When Dary Stone found himself out of a job in 1982 after his boss, Texas Gov. Bill Clements, lost a reelection bid, Bob Perry, a Houston homebuilder and top GOP fundraiser, offered the then-29-year-old attorney some advice. “He told me I needed to focus on just one thing,” Stone says with a wry smile. “I’ve studiously avoided doing so.”

In fact, Stone’s career path has meandered through a number of different fields—and he has excelled in each.

Along with serving as a director of Cousins Properties Inc., today he also maintains his own firm, RD Stone Interests, helps run a local wealth management concern, oversees real estate investments for Tom Hicks, and is driving development of a $250 million football field for Baylor University.

“I’m very lucky,” he says. “All of the things I’ve done in one area have sort of slopped over into others.”

This past fall, Cousins Properties’ third-party client business, which operates in Dallas and Atlanta, was sold to Cushman & Wakefield. That’s led to a shift in focus for Cousins—and Stone, who’s now concentrating on acquisition and development pursuits in Texas.

He works out of an office in Hicks Holdings’ suite at the Crescent in Uptown. Hicks calls his colleague “remarkably talented.”

“Certain people can multitask, keep all the balls in the air—Dary is like that,” Hicks says. “He’s also a great communicator, and he’s very competitive. He has basketball games at his place on Saturday mornings, and he gets the best of most guys, even if they’re better athletes.”

The son of an FBI agent, Stone moved with his family to Dallas from Washington, D.C., in 1968, when his father became chief of the Southwestern Institute of Forensic Science. It was the middle of his sophomore year. After attending integrated schools out east, he found himself at the lily white, affluent Hillcrest High. On the first day of classes, Stone noticed a group of girls wearing leather jackets emblazoned with “Panadeers,” and mistook the drill team for a gang—“a very attractive girls gang, but still a gang,” he says.

Stone went on to attend Baylor University, then Baylor Law School. He was just 23 when he graduated and took a job at what’s now Fanning Harper Martinson Brandt & Kutchin PC. Within weeks, he was approached by a friend to help with the Texas gubernatorial campaign of Bill Clements, founder of SEDCO, once the world’s largest offshore drilling company. Stone thought it would be a good way to help build his law practice, took a leave of absence, and signed on.

His job was to go into towns like Midland or Abilene or McAllen and call on people in Clements’ Boy Scout or TIPRO (Texas Independent Producers and Royalty Owners) directories and get them organized into groups. A campaign event would be held, and Stone would move onto the next burg. After winning the primary against Ray Hutchison, Clements asked Stone to become his personal assistant during the general election, and deputy general counsel in his administration. Among other things, Stone was in charge of pardons and paroles. “You couldn’t get out of prison without going through my office,” he says.

Clements loaned Stone to Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign in 1980. He served as organization director for Texas, a critical state for propeling Reagan into the White House. Stone was then named to head an agency that looked after the state’s interests in D.C. “It was a cool time to be in Washington,” he says. “Jimmy Baker was chief of staff, Karl Rove was another guy who worked with us. There were a lot of ‘Texans-go-to-Washington’ guys, and it was a ton of fun.”

Segue into Real Estate

With an “Extreme Right Wing” plaque prominently displayed on the wall behind his office desk, there’s no doubt as to where Stone’s political loyalties lie. But it was a Democrat who helped him get into commercial real estate. Back when Clements was first running for governor, Stone became friends with his counterpart on Democratic opponent Steve Hill’s staff, Steve Van. After Hill lost to Clements, Van went to work for Criswell Development Co. in Dallas. When Stone found himself in a similar situation four years later, Van, who today serves as president and CEO of Dallas-based Prism Hotels & Resorts, helped bring Stone into the Criswell fold. There, he worked on Spectrum Center, 8080 Central, and “the big building downtown,” Fountain Place.

In 1986, Clements prevailed in a comeback bid, and appointed Stone as chairman of the state’s finance commission, the regulatory authority for state banks and savings and loans. It was during a time of profound change in the industry. When Stone began his post, there were about 240 state-chartered S&Ls; when he left, there were five.

By then, Stone had formed his own real estate firm, RD Stone Interests. His first acquisition was Spectrum Center. Knowing about the regulatory environment at the time, he brought in FADA (Federal Asset Disposition Association) as a tenant. The group took 7,000 square feet. “Ultimately, that became FSLIC, then RTC, then FDIC—and 240,000 square feet,” Stone says. “I had the only growing tenant in Dallas. That kept my mortgage current, and kept me in business.”

In the early 1990s, Stone was approached by North Carolina developer Henry Faison to do a joint venture and pursue opportunities in Texas. Faison Stone worked on a number of projects in Austin, then won a huge prize: the operation and management of Las Colinas, one of the country’s largest master planned developments.

Las Colinas’ primary owner at the time, pension fund TIAA of New York, was looking for a firm that didn’t have any bad loans, and someone with political connections. Faison Stone fit the bill. After winning the deal, the firm went from having about 20 North Texas employees to 150. “We took over at a time when Las Colinas was a disaster,” Stone says. “Everything was posted for foreclosure, occupancies were dropping, bankruptcies were happening every day. And we had all of this land—which is the last thing you want when there’s no market for development.”

The firm aggressively pursued corporate relocations. It moved Transamerica into the iconic Williams Square, and inked several big land sales to ExxonMobil and others. Perhaps most significantly, Cousins was successful in getting zoning changes that allowed for multifamily and other non-office uses.

Faison sold his firm to Trammell Crow Co. in the late 1990s. Stone didn’t want in on the deal, as redundancies in the market likely would have left many on his team without a job. His group was hotly pursued by other suitors. Ultimately, Stone merged his company with Cousins Properties Inc. of Atlanta.

“A lot of times the story of a private entrepreneur who sells to a public company is a short, ugly one,” Stone says. “But the story with Cousins, because it’s such a terrific company, has worked out fantastic.”

Chairing the Board of Baylor

Stone’s influence has also extended to his beloved alma mater, Baylor University. He joined the board in 2004, and served as its chairman from 2009-2011. During that time, his son, Dary Jr., was on the football team (along with Heisman Trophy winner Robert Griffin III).

During his tenure, Stone led the effort to hire a new university president—Ken Starr, famous for his independent counsel investigations of then-President Bill Clinton—and the capital campaign for the school’s new football stadium. Stone is still involved in that project, which is set to debut in 2014.

Current board chairman Richard Willis, CEO of Navarre Corp., says Stone’s varied experiences have benefited Baylor. “He was very good at bringing practical solutions, making sure we were flexible, and educating the board on best practices,” Willis says. “And without Dary, we wouldn’t have made progress on the stadium. He raised more money for us in six months than we did in four years. He’s always willing to fill whatever role the university needs him to fill. I think he’d dig a ditch for us if we asked.”

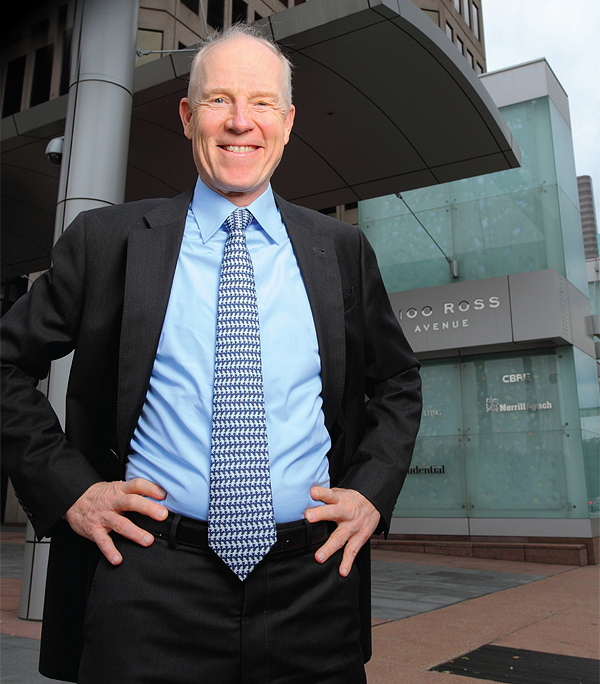

Today, Stone spends most of his time on projects for and with Hicks, and on pursuits for Cousins, whose local holdings include 2100 Ross, a 33-story downtown skyscraper the firm purchased in August. He continues to work with the third-party team he first built at Cousins 20 years ago, but this time as a Cushman & Wakefield client.

Stone, whose “aw-shucks” manner stands in contrast to the many chest-pounders in Dallas commercial real estate, says his success is more a fortune of circumstance than anything else. “I’m a pretty average talent in all things,” he says. “I worked in politics when the state was shifting from Democrat to Republican, in banking during the S&L crisis, in real estate during a time of unprecedented change and growth, and for Baylor during its renaissance. I’m really just a product of being part of the greatest city and state I can imagine.”