Steven Becker used to be a pirate. A pirate of the financial world, that is. He ran his own hedge fund. He was an activist investor, firing broadsides at underperforming firms, jumping aboard their boards of directors, and shaking up their strategies. He spent his days mapping out strategies that involved alphas and betas and option-adjusted spreads and asset mixes and hurdle rates and risk arbitrage and all the other ins and outs required of activists of his ilk.

But since late 2015, Becker has been focused on different kinds of ins and outs. Literal kinds, like the ins and outs of customers at Horn Pond Plaza in Woburn, Mass., and Pacific Plaza in San Diego, Calif. In both those places—and some 750 others like them across the country—you’ll find a store operated by Tuesday Morning Corp., a 42-year-old, Dallas-based discount home goods retailer with 2,000 employees. Becker has found himself, quite unexpectedly, serving as CEO there since December 2015.

There are no pirates in Horn Pond Plaza, but there is a Tuesday Morning store just down from the Prana Power Yoga studio and Papa Gino’s Pizzeria. And in Pacific Plaza, there presumably are no captains of finance, but there is a Tuesday Morning that’s adjacent to Tweety Thai Cuisine and just around the corner from the Pretty Kitty Waxing Salon.

Is that good real estate? Can shoppers find the stores easily? Do those stores need to be revamped, as the company, which is in the midst of a turnaround effort, is doing to 20 stores a year? Or should they be relocated, as Tuesday Morning is doing to 50 stores a year? Or maybe just restocked with, say, more Peacock Alley flannel sheet sets that are being sold for just $29.99? Are those stores, and all the other Tuesday Morning stores, living up to the promise the company makes to all of its shoppers?

“Whether you are looking for upscale home decor, furniture, bedding, bath, kitchen, electrics, luggage, toys, crafts, pets, gifts or seasonal,” the company tells its customers on each store’s website, “you are sure to find your perfect treasure.”

That’s the kind of thing Steven Becker now spends his days worrying about, safeguarding treasure. Which, when you think about it, is quite a thing for a former pirate to do.

On June 5, 2012, Dallas-based Becker Drapkin Management, a hedge fund that Steve Becker had been operating with Matt Drapkin for a little more than two years, filed a form 13D with the Securities and Exchange Commission, showing it owned 5.7 percent of Tuesday Morning’s shares, a stake worth about $10 million.

A 13D filing often serves as the opening volley in a battle pitting pirates—er, activist investors—against companies in which they’ve invested. But Tuesday Morning didn’t put up much of a fight. Instead, the company granted Becker Drapkin’s request for two board seats. (One went to Becker, the other to Richard Willis, the CEO of a company Becker Drapkin had also invested in.) And Tuesday Morning also fired its longtime CEO, Kathleen Mason, at the hedge fund’s request.

(Mason would later sue the company for discrimination, claiming that her cancer diagnosis months earlier was the real reason for her dismissal. The company fought the claim, and Mason told the Wall Street Journal that the suit was settled “amicably” in April of 2014.)

Mason’s ousting was the most aggressive initial move Becker Drapkin had ever made. The fund’s strategy was not to pick protracted public fights with mega-companies, like famed investors such as Carl Icahn or Bill Ackman have done. Instead, Becker Drapkin Management sought out underperforming small-cap companies—firms with market capitalization below $1 billion, such as Ruby Tuesday and Converse—and tried to engage with management in an effort to improve their results. You could think of them as pleasant corporate pirates. “Change does not magically happen simply because an activist secures a board seat,” Matt Drapkin, who did not return calls seeking comment for this story, told research service 13D Monitor last year. “The true work of reshaping the company … requires working closely with the management team and board. Conflict at the outset of that process can mar future interactions. Unlike some, we do not go into a situation believing we have all the answers.”

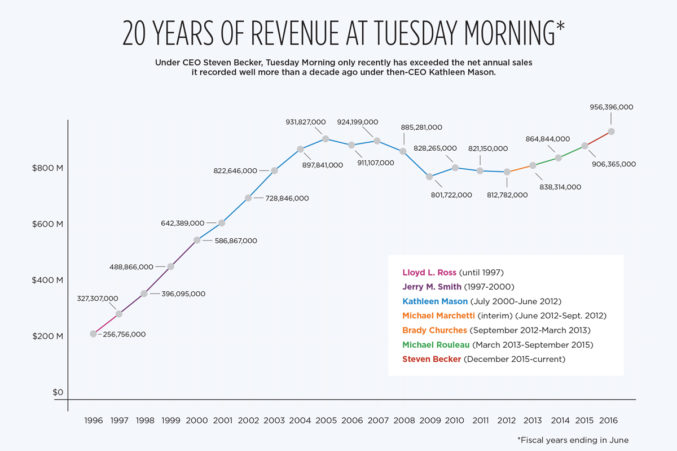

But even if Becker personally didn’t think he had the answers for Tuesday Morning, he did believe he understood its problems. “In June of 2012, Tuesday Morning was at the bottom of its category on every single metric,” Becker says from his office at the company’s headquarters off I-635 near Hillcrest Road. “When we got here, nobody on the board had experience in the businesses that Tuesday Morning was in, and the board had very limited retail experience overall. So we recruited for that.”

Within months, longtime board members David Green and Scarlett Johnson left, as did chairman Bruce Quinnell. Terry Burman, past CEO of Sterling Jewelers Inc., and Michael Rouleau, the former CEO of Dallas-based Michaels Stores and the founder of Office Warehouse, had joined, with Becker becoming chairman and leading the board’s CEO search committee.

Also within months a new CEO, Brady Churches, formerly of Big Lots, had been hired. Six months later, though, Churches was out—the company said he wasn’t the right cultural fit—and Rouleau, much to his surprise, was in.

Rouleau once knew 50-year-old Steven Becker, who usually goes by Steve, by another name: “Stevie.” That’s what Rouleau, and everyone else, called Becker when he was a teenager growing up near Boston. Back then, Rouleau was an executive with Lechmere, an electronics retailer, and Becker was friends with Rouleau’s son, Andrew.

Three decades later, with Rouleau retired and living in Arizona and with Becker needing board members who understood retailing, Becker reached out to Rouleau. “One of my kids told me that Stevie wanted to talk to me,” Rouleau recalls from his home near Scottsdale. “I was 74. I was retired. I didn’t need to work. But they convinced me to come visit, and once I saw the company, I felt an excitement of being involved with it. That did something to me that was incredible.”

That excitement motivated Rouleau to volunteer for the CEO post after Churches left. More volunteers followed. Seven former top Michaels executives called Rouleau after hearing of his CEO post and offered their services. “It was kind of like bringing the band back together,” Rouleau says. “This was a group of people that really knows how to turn a company around, because they’ve done it before.”

By 2014, after shedding some product lines and bolstering the supply chain, a new Tuesday Morning was dawning. The company’s improved operations helped it start riding a big wave that had carried deep discount sellers like HomeGoods to record performance in recent years. At Tuesday Morning, annual revenue was up to $865 million—a $50 million increase over 2012. The stock was up, too, rising from about $5 a share in 2012 to more than $21 a share.

That’s when Becker Drapkin hoisted its pirate flag and started selling some of its shares, reportedly pocketing $13 million in profit.

Early in 2015, Rouleau announced that a “rebuilding” phase aimed at long-term growth had begun, implying that the 18-month “turnaround” phase was over. The company’s stock promptly lost about 19 percent of its value the day after the announcement. And it kept sliding for most of the year, falling to $5.41 a share on Sept. 29—the day that the then-77-year-old Rouleau’s retirement was announced. Rouleau’s retirement came months ahead of when the company had expected him to leave, but his departure was accelerated after the company’s CFO, Jeffrey Boyer, another former Michaels executive, was recruited away to be CFO of Pier 1 Imports.

Becker says the board decided it would be easier to recruit a new CFO once a new CEO had been announced, which hastened Rouleau’s planned exit.

To fill the void left by Rouleau’s return toArizona, the company appointed an Office of the Executive Chairman to handle the CEO duties until a new chief executive could be found. The Office was a four-person oligarchy that included Becker; Phil Hixon (the company’s chief of stores, who once worked with Rouleau at Michaels); Burman, the former Sterling Jewelers CEO; and Melissa Phillips, a Home Depot executive who had joined the company as chief operating officer the year before.

Becker, at that time, had also stepped off the Becker Drapkin pirate ship. He sold his interest in the fund, leaving Drapkin to restart it in Darien, Conn., under a new name, and leaving Becker to focus on being a top executive at a public company for the first time ever.

Ten weeks later, after hiring an outside firm to conduct the executive search, Tuesday Morning hired its fourth CEO in four years. The company didn’t go with one of the candidates who came up in the search, but instead chose … Steven Becker. “We’d done a very thorough search and, frankly, we didn’t turn up candidates that we were excited about,” Becker says. “So the board asked me if I’d consider being CEO full time. When I joined the board in August 2012, I never in my wildest dreams conceived that I would become the CEO. But I felt an obligation to the people here. I was very enthusiastic about the opportunity. And I believed the senior management team here was very strong. I never even would have considered taking the job if I didn’t have this kind of senior management team to work with.”

In conference calls with analysts and in interviews with D CEO, Becker freely admitted that he has leaned heavily on other top officials at Tuesday Morning as he ramps up his executive skills. Among other things, he has a weekly meeting with board chairman Burman, a 30-year retail executive, to discuss strategy and review mistakes. “The level of organization and the range of skill sets that are required of a CEO is extraordinary,” Becker says. “I have adapted to it, but it was beyond my expectations.”

And yet, Becker says that he has found something familiar in the chief executive’s job. “What a retailer does is deploy capital and try to flow capital to the place where it is going to get the highest return,” he says. “So, effectively, we have a portfolio of investments [that] happen to be inventory. We’re managing that portfolio to achieve the highest return by turning it as rapidly as possible and achieving the highest gross margin possible and the highest gross margin dollar. The analysis required to know how to do that is very similar to investment analysis.”

That’s a deeply calculating way to talk about the business of selling Barbie dolls, coffee makers, and ceramic vases. But then that’s to be expected of Becker, those who know him say. “Steve is a super-smart guy,” says Ray Balestri, a partner at the Dallas law firm Bell Nunnally and an active investor who has known Becker since 1999. “He has well-honed instincts and the ability to perform deep and piercing analysis of complex facts with unknown variables.”

Still, Becker says one part of the CEO job he’s enjoying the most doesn’t involve crunching any numbers. “One of my favorite parts of this job is visiting people in Little Rock and Memphis and Oklahoma City and spending time with them and understanding their challenges,” he says. “Until you have this kind of executive role, you don’t truly realize how important it is that every interaction you have be inspiring. You are setting an example at all times. You are leading people, working as a team, and encouraging everybody to be their best.”

Becker is not the first activist investor to take a CEO role with a company in which he invested. Eddie Lampert, who runs ESL Investments, kicked off that trend in 2013 when he became CEO of Illinois-based Sears Holdings, a retailer that has struggled ever since a 2005 merger with Kmart that Lampert pushed as chairman of the Sears board. Last year, Lampert’s fund loaned the company $300 million to keep it afloat.

Tuesday Morning’s debt is much more manageable, and has nothing to do with its activist investor-turned-CEO. The company has $32 million in debt against $950 million in annual revenue—a healthy ratio by most accounts. And although profits fell from $10.3 million in fiscal 2015 to $3.7 million in fiscal 2016, due to problems with a new distribution center in Phoenix, the company is still in the black for the moment.

The company’s stock, however, was off 76 percent from January 2015 to November of 2016 and continues to hover near $5 a share—just about where it was when Becker Drapkin Management first bought into Tuesday Morning. And most of the five stock analysts who officially follow Tuesday Morning rate its shares a “hold.”

Still, Becker thinks Wall Street will eventually cheer the improvements the company has under way. “We’re only in the second or third inning of a long ballgame,” he says. “This is a company that had been under-invested for many years. Now we’re working on building out capabilities like our supply chain and resetting our entire real estate structure. That’s definitely a multi-year opportunity.”

As those years go on, the company is looking to attract customers beyond its core demographic of women aged 50-74 who have household incomes of $100,000 per year. By building new stores and freshening up existing ones, Tuesday Morning hopes to draw younger customers to its daily deals as well. In fact, since Tuesday Morning abandoned its online commerce presence in 2013 under Rouleau, it is banking its entire future on new, improved stores. The company expects to continue closing 40 stores per year. It is relocating 50 stores per year from underperforming storefronts to brighter, cleaner locations nearby. It’s remodeling and expanding 20 locations each year. And it is opening 20 to 25 new stores in new locations annually. Taken together, this rebuilding will cost around $40 million a year.

As those years go on, the company is looking to attract customers beyond its core demographic of women aged 50-74 who have household incomes of $100,000 per year. By building new stores and freshening up existing ones, Tuesday Morning hopes to draw younger customers to its daily deals as well. In fact, since Tuesday Morning abandoned its online commerce presence in 2013 under Rouleau, it is banking its entire future on new, improved stores. The company expects to continue closing 40 stores per year. It is relocating 50 stores per year from underperforming storefronts to brighter, cleaner locations nearby. It’s remodeling and expanding 20 locations each year. And it is opening 20 to 25 new stores in new locations annually. Taken together, this rebuilding will cost around $40 million a year.

“We have a real estate transaction happening, on average, every three days for the nine months a year when we’re focused on real estate,” Becker says. “That’s an extreme challenge. But a lot of our customers were simply enduring the old Tuesday Morning experience. They used to find a store behind a shopping center where they’d probably have to go down a set of stairs or go into an alley. They’d do that because they knew they were getting tremendous value and finding tremendous merchandise. But the new stores are very well-located in prime shopping areas and they present a much better shopping experience. Now the merchandise really pops. And, as a result, our sales have picked up.”

If that growth continues, one Tuesday Morning analyst—Jeff Van Sinderen, with B. Riley in Los Angeles—says he believes Tuesday Morning, “could attract the interest of a suitor.” And, guess who would stand to benefit greatly from a takeover by a larger competitor? A competitor, for instance, like the company’s primary competition, TJX, the $30 billion retailer that owns TJ Maxx, Marshalls, and HomeGoods stores? Steve Becker, the former pirate.

Becker has been steadily putting his own money into Tuesday Morning stock since he was named CEO. He now has about 1.3 million shares in Tuesday Morning, or nearly 3 percent of the 45 million outstanding shares in the company. “I believe in the brand, the business opportunity, and the people at Tuesday Morning,” Becker says. “I have been a professional investor for over 20 years. I built my investment career making asymmetric investments—situations where my firm felt the market was not correctly measuring risk and reward. I do the same thing when investing my personal capital.”

And of course, if the company is someday sold, Becker does now stand to reap plenty of rewards. So it makes sense that he’s betting on his own, and his team’s own, success. After all, Becker, who makes $700,000 annually at Tuesday Morning, has a contract with the company that runs until June 30, 2019. “This was a company that was fading and that might have gone away a few years ago,” he says. “Now we’re building a big business here. We’re hiring. We’re contributing to the economy. That is not about me. It is a team effort here. I’m just one of the players.”