Some might call it a fitting end for people willing to place a wager on the death of another: to be cloistered in a crowded courtroom, watching helplessly as millions of dollars in legal fees are racked up, praying to recoup even a percentage of their macabre bets.

But that’s exactly the scenario that’s playing out for more than 20,000 investors embroiled in a battle to recover their investments from Waco-based Life Partners Holdings Inc. The situation is fraught with irony, as Life Partners and its investors engage in a bitter fight while former policyholders—who sold the fueding parties their policies and then wound up living longer than expected—seem to be having the last laugh.

Said to be the oldest “life-settlement” provider in the world, publicly traded, 24-year-old Life Partners is part of the secondary market for life insurance. Under its business model, the company bought life policies from sick or old people who no longer wanted or needed them, giving the sellers immediate cash payments. Life Partners then packaged these policies into fractional interests and sold off the interests to individual investors, who continued making policy payments until the original policyholder died. At that point the investor got the insurance payout, or death benefit—typically a 7 to 15 percent profit over time—and Life Partners got its cut as well.

Since its incorporation in 1991, Life Partners claimed to have completed more than 143,000 transactions for more than 29,000 high-net-worth individuals and institutions in connection with the purchase of more than 6,500 policies worth $3 billion. But, the company’s problems started when things didn’t go exactly according to plan. In reality, many people who sold their insurance policies did not die in the short period of time that Life Partners had touted or anticipated.

As a result, returns diminished for the company’s investors, who had to continue paying the premiums or risk losing their initial outlay once the policies lapsed. In most cases, investors allegedly weren’t told of the risks they were buying into. At the same time, Life Partners continued to demand “service fees” from investors—many of whom didn’t expect them—and, if they failed to pay the fees, Life Partners threatened to allow the policies to lapse.

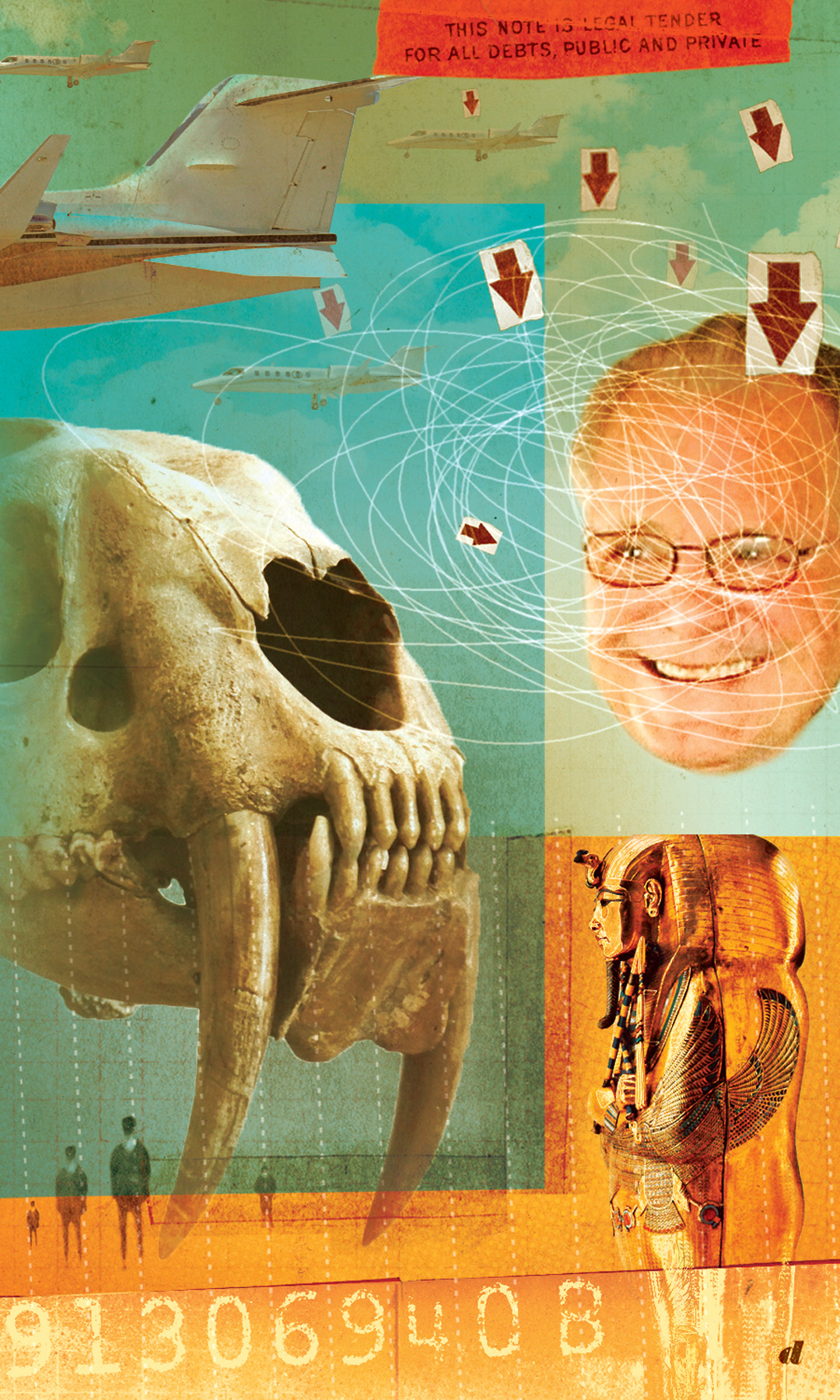

This went on for years, until the Securities & Exchange Commission put the hammer down in January 2012, seeking $2 billion in civil penalties against the company for an accounting scheme and allegedly misleading disclosures. In December 2014, the agency won a $46.9 million judgment against Life Partners and its two top executives. The total included $6.2 million against founder and CEO Brian D. Pardo (illustrated) and $2 million against R. Scott Peden, the company’s general counsel. The judgment effectively forced the company into Chapter 11 bankruptcy. But not before the Life Partners board of directors allegedly drained the company’s cash reserves through healthy dividends to stockholders.

Cash Cow?

All of this leads us to a downtown Fort Worth federal courthouse, which dozens of lawyers and hundreds of investors have been frequenting since January, as they fight for whatever can be pulled off the company’s bones. The convergence of troubled investors and high-powered lawyers has led to accusations that the lawyers working for the bankruptcy trustee have approached the Life Partners Chapter 11 proceedings as a cash cow.

“Thieves in suits—that’s what they are,” says Dallas resident John Delao, referring to the Thompson & Knight attorneys representing U.S. bankruptcy trustee H. Thomas Moran II. Delao purchased interests in 11 life insurance policies through Life Partners and, like many people interviewed for this article, acknowledged that he never would have done so had he known what he knows now.

In December 2014, the SEC won a $46.9 million judgment against Life Partners and its two top executives.

Even given all these shenanigans, Delao says, at least he received payouts from Life Partners once the policyholders passed away. As of early July, Moran was hesitating to pay any matured policies to investors until it became clear how such assets should be distributed. And in the meantime, some say, the legal meter is running at an alarming rate.

Now stuck in bankruptcy court, many Life Partners investors believe they’re being subjected to a “second fleecing” at the hands of Thompson & Knight, which accrued about $2.1 million in legal fees between March 13 and May 30. That works out to three lawyers billing more than $300 per hour, 24 hours a day, seven days a week during that period. Some investors wonder whether there will be any of their investments left before the attorneys are finished.

Thompson & Knight attorney David M. Bennett, the lead counsel for Moran, says his attorneys and Moran are doing all they can to untangle what he calls a wide-ranging fraud. The time spent on the investigation will be key in figuring out how to claw back what they can for the investors, Bennett adds. He says anger over the legal fees is misplaced. Instead, he says, the investors should be mad at Pardo and others who mishandled and committed fraud at Life Partners.

Bennett compared Moran’s job untangling the Life Partners hairball with the work now being done to reclaim investor dollars from Bernie Madoff and his “investment” company. Madoff is working off a 150-year prison sentence for staging the biggest Ponzi scheme in history. As of mid-August, the trustee charged in dissolving Madoff’s business has agreements to recover about $10.9 billion—half of the approximately $20 billion Madoff took—and he was still trying to claw back more.

“If you look at the Madoff case, they had real success,” Bennett says. “Will ours be similar? I hope so.”

Moran and Thompson & Knight are also attempting to preserve hundreds of life insurance policies with a face value of about $500 million, and with a potential payoff value of $2.4 billion. “If someone told us to quit working, that $500 million portfolio would collapse,” Moran says. “And we’re not going to do that.”

Another factor complicating Moran’s job is that some investors are having trouble paying their life-insurance premiums. At the same time, others who can afford to make the payments have fought Moran’s efforts to use the assets of solvent policies to cover premiums of troubled policies. In June, Fort Worth federal bankruptcy Judge Russell F. Nelms rejected Moran’s motion to do just that.

The core question bedeviling Nelms is whether Life Partners—or the investors—are the legal owners of the insurance policies. If the investors own the policies, the court has no authority to pull assets from one policy to cover another, he acknowledged.

For all of Moran’s court testimony about Pardo’s fraud, the Life Partners founder and former CEO is a fixture at the bankruptcy proceedings. Sometimes he even chimes in.

Those left holding insurance policies through Life Partners range from the likes of Delao—an experienced investor who has put money into life-settlement policies since 1995—to 52-year-old widow Glenda Pirie of Newark, Texas. Pirie had never ventured into the investment world until she took a chance with a faith-based investment counselor who promised her a sure profit. She sunk nearly all of her savings—$350,000—into 22 policies, and now can barely afford to pay her premiums to keep her 18 still-active policies from lapsing. Pirie lives in a trailer on $1,200 a month, via a check she receives from the Veteran’s Administration through the estate of her deceased husband.

Other North Texans invested their entire IRA savings in Life Partners insurance policies. They risk losing those funds—totaling an estimated $700 million—because laws ban putting retirement money into such investments.

At one point at the Fort Worth courthouse, a company stockholder marveled over the complexities of the case to Dennis L. Roossien Jr., a Munsch Hardt Kopf & Harr lawyer who’s representing unsecured creditors in the proceedings. “That’s the last thing you want to hear from your lawyer—that you’ve got an ‘interesting’ case,” Roossien told her in reply. “You want a case that’s simple and boring.” No doubt, this one is anything but.