While financial analysts and policymakers were drooling over the natural gas potential of the Barnett Shale field in North Texas in 2008, Pioneer Natural Resources Co., led by chairman and chief executive Scott Sheffield, was drilling its first horizontal well in South Texas’ Eagle Ford Shale field. Pioneer was looking beyond the gas, for the field’s oil and “rich” hydrocarbon liquids potential. Later, when the Bakken Shale in North Dakota became the hot shale oil play, Sheffield and his team were already analyzing the Permian Basin’s Spraberry/Wolfcamp shale in West Texas and beginning to recognize its massive potential.

Pioneer began focusing on the Permian in 2009, says Sheffield, a second-generation petroleum engineer. “We had a legacy 900,000 acres already, which we’d purchased from the ‘majors’ in the 1980s and ‘90s,” he says. “Historically we had been drilling 100 wells per year there, and using the extra cash to fund our international operations and deep-water opportunities. It took our geologists about two to three years to analyze the data of thousands of wells before we realized how big the prize was.”

Big, indeed. Irving-based Pioneer is one of the largest acreage holders in the Permian Basin, which is potentially the second-largest oil field in the world, behind only the Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia. The Ghawar is said to contain nearly 160 billion barrels of oil equivalent, while estimates by Pioneer and others place the Spraberry/Wolfcamp field, where traces of oil were first discovered on Abner Spraberry’s farm in 1943, at 50 billion to upwards of 100 billion barrels over time.

Pioneer’s Permian experience hasn’t occurred in isolation. While the trend has happened quietly, and some may not even realize it yet, America’s natural gas revolution has spurred a new oil boom as well. This energy revival is generating widespread economic and employment growth, and soon may help the U.S. become the world’s top oil producer, overtaking Saudi Arabia. The trend especially has benefited Texas, where oil production has more than doubled in less than three years, reversing a gradual, 28-year decline. Few firms have done more than Sheffield’s to lead, and capitalize, on this new American energy revolution.

What began in North Texas with the Barnett’s gas riches morphed into extracting oil using the identical, cutting-edge drilling technologies.

An engineering graduate of The University of Texas, Sheffield, 60, says his sights were never set on outsized growth. “I never expected to have 4,000 employees, or to be as big as we are today,” he says. “I focused on our company’s culture, the people, and at being successful. I then let it happen.”

So, how did it happen for Pioneer? And how did this new oil boom it helped shape come about?

•••

Part of the answer to the second question is: persistently low natural gas prices. Simply put, those prices made it less economic in recent years for producers to drill for and make money off gas. (Natural gas prices reached $13.28 million British thermal units in July 2008, but were continuing to hover under $4 as this issue went to press.) Another big reason for the new boom was the Barnett Shale, which led in turn to the rapid exploitation of other huge shale plays like the Marcellus, in Appalachia. The oversupply of gas, and the resultant low prices, caused E&P firms to look toward oil and “rich” hydrocarbon liquids to improve profitability.

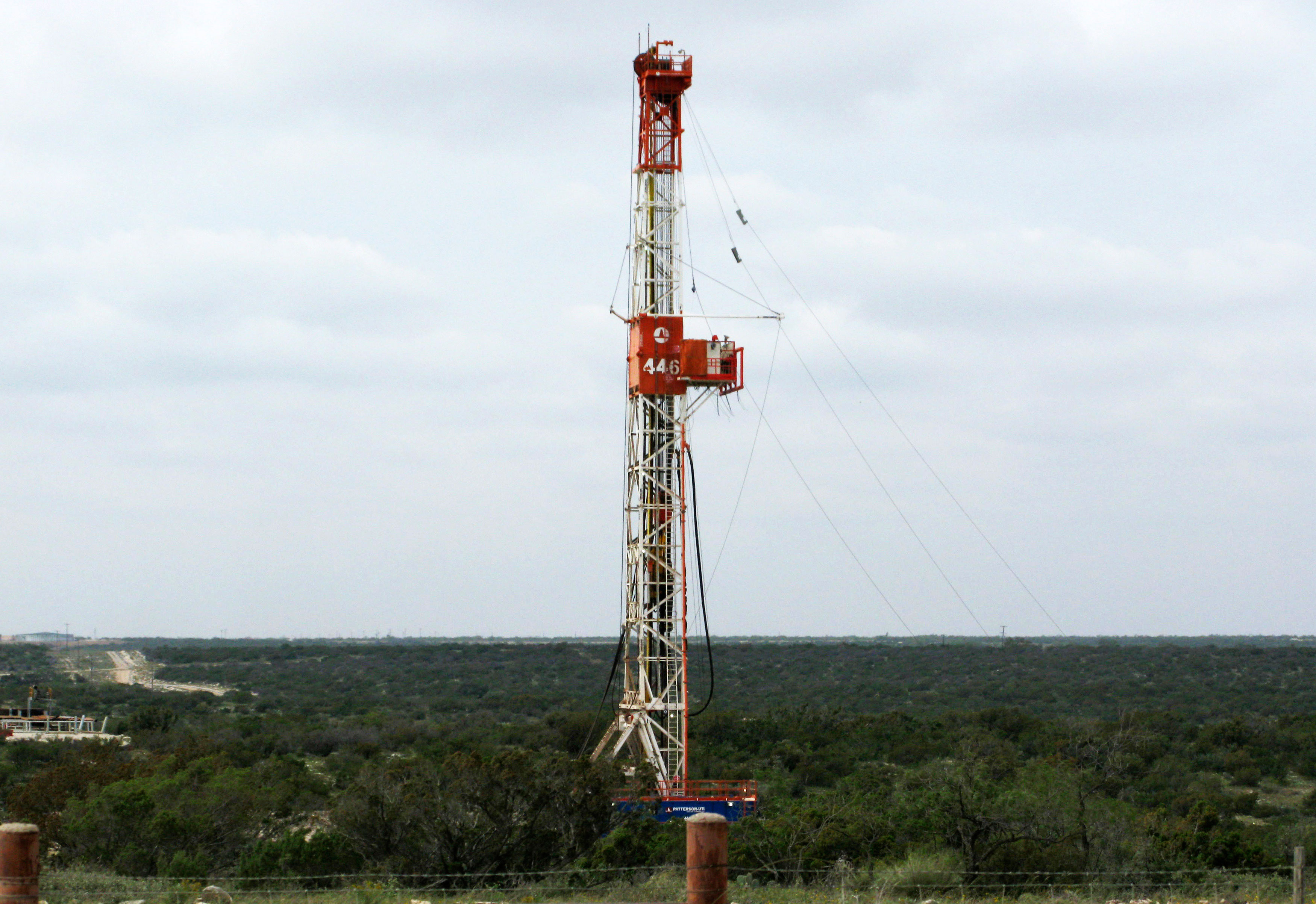

The Barnett was ground zero for the “unconventional” energy revolution (unconventional refers to energy extracted from the likes of tar sands and shale rock, plus wind and solar power). What began in North Texas with the Barnett’s gas riches morphed into extracting oil using the identical, cutting-edge drilling technologies—hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling—to free up energy from shale formations. Pioneer began ramping up its oil production with horizontal drilling in the so-called Edwards Trend, one of the most productive parts of the Eagle Ford Shale, in late 2008. The company now believes Eagle Ford is the second-largest U.S. oil field, behind the Permian’s Spraberry/Wolfcamp play, based on cumulative production plus estimated recoverable reserves. Says Barry Smitherman, chairman of the Texas Railroad Commission, of such developments: “What has happened in our state over the last five to six years is nothing short of a technological miracle.”

Ironically, the oil and gas majors, such as ExxonMobil, British Petroleum, and Shell, were not leaders in this unconventional energy “miracle,” though they have participated since. The “indies,” on the other hand, have been richly rewarded for their foresight in this arena. Since 2009, for example, Pioneer has been the top-performing energy stock in the S&P 500 oil and gas index, even ranking No. 6 in the overall S&P during this period.

Sheffield, who spent his high school days in Tehran, Iran, because his father, a petroleum engineer, was stationed there, credits living overseas with helping him understand other cultures, which is increasingly important in the energy field. “Pioneer used to be 40 percent global, but now Chinese and Indian firms are investing in the U.S.,” he says. In fact, government-supported national oil companies around the globe are forming more joint ventures with independent U.S. firms like Pioneer to explore unconventional resources here. For example, Pioneer recently formed a joint venture with China’s Sinochem Petroleum USA LLC, a Sinochem subsidiary based in the U.S. The JV is a $1.7 billion deal, with Sinochem snagging a 40 percent interest in a highly promising part of the Spraberry/Wolfcamp play.

The U.S. energy revival, analysts say, is due largely to the nimbleness of independents like Pioneer. “Even at UT, they taught us that these [shale] source rocks don’t produce,” Sheffield recalls. “Thus in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the majors began divesting in the U.S., and investing internationally again.” As a result, the acquisition of acreage and assets from the majors was a first step in the indies’ rise.

“The rise of the Apaches, Devons, Nobles, Pioneers, and Anadarkos, which resulted from buying the assets of the majors, then allowed the indies to develop their own strategies,” Sheffield goes on. “Firms began finding shale—source rock—while the majors were busy competing [globally] with Chinese and Indian firms.” Now, however, the majors are returning to the U.S. market. Irving-based ExxonMobil, for example, bought the large, Fort Worth-based gas producer XTO Energy. BHP followed suit with the purchase of Houston-based Petrohawk Energy. Chevron snapped up Pennsylvania-based Atlas Energy.

From 1997 to 2005, Pioneer had been acquiring international assets in countries like Argentina, South Africa, and Tunisia. But Sheffield saw how the political climate shifted dramatically following 9/11 and the Iraq war. “It has become riskier around the world,” he says. “We stopped sending employees and families internationally about six or seven years ago. Now the Devons and Apaches are selling off international assets, and re-focusing on this great shale resource that we have.”