Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

Daniel American Horse, all 6 feet 6 inches of him, has just returned from the liquor store down the street, clutching a fifth of cheap red wine. He saunters over to our booth in the darkness of Tom & Jerry’s Lounge, sits down beside his companion, Newton Prentiss, and swigs ferociously from the bottle.

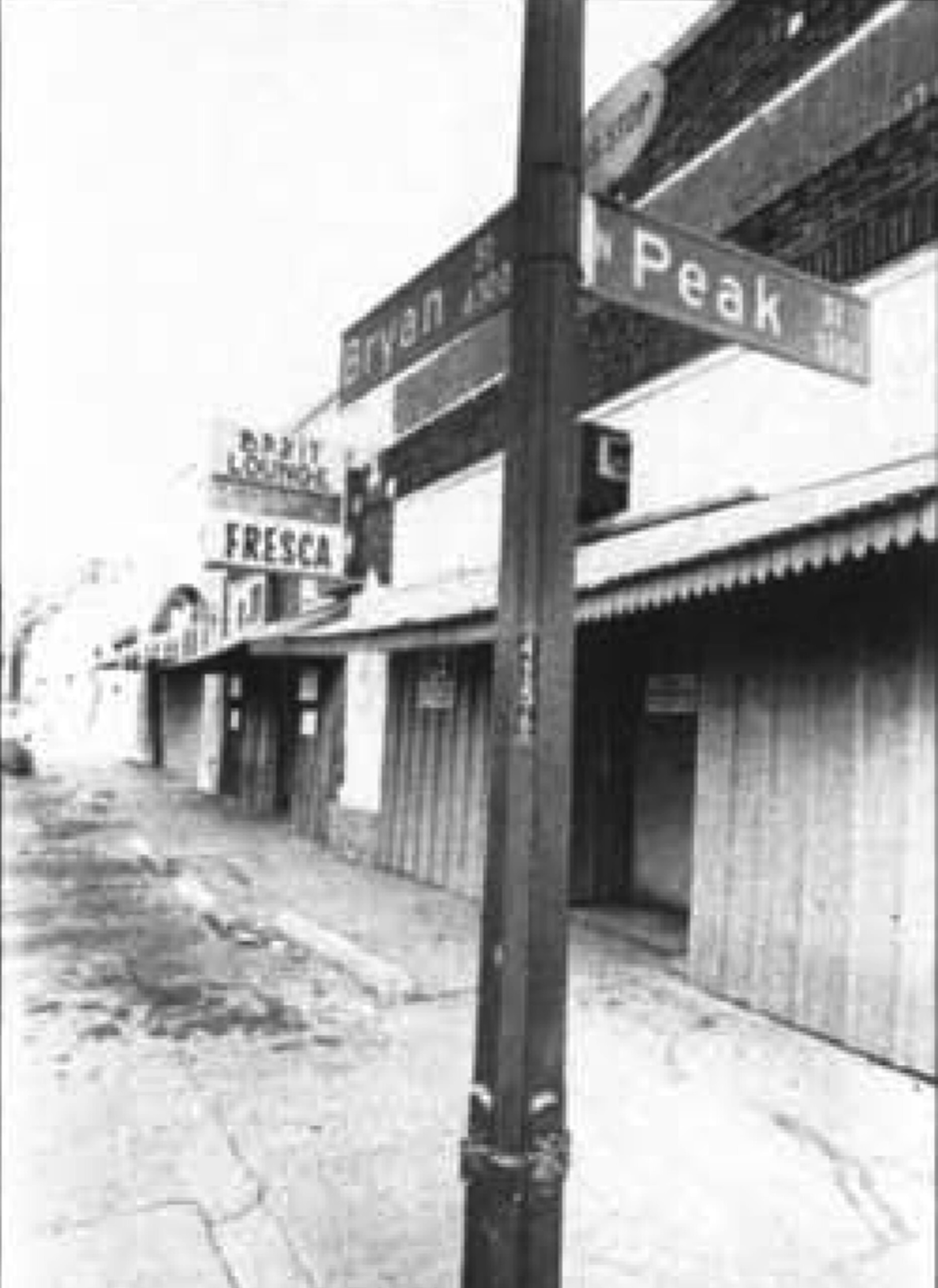

In a quiet voice, he explains he was on his way to California when the alternator on a friend’s car went out, and now he must stay in Dallas until he makes enough money to get it repaired. He passes the bottle to Newton, an Oklahoman who must weigh close to 300 pounds. Newton’s long black hair is braided with red felt ribbon, and atop his head is a black, round-top hat — like Hopalong Cassidy’s except black — with a red bandana hatband. Carrying a backpack that holds all his belongings, he hitchhiked to Dallas to look for work. As long as they’re in Dallas, the two men will spend most of their evenings and some of their days at Tom & Jerry’s near the intersection of Peak and Bryan in East Dallas.

Newton Prentiss is a 31-year-old Kiowa Indian; Daniel American Horse is a Sioux from Montana; The Corner — Peak and Bryan, that is — is all they have to call home these days.

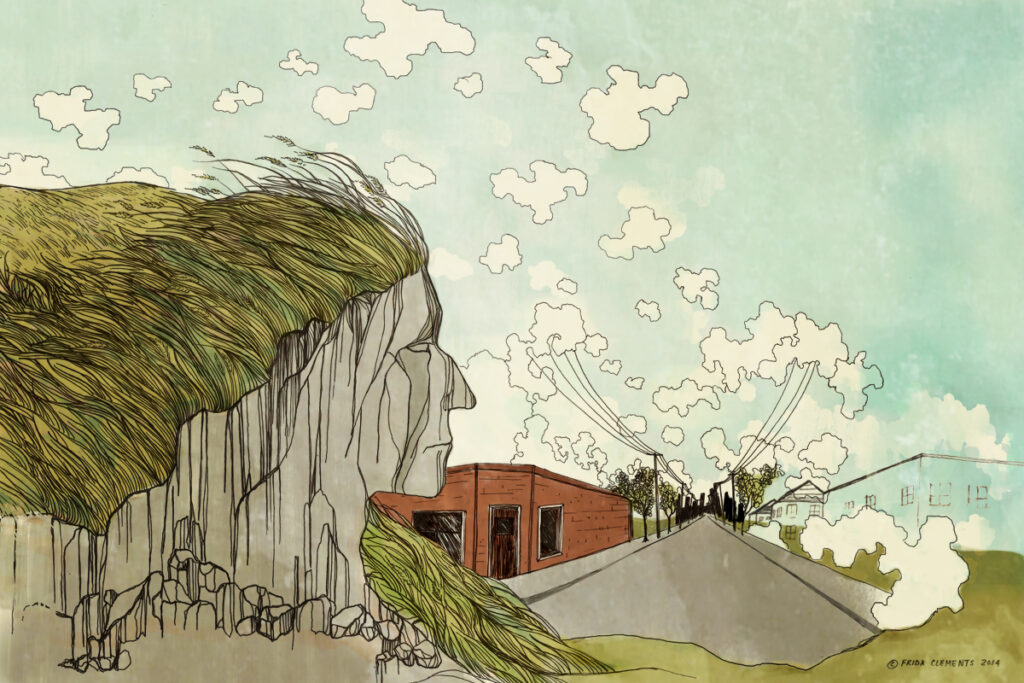

It is home to thousands of other Indians too, their own little Cement Prairie, as many of them call it. Here amongst the squalid bars and rooming houses of deep East Dallas, some 2,000 American Indians a year get their first taste of life in the big city.

The Corner is at first glance a cluster of depressing, ramshackle bars on Bryan. But for the Indian coming into Dallas to live or perhaps to work for a few months, The Corner is more than just an alcohol oasis. Most likely he has heard about The Corner before leaving home. He knows it is where he can find other Indians, brothers and sisters who have learned to survive in the strange, cold city. The Corner becomes his starting point, and the Indians who congregate there become his guides, as he begins his foray into the heart of the white man’s world.

Wayne Hunter, a tall, poker-faced Cheyenne from North Dakota, sits down at our booth.

“Indians all over the country know about The Corner,” he says. “Like I came to Dallas about this time last year from San Diego. I never had been here in my life, didn’t know nobody. See, us Indians like to stick together. So when I got off at the bus station, I asked a man where I could find some Indians. He said go to Peak and Bryan. So I got on a city bus and told the driver to tell me where to get off. He let me off down there at the Rainbow [another Indian bar], and just when I turned the corner I ran into three guys I grew up with in North Dakota. Hadn’t seen ’em in 10 years at least.”

Wayne, at 28, has lived all over. He is articulate (before the alcohol takes control), apparently educated, and he claims to have run a federally-funded Indian Center in Denver for a while. He’s enrolled in welding school, and he plays a little basketball now and then, but most of the time he sits quietly over a glass of beer in T & J’s.

Daniel empties the wine bottle and goes back to his beer, a faint smile on his face, his eyes bloodshot. We have talked through two pitchers of beer when a strikingly attractive young woman in a lime-green dress and high heels swirls through the door. Nema, she is called, but no one seems to know her. She clowns through a game of pool with Perry, a middle-aged fellow so drunk he frequently lurches into the table. When the game is finished, both squeeze in the booth beside me.

“Here to write about all the drunk Indians, right?” Nema challenges, deftly pinning me to the wall in two ways.

After a little coaxing, she begins telling me about growing up in Oklahoma City. Perry keeps interrupting, wanting to be interviewed; his mind is alcohol-addled, and his speech slurs into incoherence.

Nema is getting peeved at Perry, and Perry is getting jealous. He flashes a malevolent grin my way, and mutters, “Yatahe.” That word I understand. It is Navajo for “let’s fight.”

Perry staggers up from the table with a baseball-bat grip on the pool cue. Quickly, mercifully, Daniel and Newton intervene and steer him back to the pool table, where he aims the stick at a white cue ball instead of me.

Meanwhile Nema is getting suspicious. “Let me see your magazine,” she demands, snatching away the copy I have with me. She takes it to a man in white shirt and tie at the bar, and they thumb through it. Twenty minutes later she tosses the magazine on the table in front of me. “There’s nothing about Indians in here,” she says. “I’m not saying another word to you.”

A few minutes later a white-haired, grandmotherly lady pushes open the front door and strides briskly back toward the bar. “Hi, Mom,” people yell, and Mom waves and slaps a few shoulders on her way to the bar. Mom — her real name is Lida Stultz, but few people know it — owns Tom and Jerry’s. For 18 years she’s been on The Corner, all that time running an Indian bar.

Mom curses with the best of them, likes a dirty joke as well as the next man, and attends church every Sunday. “I’m the one who opened the Indian house up on The Corner,” she says, sitting behind her desk in the cluttered back room that serves as her office. Beside her desk is a large glass terrarium. It contains a huge stuffed rattlesnake, fangs bared, forever coiled to strike.

“The Indians came to me and said, ’Mom, we want a place of our own where nobody’ll bother us.’ I said okay ’cause nobody else would cater to ’em; they was all afraid of ’em.

“I took ’em in when they come off the reservation. When they first come here most of ’em didn’t know any English, they wouldn’t know how to use the laundromats, they didn’t know anything about livin’ in the city. I helped raise ’em up, and now those same people’s children are comin’ in here.”

In deep East Dallas, thousands of Indians get their first taste of city life.

Four years ago Mom had to move off the corner of Peak and Bryan to her present location a few blocks away. “That little judge who retired here while back, Judge Lew Sterrett, he said there were too many Indians over there, they was causin’ too much trouble, and costin’ the taxpayer too much money. So he told the police if they moved Mom out, the Indians would move out too, would sorta scatter, you know. So I got word that if I didn’t move off The Corner the judge would make sure the Liquor Control Board didn’t renew my license. So that’s how I ended up here.

“We don’t have much trouble as long as the n*****s and Meskins stay out. I don’t have anything against ’em, but when they come in, I tell ’em this is an Indian house, and they don’t belong here. Just the other day this nice-lookin’ n***** gal came in and sat down. I told her she better leave before she got in trouble, and she told me right off she was a Comanche, said her husband was a Comanche from Oklahoma, and her children were, too. I told her, ’I never saw no kinky-haired Comanche like you,’ so she said if I’d call a taxi for her, she’d leave.”

Indians have always lived in Dallas, but they began coming in sizeable numbers in the late ’50s, about the time Mom opened her bar. The Bureau of Indian Affairs set up a Field Employment Assistance Office in Dallas in 1957 to administer what was then called the Relocation Program. The program was aimed at encouraging Indians to move off the less promising reservations and into industrial centers where work opportunities were more plentiful. “Relocation” was instituted by Commissioner of Indian Affairs Dillon Myer, who was director of the Relocation Centers where Japanese-Americans were “quarantined” during World War II. The term had disquieting connotations to many Indians from the beginning; nevertheless, thousands have been “relocated” over the years to Dallas and other cities across the nation.

Under the Relocation Program, the BIA helped Indians find jobs, housing, and other basic needs during their first few weeks in the city. When the Indians started coming in to Dallas, the BIA sought cheap housing that was close to downtown and accessible to bus routes. East Dallas — even though some of the available housing approached slum status — met those needs. Indians from as far away as Alaska and as close as Oklahoma started moving in. Although the Relocation Program has been abolished, Indians are still coming to Dallas under the Employment Assistance Act and the Vocational Education Act, and even more are coming on their own. Sizeable Indian communities have also developed in Oak Cliff, the Casa Linda area, and Garland, but it is East Dallas that still draws most of the new arrivals.

Of course, most Indians who come to Dallas don’t stay on The Corner drinking themselves into oblivion. In fact, most are very sensitive about the “drunk Indian” stereotype, while at the same time recognizing that alcoholism is a serious problem among Indians.

The Powells, a young Creek couple from Okmulgee, Oklahoma, are probably typical. They live a few blocks up the street from Tom and Jerry’s in one of the cheaply built, motel-style apartment complexes that have replaced many of the old two-story houses in the Peak and Bryan area.

“I went to The Corner a few times when I first came to Dallas,” Eldean Powell confesses. She glances at Rusty, her husband, and giggles shyly, eyes cast down, hand covering her mouth. “See, I didn’t know anybody, so when I finally met these Indian girls at work, they said we could go to the Rainbow to meet other Indians.”

After a few months in Dallas, Eldean went back to Oklahoma and married Rusty, who was from the same area. They decided to move to Dallas, and Rusty soon found a job with the University Park Parks Department.

The Powells agree that holding on to their Creek heritage is not easy in a city like Dallas. Posters of famous Indians decorate the walls of their small, neat apartment, and Rusty wears his hair pulled back into a pony tail, but “it’s about all the Indian I’ve got,” he says. They can still perform the traditional Creek Stomp Dance, and they know the Creek language, but they rarely use it. “Sometimes when we’re fussing at each other we’ll use Creek words,” Rusty laughs, but the Powells’ 17-month-old daughter Annette will probably never know her tribe’s language.

Growing up in rural Oklahoma, the Powells attended public schools, and Rusty says he never gave much thought to being Indian until an incident in the fourth grade. “My grandmother came to get me out of school one day,” he recalls. “There was an emergency at home, and she had to come pick me up. She had on her long Indian skirt and beads and moccasins like she always wore, and she talked to me in Creek. I remember being ashamed of her because of the way she looked and because she couldn’t speak English.”

Rusty remembers sitting at the feet of his grandmother, who still lives in eastern Oklahoma, and listening to stories she had heard as a young girl about the infamous Trail of Tears and about how the white man cheated the Indian out of his land. When she was a young girl, she told Rusty, Indians in Oklahoma owned a lot of good land. If a white man wanted it, he would toss some money rolled up in a sack on the Indian’s porch. If the Indian opened the front door and picked up the sack to see what it was, that meant he accepted the white man’s offer and had to sell him the land.

To the gang at Tom & Jerry’s, Indian BIA employees and any Indians who cooperate with white schemes to help the Indian are “apples” (red on the outside, white on the inside). “Indians have been pushed around a lot,” Bud Two-Feathers, a T&J’s regular, asserts, “and they’re still gettin’ pushed around. By whites sure, but by their own Indian brothers, too.”

Indian BIA employees and any Indians who cooperate with white schemes to help the Indian are “apples” (red on the outside, white on the inside).

Getting pushed around by white cops is the topic when I wander into Tom & Jerry’s a few days after my first visit. “After you left the other night, American Horse got arrested,” Newton explains. “He and I got a little drunk, and after a while we went out back to sleep it off. We was back in the alley asleep, and these two cops come back there and hauled Daniel off for public drunkenness. He’s s’posed to get out tomorrow, I think. I was layin’ right there beside him, but they didn’t even mess with me.”

Newton and Two-Feathers shake their heads over the inscrutable ways of white police officers. (I suspect the decision might have had something to do with Newton’s massive bulk, but I let the theory pass.) Two Feathers suddenly recalls another incident. “Like one time these two cops come in here and took seven of us outside ’cause we were drunk. Once we got outside they arrested five guys and let two of us go. For no reason. Why would they do something like that? This one cop he says to me, ’now you walk that way,’ and he pointed down the street, and he told my buddy to walk the other way. So we did. I guess he didn’t know we just walked around the block and met up with each other. I can’t figure ’em out.”

“Are there any Indian police officers?” I ask.

A woman sitting with Two Feathers knows of an Indian policeman who works in East Dallas. He helped her force her husband out of the house after she divorced him. No one else knows any Indian policemen.

Someone asks how Roland is, and Newton explains that Roland is a T&J regular who got stabbed in the back at the Rainbow the previous Saturday night. I give Mary the barmaid a quarter, and she calls Parkland; “Fair condition,” she reports.

“That Roland, he’s crazy,” Mary says, shaking her head. “Wayne, you remember last year don’t you when he was sitting in here one night with some gal, and her husband came in here and shot him. You know what he told me when he got out of the hospital? He said, ’Mary, I just wanted to die. That’s all I wanted. I just wanted to die.’”

Later I ask about AIM, but everyone is reluctant to talk. Wayne says he has no use for AIM because they took over his Indian Center in Denver, but Newton gently reprimands him. (“Brother, you’re entitled to your own opinion, but I’ll have to disagree with you there. They’re doin’ a lot of good.”) Mom tells me later that Newton is an AIM organizer from Wounded Knee, but Newton has never told me this, although he did show me an AIM button. Two Feathers says he knows a lot about AIM, but he doesn’t think a white man needs to know about it.

Indians in Dallas and elsewhere have been noticeably absent from most traditional civil rights activities. Indians prefer to work alone. They are not as interested in joining the American mainstream as they are in gaining from Congress, the BIA, and well-meaning whites a cultural agreement to leave them alone. In cities across the nation, Indian-run organizations like the Inter-Tribal Center in Oak Cliff and the American Indian Center in East Dallas are working for self-determination.

Bud Two Feathers, a 36-year-old Shoshone, has a bone to pick with the American Indian Center. He tells us about coming to Dallas last year from California with no money and no job. Four days he spent looking for work he says, and all that time he had nothing to eat. He found out about the American Indian Center, but no one there would help him. The Salvation Army finally gave him a $10 food voucher, and eventually he got a job welding.

I tell him I have an appointment with the director of the American Indian Center for the next day, and I’ll ask her why he couldn’t get help.

“And you’re goin’ to write about what I just told you?” Two Feathers asks, his face lighting up. “And people are gonna read what you put down? And they’ll know how it is, right?”

“I hope so,” I tell him, not sure whether he’s putting me on or not. Big Newton squats beside me and ties a red silk scarf around my right arm.

“Uh, what does that mean?” I ask.

“That means you’re one of us,” Newton grins.

When everyone’s had just enough to drink to be in a jovial mood, it’s tempting to see Wayne, Newton, Two Feathers, American Horse, and the other T&J regulars as Indian versions of Steinbeck’s carefree Mexican primitives, The Corner as an Indian Tortilla Flat, a refuge from sullied civilization. But to look more closely at the dark mask of Wayne Hunter’s face, a mask that scarcely hides the bitterness, is to see the truth. And to see the puffy, youthful features and vacant eyes of Daniel American Horse, a man caught between two cultures with no place to go, is also to see the truth.

Juanita Elder, director of the American Indian Center, sees it every day and tries to do something about it. I tell her about Bud Two Feathers, and she can’t explain what might have happened. “We have resources where we can get housing, we can get food, we can get clothing. We have a food stamp office here two days a week, and lots of times the staff takes money out of their pocket and gives it to people who don’t have, say, bus fare or enough money to buy milk for the baby. We have the resources to get anything we need, so he should have been helped.”

My impression of the American Indian Center is that it is helping a lot of people, and probably more effectively than the BIA and other government agencies are able to do. The American Indian Center operates a pre-school, a youth program, and a halfway house and group therapy program for alcoholics. Its Oak Cliff counterpart, the Inter-Tribal Center, operates a clinic, a sales outlet for Indian arts and crafts, and it works closely with a Manpower employment program.

Juanita Elder, an attractive mother of five who taught in the Dallas public schools for 19 years before coming to work at the Center three years ago, suspects the widespread Indian alcoholism may be due in many cases to the depression and frustration of coming from a rural area and trying to find a place in the city. “When an Indian comes from a rural area or from a reservation, he often discovers he doesn’t have a saleable skill, and often his family doesn’t have the food that it needs or the clothing. When he’s not able to provide for his family he becomes depressed and frustrated. He turns to alcohol, and that in turn causes lots of other problems.”

But while for some Indians East Dallas is a mere resting place in a lifetime’s wandering, the urban Indian no longer has to face a choice between alcoholism or assimilation. As groups like the American Indian Center and the Inter-Tribal Center continue to work with those Indians who choose to stay in the “cold-blooded city,” a visible urban community is developing, a home on the cement prairie.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author