Editor’s Note: This article reflects the state of Dallas leadership today, as described by 15 of the city’s top civic leaders, most of whom are pictured on the following pages. These leaders granted D’s editors lengthy interviews during the summer of 1974, and gave candid, off-the-record assessments of their peers, their city and its institutions. In 1961, Carol Estes Thometz interviewed many of the same men, resulting in the remarkable book, The Decision-Makers. Ms. Thometz found seven men at the top of Dallas’ power pyramid. Since then, two have died, and three have faded from the top. Today, just 13 years later, only two remain. They have been joined by seven other men pictured in this story. Six young men have been identified as “comers” on the Dallas leadership scene. Their future, and the future of Dallas civic power, has been examined by the editors in the following narrative. The editors extend special thanks to Dallas historian A. C. Greene for his thoughtful and perceptive contributions to this article.

Last April, a young, on-the-rise businessman was in the office suite of a prominent member of the “Dallas establishment” talking business. As the meeting drew to.a close, the conversation turned to city politics. Suddenly, the older man dismissed the small talk with an abrupt wave of his hand.

“I’ll tell you what’s wrong with this town. No leadership anymore, that’s what. Want to know who runs this town? Nobody, that’s who,” the older man said, raising his voice.

“They won’t listen to us anymore. So who are they listening to? Who knows? Nobody. Anybody. In the meanwhile, the whole town is going to hell in a hand basket.”

The young man was bewildered. It’s not an uncommon feeling in Dallas these days. At downtown business meetings, at North Dallas cocktail parties, at political strategy sessions, the same questions are being raised over and over again. What’s happened to the celebrated Dallas oligarchy? Who’s running this town?

Answers don’t come cheap. It is, to understate, a confusing state of affairs. And most attempts to clear the air recently have only compounded the confusion. The Dallas Times Herald, in what turned out to be a parody of the confusion, last May consumed two full inside news pages with a look at “the changing power structure.” The story concluded there was, indeed, no leadership crisis to worry about and that, in fact, Dallas was entering an era when “the city has a wealth of leadership rather than an annointed leadership of wealth.” The paper proceeded to support that contention by listing 110 men and women (including – now get this – Roger Staubach) as “Dallas leaders.”

Well, heck. We’ll grant that there are at least 110 influential people in the city. Dallas has always had a reservoir of talented and capable people in places of influence. But that’s not quite what the word “leadership” has meant in the past. Just what it means today – as the Herald’s telephone book approach to the situation suggests – is not a simple matter.

Starting with first things first: We know the same people – the oligarchy, the establishment, whatever – who ran Dallas five, even ten years ago, still basically hold the reins today. The John Stemmons, the Jim Astons, the Bob Cullums, the Erik Jonssons, et al, still, as one observer noted, “got the big clout.”

But we also know that power, once virtually absolute, is eroding, slipping, fracturing. The Old Guard is losing its grip – from age (just shy of 60 on the average), from apathy, from hardheadedness, in some cases, from death. Its power is diminishing in scope, in depth, in intensity. The oligarchy is still the game in town, but it’s no longer the only game.

There is the matter of Wesley Arthur Wise, the sportscaster who had the gall in 1971 to run against the establishment’s “annointed one,” Avery Mays – and win. Not just win, but win big. Where did he come from? He didn’t fit the mold. He wasn’t wealthy, wasn’t a corporate head, wasn’t a member of any major civic organization. He wasn’t even a businessman.

What the establishment could not understand – still, perhaps, does not understand-is that the “mold,” as such, doesn’t wash white across the board anymore. Wise could get votes. He got more votes than Avery Mays. He may still be able to get more votes than anyone the establishment throws up against him next spring-“mold” or no “mold.”

Wise’s performance at City Hall has been lackluster at best (See page 54.). But who wants to stand up there and get creamed by a TV personality? Not Jim Aston for one. When the Big Boys gathered at the Big Table in the Big Room at Republic Bank last summer to try to strong-arm Aston into running for mayor against Wise next year, Aston read the handwriting on the wall very clearly: Thanks, but no thanks, guys. Things simply aren’t the same. And they never will be again.

The 1972 Trinity River canalization bond election is perhaps a better case in point. Canalization of the Trinity was the establishment’s last great dream, its parting monument to “bigger is better.” The powers-that-be had no reason to suspect the citizenry at large would feel any differently than they did about running a barge canal through the middle of town. “The voters always took our advice before,” one establishment member commented, with classic understatement. Leaders had worked for canalization of the river for decades. It was good for Dallas business, by golly, so it was good for Dallas. The oligarchy thought so. The Dallas Morning News knew so.

The voters didn’t. The Trinity canal bond program was defeated by a landslide. Like befuddled parents with rebellious teen-age children, the oligarchs could only wag their heads in dismay. “Where did we go wrong? Where did we go wrong?”

Government by Proxy

It wasn’t always this way. There was a time, not too long ago as a matter of fact, that the establishment could expect the voters to rubber stamp any bond program, civic project or candidate it deemed “good for Dallas.”

In 1964, a vacancy in the mayoral chair was to be filled in mid-term, which, according to the city charter, requires a vote by the city council. One morning Erik Jonsson was simply announced in the newspaper as the new mayor. Some of the city council members, who were supposed to have made the decision, claimed they hadn’t even been told.

It’s called the politics of paternalism, government by proxy. A group of big businessmen – wealthy, prominent, philanthropic – passing absolute yes-or-no judgment on any civic matter involving a few thousand dollars or a handful of people. Not very democratic, but it works. The politics of paternalism, for all its shortcomings, has built a prosperous city, a government free of corruption, a community insulated from some of the monstrous urban problems facing other American metropolises.

Rule by oligarchy was born under R. L. “Uncle Bob” Thornton St., the nimble-minded, self-made banker who in the 1930’s proposed to the two major bankers at the time, Nathan Adams of First National and Fred Florence of Republic, a civic ruling class of presidents and board chairmen of the largest Dallas businesses, men who could say yes or no and have it mean something. As Thornton explained in his trademark grammar: “We didn’t have time for no proxy people – what we needed was men who could give you boss talk.”

Give him boss talk they did. Thornton, a sort of country genius, performed a miracle in 1935 when he decided to persuade Texas to designate Dallas as the site of its greatest celebration, The Texas Centennial Exposition. Dallas didn’t have the Alamo, or the San Jacinto battlefield, or the state capital; it wasn’t even in existence when Texas won her independence. Texas’ other major cities were understandably surprised at the impudence of this upstart town in North Texas. But with Thornton rolling the dice and a stake raised by other leaders, Dallas took the legislature by storm and won the gamble. It put up a hefty $10 million (remember, this was the Depression) and came out with 13 million visitors from all over the world, millions of their dollars and international publicity which formed the legend of “Big D.”

The success of the Texas Centennial venture prompted Thornton to formalize the leadership structure for future contingencies. In 1937, the Dallas Citizens Council was chartered to “study and confer and act upon . . . any matter which may be deemed to affect the welfare of the city of Dallas.”

It was a civic machine to behold. Through its network of detached, but controlled units (Citizens Charter Association, Committee for Good Schools, United Way), it elected over 90 per cent of the city council, named all but two mayors (and one of those was a club member who jumped ship), firmly controlled the school board, yea-or-nayed all civic fund drives, and advised-and-consented every remotely important municipal decision. Through the newspapers (both publishers were members), it was able to write its own news, promote its special causes and dismiss critics and criticism at the local level.

It was a time of economic emergency; survival, not style, was the key to success. There wasn’t time for dilly-dallying. The need for quick decisions forced effective control of the city into the hands of the three bankers and half-dozen other decision-makers. When a sizable financial commitment was required, an added twenty or so members joined in to consider the options.

The “dydamic men of Dallas” were in full swing. There were roads to be paved, skyscrapers to be built, new businesses to be wooed and won, an entire city to be fashioned and constructed on the uninviting plains of North Texas. The businessmen-turned-city builders weren’t about to be denied.

In 1931, when the political hacks who had controlled city government refused an ultimatum to “get clean or get out,” the CCA responded with a shock attack reminiscent of a Raid commercial. These new city fathers were rough, uncompromising, undemocratic, and those were the very attributes that enabled them to create a city where none should have existed, or could have existed without them.

The Clout Quotient

There was a definite formula to becoming a player on “the team.” Power had ground rules. You didn’t use it to compete or undercut. You cooperated, always, for the “good of Dallas.” (If it happened to help your business, as it often did, fine. But don’t get greedy.) Personal wealth was assumed, but the giving of your time and talent to civic projects was at least as important as giving your money. (There are a number of wealthy men in town today who have little civic clout because they don’t donate enough time to the right projects. (See page 54.) As one longtime member of the team put it: “You’ve got to go through the chairs – United Way, Chamber of Commerce, something in the arts maybe – before anyone’s going to pay any attention to you.”

It was also imperative that you head a large business which can provide plenty of warm bodies for fund drives and projects. More important, chief executives can be counted on to assign their money and manpower and have it mean something.

That brings up a key point too often forgotten. The establishment has always been made up of men, but they represent powerful institutions. The trunk of the power tree was, and is, the big downtown banks, Republic and First National. The chief executives of the big banks sit at the Big Table regardless. So do the newspaper publishers, the heads of the major utilities (DP&L, Lone Star and to a lesser extent, Southwestern Bell) and the bosses of the major insurance companies and retail stores. Of course, some leaders, such as Bob Cullum is, or Stanley Marcus was, rose principally by sheer force of personality, but the fact that they headed substantial institutions didn’t hurt. (It’s ironic that Thornton’s Mercantile Bank didn’t inherit his mantle.)

In consensus, this cult of corporate clout was virtually unstoppable in anything it wanted to accomplish. That was the point. As one establishment potentate remarked: “You get the banks, the utilities, then insurance, the big stores and the papers. Once you got them, you don’t need anyone else.”

The major reason these independently powerful (and often competitive) business institutions worked so efficiently together is that each had a big stake in Dallas as a whole. What happened to the city directly affected profits. If Dallas became unattractive to outside corporations or to people looking for a new home, it was the banks, the utilities, the insurance companies, the big stores which paid most dearly. (Independent oil companies are a classic example of the opposite. They could just as easily be located in Wax-ahachie and do as well.)

Something called “float” enhances the natural rapport among these institutions. Simply, float is the amount of cash that stays in an account long enough to be used interest free by a bank to make loans, investments, etc., and generally to operate well above its capitalization. So the banks (don’t forget, they’re the center of the power structure) like float. And guess who can provide it, lots of it.

That’s right. It’s the utilities (DP&L’s float runs into the millions on a day-to-day basis, and Lone Star and Bell are not far behind), the insurance companies, the big retail outfits. Even the papers provide decent daily floats, though their “must” status in the power structure has more to do with the fact that no power structure (not even the Dallas oligarchy) can do without friends in the media.

So it’s no surprise that behind the great majority of Dallas’ leaders you’ll discover a common denominator- big float. Remember, the Dallas Citizens Council was founded by bankers and remains very much a bankers’ club. Bankers, when sizing someone up, rarely look at IQ – they look at float.

And while float cannot be counted as the entree to the power structure, it’s a darned good start. Let’s put it this way: If you have big float, and you’re willing to run through the chairs, and along the way you don’t do anything freaky, you’re in.

Future Shock

The Dallas oligarchy was formed by businessmen to run Dallas as a business. However, the time comes, as any businessman knows, when a successful enterprise outgrows its original management structure. The rules of the game change and so do the long-range goals.

This is more or less the position Dallas finds itself in 1974. The city’s smack dab in the middle of a growing pain, a transition from town to metropolis, with one foot still entrenched in the past and the other groping aimlessly forward. It’s a helluva fix.

The result, for the present at least, is a future shock of sorts. The city has outgrown its traditional perceptions of itself. And, with that, it has outgrown its traditional leadership.

Sure, the Old Guard and the Old Ways still basically predominate – but only by default. The establishment lingers in power because no one is around to pick up the reins. No order of succession, no built-in system assures that the mantle of leadership is passed on.

All traditional channels for this have slipped, slid or never gotten off the ground. The Dallas Assembly, formed in 1962 by Thornton as a leadership school for the power structure, has virtually fizzled, even among its members. As one member, who met with the Assembly in Aspen, Colorado, last spring put it: “The Assembly had to go to Aspen … we don’t even recognize each other in Dallas.”

The “new CCA”, fashioned in 1973 by John Schoellkopf, has succeeded in bringing some new faces to the leadership scene, but has not yet shown the vision or strength the city needs.

Too, the most often mentioned of the young “comers” are, for one reason or another, not likely to take the helm with as strong a grip as the Big Boys of old. (See page 50.)

So it’s not clear who the new faces in Dallas power will be. It is reasonably clear, however, that the rules and the formulas and the survival tactics will be different.

For one thing, the banks are changing and that means the bankers are changing. Within the past four years, the unimaginable has happened: The big banks are no longer Dallas banks. They’re Texas bank holding companies. Republic and First National are now among the top 20 on the Federal Reserve’s non-New York City bank ranking, and that means they now operate well beyond the city limits of Dallas.

Each owns banks in cities across the state; their heretofore undivided attention to the “good of Dallas” suddenly is divided. They are understandably as concerned with the growth of the smaller Texas towns where they own banks as they are with the growth of Dallas. The risks of local Dallas politics, then, begin to outweigh the benefits.

As the banks have moved out of Dallas, people have been moving in. Lots of people. And they’re not coming solely from Kilgore and Commerce like they did in the old days. They’re now coming from all over, principally from up East. The guy who pulls up next to you at the stop light on Turtle Creek probably doesn’t know or care who Jim Aston or the Dallas oligarchy is, and probably would be flat insulted that a bunch of downtown businessmen are meeting in secret to select his city’s mayor.

We have something new on our hands. Special interests, power factions- ethnic, political, ideological, and geographical – are fragmenting the city. Dallas is no longer the neat, homogeneous WASP, middle-class package of the Thornton days. The city is 25 per cent black, has a growing blue collar class, burgeoning suburbs, and lots of newcomers.

People don’t even talk about Dallas as simply “Dallas” anymore. It’s the “City of Dallas,” the “City of Richardson,” the “City of Piano,” the “City of Garland” and so on. (The newspapers and TV stations use the term “metroplex” with irritating frequency.)

We are beginning to feel the fallout of this social fission. Single member districts are opening avenues for the politically ambitious who previously were barred from receiving establishment blessing. Too, folks just aren’t scared to stand up to the Big Boys anymore. Clint Murchison may be persona non grata to the downtown crowd, but he didn’t hesitate to take his team and his stadium to Irving when he was pushed too hard. Neither does Southwest Airlines’ Lamar Muse appear worried that he’s defiling a major establishment sacred cow, D/FW Airport, in sticking to his guns on the Love Field flap.

This kind of behavior by average citizens used to be plain unpatriotic. Only Republicans and a few unreconstructed liberals ever had the gumption to thumb their noses at the establishment in the past. But then (sniff), they were misfits to begin with.

Something else is playing a role in all of this. Business, as such, is not at all what it used to be. It’s tough these days to find a bona fide yes-and-no man of the Thornton ilk. Fewer and fewer businesses in Dallas, especially the bigger ones, are family-owned or even totally Dallas-owned. Yesterday’s small, privately held enterprise is today’s huge corporation, with attendant problems of the SEC, FTC, unions, conglomerates, subsidiaries and stockholders. That means that yesterday’s yes-and-no man is today’s hired hand, usually with a parent corporation watching carefully off-stage. Alan Gilman may be interested in running for mayor, but you can bet he’ll check with Sanger’s parent, Federated, before he makes a move.

Scenarios for 1984

It’s understandable that observers of this state of affairs have different notions about where it’s leading us. The current talk around town posts five possible scenarios for the future:

Anarchy Theory. “Oligarchy . . . to anarchy,” muses one Old Guard leader. His suggestion, that we may have encountered a problem which has no solution, finds little support from more optimistic businessmen. He argues in reply, “Look, we’ve had no mayor for three years, we lost our symphony, the State Fair is fading. The city continues to boom in spite of it all. There won’t be a need for old-styled leadership until Dallas hits hard times.”

Vacuum Theory. A well-known Dallas historian disagrees with the anarchy idea. “Power, like nature, abhors a vacuum.” In the future, he suggests, Dallas will be run by politicians, not patrons. That means partisan politics at city hall, with the predictable deals, bargains, dirty campaigns, good men hurt, good causes ignored. Accordingly, the mayor’s job will change from an amateur’s avocation to a professional position. The luxury of a $50-a-week mayor will become too expensive, even if that salary once was sufficient to attract the talents of an Erik Jonsson. And a professional mayor needs a power base, not comprised of businessmen, but of other politicians, who will in turn look to the mayor for their political lives and futures.

White Knight Theory. Two younger men, one a Republican politico and the other a rising corporate executive, believe the establishment will survive. “Anyone who thinks those guys are developing rigor mortis ought to try to fight them,” one remarks, adding that he has. “All they need is one young rally-round-the-flag leader,” the other says, “who has access to their money and clout. He’s not Charlie Terrell or John Schoellkopf, or anybody else I can think of, but if he’s out there and if he starts to move fairly soon, he could restore everything that Bob Thornton built.” The White Knight, theory, while interesting, has one major drawback: he’s not out there.

New Establishment Theory #1. A more romantic assumption, offered by one of Dallas’ leading liberals, is that a new power structure of divergent interest groups may arise to challenge the business interests. How groups with differing needs and aspirations will form a cohesive power bloc and sustain it against any prolonged attack, he leaves to the imagination.

New Establishment Theory #2.

A Dallas attorney suggests a notion which may prove to be just as illusory. “There are plenty of talented young businessmen in town who have money, time and a concern for this city. They don’t fit the traditional formula, which is good since the traditional formula no longer fits the town. They know each other and trust each other, and they’re reasonable. If placed in the proper conditions and stimulated by their own friends, they could establish an informal, but powerful, leadership group.” The reason such a new establishment would be successful, he argues, is that it knows the city, knows its own generation better than the oligarchy does. “The Old Guard has failed because it has been incapable of achieving the most necessary of all modern political weapons – subtlety.” To give him his due, our attorney has a point. A city dominated by business, as all cities are, requires that businessmen be a vital component of any new power equation.

Bob Thornton used to say that any fool can predict the future. It’s making the prediction come true, he would add, “that wears you a little thin.”

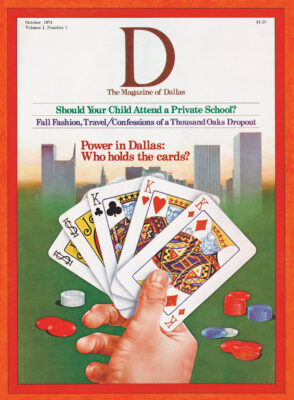

It’s easy enough to determine who holds the cards of Dallas power today. But we cannot know what the cards hold for Dallas until the hand is played, and that may take a few years. Until then, all bets are off.

Last of the Yes-and-No Men

John Stemmons

Hard-working, rich, tough, the last of the old bulls. He’s still number one. With brother Storey, turned family-owned land into Stemmons Freeway industrial park and office complex goldmine. Has a short fuse and occasionally offends contemporaries. A fairly generous political giver and can raise plenty more. Serves on boards of Republic, DP&L, Dr Pepper, Southland Financial Corp., and is a director of $40-$50 million Hoblitzelle Foundation, which doles out almost $2 million locally each year. Stemmons has more political moxie than his fellow oligarchs – he’s well-connected at the County Courthouse and has a hand in the pie at City Hall. (Councilman Russell Smith is said to be Stemmons’ current man on the council.) At 65, Stemmons, a late peaker in the power picture, is still going strong. He probably will not fade as fast as his peers.

Robert Cullum

The Henry Kissinger of Dallas politics. His popularity makes him the go-between with Republic and First International camps. He and brother Charles head Tom Thumb food empire ($73.7 million in assets). With Stemmons, makes a devastating one-two fund raising punch. A fairly large CCA benefactor over the years. (Councilman George Allen is said to be his most receptive “friend” on the council.) Board member at Republic, Dallas Federal Savings, Dr Pepper, Fidelity Union Life and Hoblitzelle. Age (62) and arthritis are slowing him and insiders say he’s beginning to fade, save his ongoing presidency of the prestigious State Fair of Texas.

James Aston

Just a shade back of Stem-mons and Cullum. Makes it through sheer corporate and foundation might. At 62, heads one of the state’s biggest bank holding companies, Republic of Texas, and is president and director of the powerful Hoblitzelle Foundation. Has the model Tex-ana background. A self-made man who came off the farm, won All-America honors as A&M quarterback, became Dallas city manager, then moved directly into banking. A real team player. Serves on boards of Zale Corp., and Times-Mirror, parent company of The Dallas Times Herald. Turned down establishment draft for mayor this past summer, possibly because of increased business pressures, civic exhaustion, or both. An enormously humble man-some feel to a fault.

Semi-Heavies

Lee Turner

As DP&L president, Turner holds sway over major bank “float” in town and plenty of manpower. Utility is the city’s largest taxpayer. At 47, Turner’s barely in, but his position and the leadership legacy of predecessor C. A. Tatum guarantee him future clout.

Jim Chambers

Times Herald publisher is an automatic, although the paper’s West Coast ownership has hurt it with powers-that-be. Some of its non-establishment political endorsements of late have raised establishment eyebrows. At 61, Chambers is regarded as more “sensitive and receptive” to new ideas than his counterpart at The News, Joe Dealey.

Avery Mays

1971 mayoral fiasco seems to have canonized him among oligarchy members. He’s not noted for his ingenuity, but at 63 is a hard worker at the nitty-gritty level of civic projects. A major contributor and a proven money-raiser.

Joe Dealey

The News has the pedigree, the affluent North Dallas readership and the benefit of home-ownership. All of which means Dealey is guaranteed a prominent position in the inner circle. The News’ editorial influence is still counted as tops in town. Dealey is 55.

Robert Stewart

Heads $4 billion bank holding company, First International – and, baby, that’s clout. Ruffled some feathers in ’71 by nixing CCA’s top mayoral choice, Charles Cullum. Has apparently rejoined the fold this year, promising to support an establishment candidate against Wes Wise next spring. Money, banking interests said to outweigh civic do-gooding, which keeps him out of the top echelon. At 48, though, he’s young enough to make a move if he wants.

Erik Jonsson

At 72, Jonsson has abdicated his leadership as a doer (the airport was his last great pet project) , but his vision makes him a respected advisor, with plenty of veto power. A big giver at all political levels.

Al Davies

Old guard leader of the big merchants. Heads regional Sears operation headquartered in Dallas. At 62, he maneuvers sizeable corporate contributions and commands a hefty army of civic troops. Another “good ol’ boy” type, Davies is always on call for yeoman’s labor in the civic trenches.

Bill Seay

Chief exec at Southwestern Life Insurance is strongest civic leader from the insurance community. Only recently arrived, but at 54 he’s moving up rapidly. Has touched the right bases – Citizens Council VP this year, Chamber of Commerce, United Way.

Lloyd Bowles

As chairman of Dallas Federal Savings & Loan, the state’s largest S&L ($687 million plus), he has to have a place at the Big Table. While seldom publicly recognized as a leader, his counsel is respected. He’s 58.

Comers

George Schrader

This city manager is more than just a manager. He’s the man to see at City Hall. Insiders say Schrader has gained power through sheer intelligence, hard work and Mayor Wise’s low profile in the day-to-day matters of city government. At 43, he has “superbureaucrat” status City Atty. Alex Bickley once held.

W. C. McCord

Hard-driving individualist who heads Lone Star Gas. At 46, heads an institution with plenty of “float” and taxpaying clout. Is said to be unafraid to speak his mind, often causing sparks to fly within the inner circle. Building respect and could come on very fast.

Alan Gilman

One of the busiest civic bees around. He’s young (44), head of a major institution (chairman of Sanger-Harris), involved in the “right” civic projects. Gil-man is said to be interested in city politics, though attitude of Sanger’s parent, Federated, may be a factor.

John Schoellkopf

Architect of the “new” CCA and the youngest comer of all at 34. Consensus is he has it all: time, money, entree, but may lack the motivation or the strength. Because of his name, he holds favorite nephew status with Big Boys. (John Stemmons loathed Schoellkopf’s liberalized CCA, but still has few disparaging things to say about “Johnny.”)

Walt Humann

Vice-president of LTV at 37. One of brightest and smoothest guys around. Somewhat politically naive, but has plenty of time to learn. Makes everybody’s “nice guy” list and has a staggering resume. Big liability is that he isn’t a chief executive.

Overrated Power

Power in Dallas has always been defined by an oddball formula: You have to be rich and head of a big business institution, but that’s not all of it. You also have to do your civic part – “run through the chairs,” as John Stemmons says.

United Way, Chamber of Commerce, Dallas Citizens Council stewardships are musts. It helps to do something in the arts; hospital drives, especially if you head them, are very good for points. Giving of your time civically and politically within the inner circle is more important than giving money.

How much press you get still has very little to do with real clout. The Big Boys don’t count newspaper clippings when assessing potential new family members.

There are some rich, prominent folks in town and a few “press saints” who have the appearance of power, but who don’t really cut it because they haven’t followed the formula. Here are the most commonly overrated:

Trammell Crow

An enormous giver of political money, but stingy with his time. And that makes all the difference in the world. His game is global, his tent just happens to be here. Also, his float is not as great as one might think. He has what one businessman dubbed “a diluted base.” His money is spread as far and wide as his land holdings.

Ross Perot

Time counted him as an emerging power in the Southwest, and he could be – but only in the business community. In terms of civic influence in Dallas, Perot is nowhere. He’s a loner, for one thing. The Wall Street brokerage bomb and the POW razzle-dazzle haven’t helped. Teeth grind downtown at the mention of his name. He’s another one who’s given plenty of money to the wrong causes and little time to the right ones.

H. L. Hunt

Eccentric politics and lack of the “right” civic involvement make Hunt virtually cloutless in Dallas, no matter how rich he is.

The Murchisons

John is popular, but not particularly respected. Clint Jr. is an outcast because he took the Cowboys from the sacrosanct Cotton Bowl to Irving (of all places). That’s heresy. Also, he didn’t donate his Trinity green belt land to the city as John Stemmons did. Again, lots of money, but no power.

Wes Wise

He’s overrated only because people assume anyone with the title “mayor” must have clout. Not so. Wise is strong at the ballot box, but that’s it. Downtowners tend to ignore him when making big civic decisions. About all he has going for him is good press and an “independent” image. But even that’s beginning to wane since his business fell apart and he has had to take a job with Trammell Crow.

Garry Weber

A “press saint,” if there ever was one. A genius at getting his name in the paper. Real civic clout, however, is hardly perceptible. Showed some moxie at the polls last time out by whipping CCA’s Fred Zeder, but many insiders feel it was more Zeder’s loss than Weber’s victory.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.