLUSIONS: 1) Coke and Pepsi are easily distinguished from each other. 2) Dr Pepper and Mr. PiBB are distinguishable but less easily identified (thisdetermined from the frequency ofscratch-outs and second guesses in thosetwo columns of the ballot sheets), probably due to unfamiliarity with Mr.PiBB and, to some extent, Dr Pepper. 3) One of the eleven judges was a dolt.

While the other ten judges were still snickering at the eleventh, Phase Two of the tasting was announced: only the containers with Dr Pepper and Mr. PiBB were left on the official table. Judges were asked to taste each, identify them correctly, and describe the tastes as best they could.

As the tasting began, there was a noticeable change in mood – the cool cockiness was changing to consternation as the judges were seen to be returning often to the table for additional samples. The results were disastrous: of the eleven, only three correctly identified the two drinks. The judges were staggered – one demanded a recount, another pulled out a cold beer and told the head judge where he could put his contest.

The commentaries on the tastes resembled the various eyewitness accounts of an accident. One judge wrote that Dr Pepper had “a strong cherry taste,” another claimed that it had “less of a cherry taste.” Three panelists said that Dr Pepper was more carbonated, but another complained that Dr Pepper “does not fizz good.” One judge tasted Mr. PiBB and wrote, “This one is Dr Pepper. I’ve been drinking it for years and nothing can touch it.” An obvious Dr Pepper connoisseur correctly identified Mr. PiBB and said, “A miserable imposter. Tastes like Cragmont Black Cherry Cola that’s been sitting out in the sun for two days. Disgusting.” Other enlightened commentary included such discriminating judgement as “blah” and “would taste good with fried pork-skins.” The last ballot was submitted by a judge who had returned to the tasting table numerous times and finally wrote, “I feel like I did when I was ten years old and ate a whole bag of marshmal-lows.”

CONCLUSIONS: 1) The results of Phase One are highly suspect. 2) Carbonated beverages can destroy taste buds and produce queasiness. 3) Eight of the eleven judges were dolts. 4) Taste tests are ridiculous.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte