You don’t have to remind Beth Van Duyne that the HP Byron Nelson Championship, the world’s most successful professional charity golf event, is preparing to undergo some big changes over the next few years.

In fact, it might be better if you didn’t.

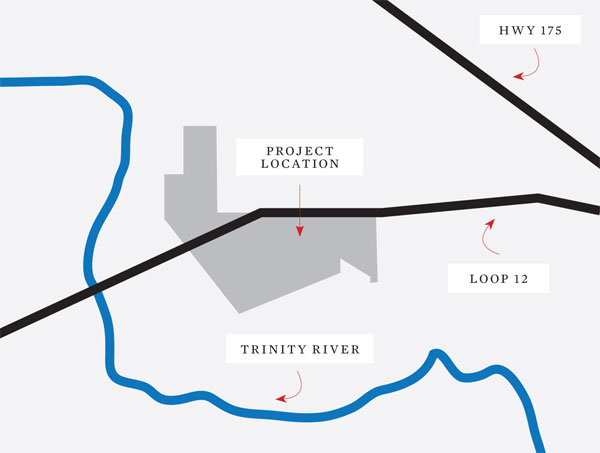

The Irving mayor knows full well that these changes will include a new title sponsor and, most likely, a new site for the PGA tournament at the future Trinity Forest Golf Course—a 400-acre former landfill about 10 minutes south of downtown Dallas, east of Interstate 45 along Loop 12.

The Trinity Forest project, Van Duyne has learned, is a $50 million, publicprivate partnership between the City of Dallas, local corporate giant AT&T, and a privately funded nonprofit foundation. She’s aware the project also includes such players as Southern Methodist University, the junior golf program called The First Tee of Greater Dallas, legendary Texas golf architects Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, longtime Dallas development whiz Jonas Woods, and local PGA Tour player Harrison Frazar.

The reality of the probable move still smarts, in part because of the way Van Duyne was told about it. Most hurtful was the blinking light that appeared on her office phone last year, mere hours before a Friday, Nov. 30, news conference at Dallas City Hall to trumpet the ambitious new golf initiative. The light told her she had a voicemail message—a very brief one, it turned out, from Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings. Said Rawlings, somewhat mysteriously: “Mayor, you should give me a call on a press conference we’re holding.”

It was Van Duyne’s first “official” warning that Dallas was aiming to snatch the Byron Nelson from her city. “I did not have notification ahead of time,” Van Duyne recalls. “I was caught off guard.”

Still, she knew something was up. Elected Irving mayor in 2011, Van Duyne had been told by the Salesmanship Club last summer that, with the pending departure of Hewlett-Packard Co. after the 2014 tourney, the club would be searching for a new title sponsor for its PGA Tour event. Later she also learned that Dallas- based AT&T, which has a major presence in Irving, had agreed to be the new tournament sponsor, starting in 2015.

But up until the day before the news conference Rawlings was calling about, Van Duyne was unaware that the City of Dallas had committed to help fund this new golf-course project, with the stated goal of taking the Byron Nelson tournament away from Irving.

That word didn’t come through official channels, but in casual conversation with Nelson tournament director Jon Drago and Mike McKinley of the Salesmanship Club. When the pair happened to run into Van Duyne at a business luncheon at the Fairmont Hotel, Van Duyne remembers, Drago and McKinley “pulled me aside and told me about the press conference.”

Still reeling from the news, the mayor next attended a previously scheduled, Thursday meeting with AT&T executive Holly Reed. Reed also told her about the news conference that was scheduled for the following day, and about AT&T’s role in it.

When she heard the cryptic message from Rawlings the next morning, Van Duyne felt betrayed by the City of Dallas.

“From Day One, we have been partners with the City of Dallas. The mayors of Dallas and Arlington, Fort Worth, and Irving agreed that we were not competing with each other,” Van Duyne says evenly. For example, “We have called each other when a company was trying to get a better deal by pitting one city against another.”

But the Trinity Forest situation, she says, was handled differently: “This seems to be the aim of taking a golden nugget from one [local] city to another city.”

Rawlings, for his part, rejects any notion of an untoward deal—or of broken protocol. And he seems surprised when told about Van Duyne’s ruffled feathers.

“She has never said that to me,” the mayor says, sitting in his modest office overlooking downtown Dallas. “I would be happy to talk to her about that.”

The idea of building that course, it’s clear, has been driven from the beginning not by the City of Dallas, but by one influential corporation, AT&T, which is seeking partly to enhance its influence in the professional golf world. It was the corporation that identified the golf-course site initially, then persuaded the City of Dallas to get on board. And, to help finance the deal, the project organizers are appealing to the same sense of “civic-mindedness” that helped raise hundreds of millions of dollars for Dallas’ AT&T Performing Arts Center during the last decade.

Throw in longstanding complaints about the Nelson’s golf course in Irving, and it’s clear that Van Duyne and her city never had a chance.

A PASSION FOR GOLF

The idea for a premier golf course on Dallas city land began taking shape in the fall of 2011, with the fertile minds and considerable political skills of AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson and Ron Spears, the company’s senior executive vice president.

AT&T, which moved its corporate headquarters to Dallas from San Antonio in 2008, has worked hard to be a good corporate citizen here, putting its name on the performing arts center in the Dallas Arts District, for instance.

But golf is the telecom giant’s main passion. The company already is the title sponsor for two PGA Tour events: the iconic AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro- Am in February, and the AT&T National in Washington, D.C., in June, which benefits the Tiger Woods Foundation.

AT&T also is one of three sponsors for the Masters Tournament telecast on CBS and ESPN. It also sponsors a Champions Tour event in San Antonio, although its contract will expire in 2014.

In addition, Stephenson himself occupies two powerful and prestigious positions in the world of professional golf. He is a member of Augusta National Golf Club in Augusta, Ga., where the Masters Tournament is held each year, and a member of the influential PGA Tour Policy board, which helps set professional-golf policy and, more important, Tour dates.

By most accounts, the cost of AT&T’s Trinity Forest brainchild should total around $50 million, of which the City of Dallas has agreed to contribute in the neighborhood of $12 million. That figure is not an absolute cap, Rawling says, but close to what Dallas will pay for work including environmental remediation. Because of a state order, remediation would be required for any commercial use of the old landfill anyway.

AT&T will kick in $2.5 million to expand various hike-and-bike trails in the area. And SMU, which has committed to moving its men’s and women’s golf programs to a to-be-constructed practice facility at Trinity Forest, will contribute a “multimillion amount,” according to Rawlings. Frazar, the Tour player, pegs the amount at $5 million, while SMU spokesman Brad Sutton says the figure is still being worked out.

The key to making the deal succeed, though, will be selling private memberships to join the Trinity Forest golf club. Currently surrounded by churches, used car lots, and homes whose windows are protected by metal bars, the South Dallas site already is staked out for the start of construction. That’s likely to happen later this year, following expected final approval by the Dallas City Council on April 24.

To date, Frazar, development expert Woods, and others connected with the project have held a series of face-to-face meetings with local individuals and companies, asking them to join the exclusive new club at a so-far-undetermined, six figure initiation price.

“We don’t have a final price yet to give people. But everybody understands it will be above six figures. Somebody has to pay for this,” Frazar says. “We don’t know the final price of construction. But we will sell more memberships if we need more money, or sell them for more money if we need to raise more.”

Of the first 50 people he and Woods approached in Dallas to be members, Frazar says, only one turned them down: “The rest were an emphatic yes. They are ready to do it now.”

“It a very untraditional sales pitch,” says one person who has seen the presentation in person. “There are no brochures or websites to view. They’re pitching it as a great opportunity to help Dallas. None of these people need another golf club to join. But they are helping, just like people helped the Arts District.”

FIRST TEE GROUP WANTED

Frazar, who calls himself an “unpaid volunteer consultant” on the project, says he’s spending his own money to join the club. Rawlings, too, says he is a prospective member: “I want to keep that separate from my mayor duties. But when I’m no longer mayor, I certainly will look at it with interest.”

With 100 commitments in the bag, each with a ballpark $150,000 initiation fee, organizers say they’re counting on $15 million so far. They’ll need a total of $20 million for the city to kick in its contribution and for ground to be broken on the project.

Says Frazar: “The first few cars are always easiest to sell, the next 200 are more difficult. But I’m very optimistic we will get this done.”

To cover the educational and junior golf aspects of the venture, AT&T’s Spears and others approached the First Tee of Greater Dallas group. Their message: the junior-golf program was wanted for the Trinity Forest development.

“We’d heard rumors through the golf grapevine that we might be included. But we really didn’t know how to process the information,” says First Tee managing director Chuck Walker.

“Last fall, Jonas Woods called me and explained the entire plan and how we would be included,” Walker continues. “We are honored they had seen our work and felt we were worthy to be included in this plan.”

The money to construct a lavish First Tee facility at the site will come from the nonprofit foundation, which will be funded by membership contributions. First Tee, the SMU facilities, and a large practice area will be located on one side of Loop 12, with the 18-hole course on the other side. The two sides will be joined by a cart path beneath the freeway.

The course is being designed not only as a private enclave, but as a facility that will be large enough to host championship golf events and upscale charity tournaments. Besides the Nelson, the organizers reportedly hope to lure other major PGA events including the U.S. Open, the PGA Championship, and the Ryder Cup.

One legal element that could threaten relocation of the Byron Nelson tournament to Trinity Forest involves the tourney’s current venue, the Four Seasons Resort and Club in Irving. A contract signed in 1999, at the height of the tournament’s popularity, legally binds the tournament there until 2018.

However, Four Seasons officials don’t sound like they’re looking to draw a legal line in the sand.

“The Four Seasons has been a wonderful host to the tournament, and a great partner with the Salesmanship Club and HP,” says Luis Argote, the resort’s general manager. “In the end, common sense will prevail. We understand they have to raise money for their charity.

“We can replace the business,” Argote adds. “But this was also an economic spillover event.”

PARTNERS SOUGHT

The pairing of Spears—a 64-year-old West Point graduate who declined to be interviewed for this article—with the 42- year old Woods, a Texas native and selfdescribed golf junkie, may seem unusual. But the two have emerged nonetheless as the development’s driving figures.

Woods, who helped develop Dallas’ American Airlines Center and Victory Park projects during his time with Hillwood, has been involved in a variety of golf-related ventures. He’s now a principal at his own company, Dallas-based Hayman Woods.

“It’s a very exciting project to be involved in because of the size and scope,” Woods says of Trinity Forest. “It will be a golf course like nothing Dallas has ever seen.”

As they began envisioning the project’s scope in late 2011 and early 2012, Woods and Spears realized they would need partners—a lot of well-heeled and politically- or community-connected partners.

First and most important was the City of Dallas, on whose abandoned land the future project sat. Poring over public records, Spears had discovered that the city was the site’s legal owner—and that the land would require remediation before anything could come of it commercially.

As it happened Rawlings had come into office preaching the development of South Dallas, which he considers an untapped jewel. Shortly after making his landmark GrowSouth speech in February 2012, the mayor received a call from Spears, who wanted to talk about a new southern Dallas project.

“I am always eager to talk about southern Dallas projects, and it lined up with so many of my goals,” Rawlings recalls. “It was very easy to see the beginning of the idea, and to be able to get the idea accomplished.”

Spears and, later, Woods, kept Rawlings informed about the project’s progress. The mayor eventually brought in City Manager Mary Suhm and staff to find out how much money and other resources the city could commit to the deal.

Then, late last spring, the project received a “lucky” break.

RETURN TO TOURNEY’S HEYDAY

Before last May’s 2012 HP Byron Nelson Championship, HP executives told Salesmanship Club officials that they would not be renewing their title sponsorship when it expired in 2014, ending a 12-year relationship.

For any modern PGA Tour event intent on raising money for charity, having a title sponsor is crucial. It’s especially vital for the Salesmanship Club, which provides most of the funding for the charity it owns and operates, Salesmanship Club Youth and Family Centers, in North Oak Cliff.

“We don’t raise money for charity; we raise money for our charity. That’s a huge difference,” former club president Frank Swingle said in a 2009 article about the tournament in D CEO magazine.

Sensing the opportunity to support and help dictate the future of the Byron Nelson tournament, AT&T moved quickly. It didn’t take long for Spears to connect with Drago, the Nelson tournament director, and with other Salesmanship Club officials.

“The business we’re in is raising money for our charity,” Drago says. “It’s not the easiest thing to find a title sponsor, especially in this economy.’

So, shortly after losing HP, Drago and the club not only had a new title sponsor, but one of the most successful and powerful corporate golf sponsors in the country.

However, AT&T wanted something in return for its newfound love of North Texas golf. So when it signed the contract to become the Nelson’s title sponsor in 2015, after HP departs, AT&T insisted that the agreement run for just two years. Although that’s an unusually brief timeframe for a large corporate sponsorship, the timing fit neatly with the construction period for the new South Dallas golf course, which is scheduled to open in the spring of 2016.

According to several sources who asked to remain anonymous, AT&T also delivered a very direct message: “They made it very clear that if the tournament didn’t move to the Trinity Forest course, there would be no title sponsorship,” one insider says. “That’s why it was only for two years.”

Charles Spradley, president of the Salesmanship Club, had no problem with AT&T’s two-year contract requirement. “That’s very savvy and very reasonable,” he says.

Since 2003, Plano-based EDS had sponsored the PGA Tour event, which became the template of successful pro-golf events after aligning with golfing legend Byron Nelson in 1968. Over the years the Nelson raised big bucks and earned hundreds of thousands of loyal fans—as well as the loyalty of A-list pro golfers.

But with the retirement of longtime EDS executives, not to mention the 2006 death of Nelson and the acquisition of EDS five years ago by HP—which effectively meant the corporate headquarters was in California, not North Texas— things had recently changed at the Nelson tournament. And not for the better.

One other culprit, often expressed loudly and in public: the Tournament Players Course at the Four Season Resort, where the Nelson has been played. A vocal minority of touring pros said the TPC lacked imagination and was poorly designed.

The course had been there when the Nelson moved to Irving from Dallas in 1983—the tournament actually began its life in the 1960s in Oak Cliff—but underwent a total renovation in 2011 that cost the Four Seasons owners $9 million.

The renovation earned the plaudits of many players and fans, but not enough of them to quell the criticism—or to bring elite players back to the tournament after Nelson’s death.

“Anytime you enjoy less-than-stellar reviews, it’s a great thing to reset the narrative,” Spradley says.

Frazar, the pro golfer, who served as a player consultant on the TPC makeover along with local architect D.A. Weibring, heard his share of criticism about the TPC course from his fellow PGA Tour players.

“I thought D.A. did a great job on the course, and I thought we made the course better,” Frazar says. “But whenever you get a vocal minority, you can’t shake the negative feeling, and it becomes a poisonous

situation. There was a feeling you couldn’t elevate [the status of the tournament].”

Luckily AT&T was all about elevating the Nelson’s status, and didn’t hesitate to share that with Rawlings. Says the mayor: “We want to get back to the tournament heyday, when we had all the top players.”

With the new Trinity Forest course, and the backing of the telecom giant, Rawlings and others associated with the project believe they can do just that. “The feel will be different, but we can raise more money for charity by leveraging our sponsors,” Rawlings says.

Meantime, those invested in the tournament’s success are watching all this with something like nervous excitement. “If you’ve ever moved into a new office or a home, you always have a bit of trepidation,” says a former president of the Salesmanship Club. “But I think this will work

out best for the club and the charity.”

Not surprisingly Irving Mayor Van Duyne, on the other hand, is not nearly so sanguine. Van Duyne says the tournament pumps $40 million annually into her city. Irving Convention and Visitors figures show a $4.8 million publicity value from the Nelson, including four days of national TV exposure, not to mention a nearly sold-out week of business for the Four Seasons Resort.

“We have all been associated with projects which we announce with great excitement and favor, only to see them fail in the end,” Van Duyne says.

“Of course, we wish Dallas all the success in the world with this,” she adds with a hint of sarcasm. “But we will continue to execute an outstanding tournament here in Irving.”