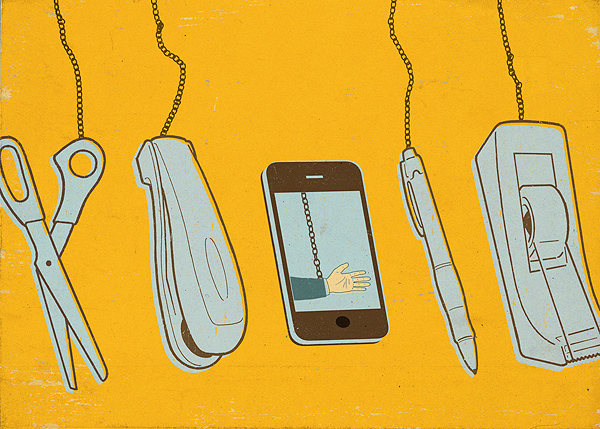

That memory of receiving your first company-issued Blackberry or cellphone may not be as quaint or nostalgic as Ralphie’s joy at receiving his Red Ryder air rifle in “A Christmas Story.” But it soon may be, thanks to the “Bring Your Own Device,” or BYOD, phenomenon. Allowing employees to bring their own mobile devices—smartphones, tablets, laptops, notebooks, etc., to work and use them for business purposes is rapidly becoming the new normal.

According to a November 2011 survey by Citrix on what companies are doing to manage the growing role of personal devices in the workplace, 25 percent of companies support the use of personal devices for business purposes. Good Technology, a Sunnyvale, Calif.-based mobile security firm, maintains the adoption rate is even higher, saying that nearly 75 percent of companies support BYOD.

No less an industry leader than IBM even adopted a BYOD policy in 2010. Although the computer giant still provides Blackberrys to about 40,000 of its 400,000 employees, another 80,000 workers are accessing internal IBM networks with smartphones and tablets, most of which were bought by the employees themselves.

The popularity of the BYOD approach is easy to understand from both the company and employee perspectives. After all, most people own a smartphone and a laptop, notebook, or tablet, and it’s only natural to want to use a device that you prefer and are comfortable with—in many instances newer and superior to the “yesterday’s model” mobile devices that might be issued by a company IT department. Besides worker satisfaction and morale, there’s also convenience: few people want to have to carry around two smartphones (one for work, one for personal use). The use of VPNs and corporate-sponsored anti-virus software has also made it easier to blur the lines between business use and home use of a given device, resulting in greater productivity. For companies, a BYOD program helps the bottom line, saving the business on technology costs as employees pay not just for the device itself, but the voice or data services as well. According to Good Technology’s “State of BYOD” report, “50 percent of companies with BYOD models are requiring employees to cover all costs—and they are happy to do so.”

So, with companies like IBM, Procter & Gamble, Kraft Foods, and many others embracing a BYOD model, what could possibly go wrong with all of those iPhones, iPads, Android phones, and other devices making their way in the workplace? Plenty, says employment law specialist Mark Shank, a partner at Gruber Hurst Johansen Hail & Shank in Dallas.

If an employee leaves voluntarily or is terminated, retrieving company data on his or her personal device can be problematic. “Once an employee starts using devices they own for work, confidential information ‘lives’ on their devices,” Shank says. “After quitting or being fired, the employee may take the position they do not have to give their former employer access to the device.”

Companies may be at risk of seeing trade secrets walk out the door and into a competitor’s hands, all because of an employee’s dual use of a device. Conversely, a new employee bringing his own device may have confidential or trade secret data on it from his previous employer. The fact that a company even has a BYOD policy permitting a worker to store and access such protected information could also come back to bite it, making it harder to prove misappropriation or violations of statutes like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

Another potential legal pitfall for companies with BYOD work environments stems from the very flexibility that mobile devices provide.

When non-exempt employees are allowed to use their smartphones and tablets to conduct work-related activities “off the clock,” the result can be possible violations of wage and hour laws. Even if that employee uses her iPhone or other device without the boss directing her to do so, compensation for time spent making work-related calls, or reading or sending work emails, may still need to be paid.

As Shank points out, “The law of when the workplace starts is quite complicated, but there have been cases where courts have been asked to hold that the workplace starts when the first work is done.”

Data Breaches, Cyber Attacks

Yet another area fraught with risk for a BYOD company centers around the business’ own obligations in the event of a data breach. Storing data is a highly regulated area, with Texas and many other states imposing security and breach notification obligations on businesses that collect or store personal information like credit card numbers, Social Security numbers, and driver’s license numbers. If an employee’s dual use device is lost, stolen, or improperly accessed, an employer may have to provide legally-mandated notifications.

Certain laws, like the Fair Credit Reporting Act, require the secure destruction of certain types of sensitive information, while HIPAA mandates that covered entities at least consider encryption of personal health information. These rules still apply, even if the data is on an employee-owned laptop or tablet.

In addition, the proliferation of personal devices in the workplace increases the company’s risks of cyber attack. Employees making personal use of their device may expose themselves to malware by mistake by visiting questionable websites or downloading the wrong applications. Moreover, a byproduct of a BYOD policy is a greater variety of devices, each with its own operating system and software. Such variety can make it more difficult for a company to effectively secure its network.

Companies with a BYOD environment may also make life more difficult for themselves in the event of a lawsuit. When a lawsuit is filed, or even threatened, a litigation hold—a directive to preserve potentially relevant information—is usually issued. Collecting or preserving data for purposes of litigation can be a logistical nightmare with the variety of devices used by employees. In addition, a company using a BYOD model may not even be able to confidently say where all of its data is stored, and could be left utterly at the mercy of its employees for information that it’s obligated to preserve and turn over in electronic discovery.

In a federal court lawsuit in Minnesota against Accenture, for example, the judge ruled that data stored by employees on a remote server was under the employer’s control if the employees were able to access the information during the normal course of their job duties. And under agency law, an employer can be held responsible for the spoliation, or destruction, of relevant evidence by its employers. As a result, an employee who destroys information on a thumb drive may get his employer in hot water.

Yet another legal nightmare for employers in the murky world of BYOD concerns the still-developing area of employee privacy. Workers are using the same devices they use at work to engage in personal activities with a tremendous amount of private content, such as their personal emails, photos, user names and passwords, web surfing history, financial account numbers, and more. Although the U.S. Supreme Court held in a 2010 decision (City of Ontario v. Quon) that employees have no privacy when they’re using a company-issued device, it remains unclear if employees using their own iPhones or tablets will be entitled to privacy if they’re conducting business for an employer.

BYOD Strategies

So what can a company do to protect itself in a BYOD world? One is to be proactive. Although IBM did adopt a BYOD policy, it knew that use of employee-owned devices made it vulnerable. So it took certain security steps. For example, before an employee’s personal device can be used to access any IBM networks, IT specialists modify it so that its memory can be erased remotely if lost or stolen.

Another important step for businesses is to adopt a clearly-defined BYOD policy that sets out the rules of engagement. Although company-issued devices are usually covered by a policy that identifies what a business deems to be “acceptable use,” it’s a bit more challenging to tell an employee what is considered “acceptable use” of their own smartphone or tablet. The policy should also dictate requirements for information security and safeguarding of specific data to which the employee has had access. Moreover, the policy should address how the data on a personal device will be retrieved upon termination of employment (whether voluntary or involuntary). It’s also a good idea for the policy to require the employees to provide any passwords they use for the devices, and to update the employer if passwords are changed or if new devices are purchased. Most important, a BYOD policy should define what the company’s expectations are regarding security as a condition for allowing the personal devices to connect to the business’ network—even to the point of prohibiting certain types of data from being copied or stored on such devices.

Here’s the bottom line: Although BYOD policies are rapidly becoming the new standard practice, they bring with them significant risks for a company. And the law certainly has not kept pace with this trend toward the consumerization of IT, in which information may reside in both company-owned and personally-owned devices and travel through both corporate networks and third-party cloud computing services.

To protect themselves in a BYOD world, businesses need to educate themselves about the risks, establish appropriate policies regarding use of their data and, above all, remain vigilant.