Trouble is, those customers also have more options than they may have had during Ullman’s peak-performance years of 2004-2007. “J.C. Penney had a window from 2005-2007 when Kohl’s was really just getting going and Macy’s was trying to offer merchandise for a higher-end consumer,” says Rob Wilson, founder and president of San Francisco-based Tiburon Research Group. “J.C. Penney was running their company more efficiently. They had infused new products in the stores. But Macy’s had also given them an opportunity to attract disgruntled Macy’s customers. That came to an end when the economy turned south and Macy’s came back more aggressively.”

That’s an understatement. Macy’s stock value has quadrupled since hitting a low of under $6 a share in 2008. Kohl’s has seen similar gains. The discount chain upped the quality (or, at least, the name appeal) of its apparel to try and compete with department stores on both design and price. It has worked. Since 2008, Kohl’s has boosted revenue by almost $2 billion annually, to $18.4 billion—surpassing J.C. Penney. The company’s stock, though still well off its 2007 highs, has also outperformed J.C. Penney’s on this side of the recession.

Therein lies the problem for J.C. Penney. Ullman has refocused the in-house brands, and has a happier, better-managed work force pushing them, but the company hasn’t differentiated itself from its rivals either by creating buzz around its own brands or by bringing enough of a new kind of customer—a younger customer—into stores for all those new offerings. J.C. Penney’s core customer has, for decades, been a woman aged 35-55, who has between $35,000 and $100,000 in household income. And it still is. Of the under-35 crowd, Ullman says, “We are in the early days of learning about them.”

SO, WHAT CAN RON JOHNSON DO? If an executive from Apple is supposed to know anything, it is what the kids (under 35 counts, right?) want these days. And, anyone at Apple—where products launch with a similar look, feel, and level of hype—should have a solid understanding of branding. But Apple products cost a lot of money. The average price for a women’s blouse at J.C. Penney is $15. And, besides, is it fair to compare a shiny iPod to a pair of cotton underpants? “This guy was selling iPads, iPods, and iPhones over the last few years,” says Tiburon’s Wilson. “I think you and I could have sold those pretty well.” More telling, then, than his work at Apple is Johnson’s work at Target. It was Johnson who, as a senior merchandising executive at that discount retailer, brought in big-name, modern designers like Michael Graves, convincing them to “democratize” their designs for the mass market. Before Johnson came along, Graves was selling teapots for almost $200. Today, his sharp-looking products are priced under $20 on Target shelves. Cool designer names. Everyday prices. If Johnson can deliver on that at J.C. Penney, its revenue woes may be over.

3 | TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT

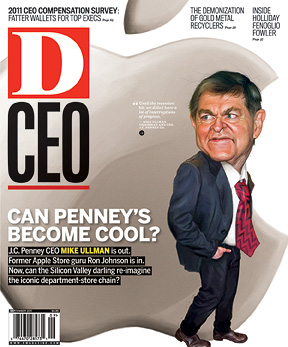

He is the old man. The 64-year-old man in charge of the old brand. The 109-year-old brand. He studied engineering for a while because he was 10 when Sputnik launched and engineering became cool then. Cool, daddy-o. That’s what he said at the time. Probably. Because that’s what an old man would say. It’s not what the cool guy, the cool 52-year-old guy from the cool computer company with the bitten-fruit logo would say. But here’s the funny thing: Ron Johnson may have pioneered the Genius Bar, but it’s Mike Ullman, that old daddy-o, who has led J.C. Penney to innovative uses of technology in its stores.

When Ullman asked the headquarters staff to name the 10 things they didn’t like about the company, one of the responses he got told him that J.C. Penney needed to spend more on new technologies both at the home office and in the stores. So they spent. A lot. About $200 million on in-store terminals that can access the Internet. Can’t find an item or a size? You, or your salesperson, can check the company’s online store using a 42-inch touchscreen.

Oh, and speaking of that online store, guess which brick-and-mortar retailer is the leader in online sales, with $1.5 billion in revenue? The one run by the old man. J.C. Penney was also the first big-box retailer to let people buy products directly through its Facebook page.

Innovations like that landed J.C. Penney at 65th among all major companies in Information Week’s annual ranking of the 500 top technology innovators. The next retailer on the list was Wal-Mart, nearly 20 spots below. Neither Macy’s nor Kohl’s made the list. “One of the reasons we’re so successful in some of the newer things we’re trying is because we invested a lot in technology,” Ullman says.

SO, WHAT CAN RON JOHNSON DO? J.C. Penney’s online sales have been good, very good, but they have not been immune to the sales slump that it has been in since 2007. Internet sales have barely budged off $1.5 billion in that time. But with Steve Jobs as a mentor, you’d figure Johnson has the know-how to get them moving again. Then again, you might be wrong. Johnson didn’t run Apple’s online store. He did, however, integrate the Internet into the shopping experience at the Apple Store, including using an online form for Mac owners who planned to visit the store’s Genius Bar. Can one translate those kinds of innovations from a technology retailer to an apparel and home-goods store? Can you make J.C. Penney into iPenney? That’s anyone’s guess.

4 | INVESTOR MANAGEMENT

Oh, the irony. On June 14, 2011, the slumping stock price—an issue that had plagued Ullman’s leadership of J.C. Penney, an issue that had caused a pair of investors to buy up shares, push their way onto the board, and demand change—suddenly seemed resolved when the stock shot up 17.5 percent. The reason it went up: The company announced that Apple’s retail chief, Ron Johnson, would be taking over as CEO. Forget the employee surveys and the Internet kiosks in the stores and the European brand-name offerings and the Academy Award TV ads. All Ullman had to do to make the stock go up—way up— was quit. Capitalism is cruel like that.

Here’s another irony. Ullman also led the company when it registered its highest-ever stock price: $87.18 a share on Feb. 21, 2007. The price cascaded into the high teens during the depths of the recession, and has hovered in the high $20s until Johnson’s hire pushed it solidly into the $30s.

That languishing stock price is what drew substantial investments in J.C. Penney from Bill Ackman, who runs Pershing Square Capital Management, and Stephen Roth, chairman of Vornado Realty Trust. Together, they bought up 26 percent of J.C. Penney’s common stock last October. Both said they were doing so because they believe J.C. Penney’s stock is undervalued in comparison to the company’s competitors.

Kathleen Wailes, senior vice president of Levick Strategic Communications, says Ackman and Roth had a point. When you look at the solid, recent stock performance of Macy’s, Dillard’s, and Kohl’s, she says, “it suggests J.C. Penney is not underperforming because there is an industry-wide problem.”

So, what’s the problem? Both Ackman and Roth say it is at least in part a problem of real estate. J.C. Penney owns more than 400 of its 1,100 stores. About 550 of the 1,100 stores are in shopping malls. In the malls, J.C. Penney generates something like $150 a square foot in sales. Off malls, in its newer stores, the company has generated as much as $250 per square foot, Ullman says. That’s why many analysts have suggested that the company should shed more stores, possibly selling the real estate and pocketing the cash to fund new-store growth.

J.C. Penney already has $1.8 billion in cash on the sidelines. A store sell-off could lead to a massive remaking of the company’s retail presence. In theory, anyway. Who knows what an underperforming store in a weak local market might be worth? Who knows how much it might cost J.C. Penney to finance substantial new growth, or if it can get financing at all? No one. Not yet. And that’s why, in a research note it issued in mid-July, Morgan Stanley said the loss in share value at J.C. Penney may be a long-term problem that even Apple’s retail whiz can’t immediately fix.

Tiburon’s Wilson agrees. “After Mr. Ullman’s departure,” he says, “people will realize that it is a tough, competitive space that J.C. Penney is in and that the company probably needs to address some of their real estate issues in a much more dramatic fashion than they have to date.”

So far, no one has announced anything more dramatic than Johnson’s hire, which was plenty dramatic by itself. And that may be because Ullman has worked so well with the two so-called “activist” investors.

Things didn’t get off to the greatest start, though. Just 10 days after Roth’s and Ackman’s investments became public, Ullman and the board announced a “poison pill” plan that would seek to dilute the company’s share value and make it harder for Ackman and Roth to gain a controlling, 51-percent stake in the company. That plan could have been detrimental to the other J.C. Penney shareholders, and it could have spurred a protracted proxy fight for control of the company. But it was never put to use.

Instead, Ullman and the board calmed the waters by inviting Roth and Ackman to Plano to meet with the company’s senior executives and learn about Ullman’s five-year plan, which promises to boost revenue by $5 billion. Three months after that meeting, Ackman and Roth were invited to join the company’s board. At the same time, the company announced it was closing five underperforming stores—a move most observers took as a capitulation to Ackman and Roth. Around the same time, Ullman, who had met with Johnson in 2008 about joining J.C. Penney, went back to discuss the CEO’s role.

So, instead of an ugly fight, Ullman seems to have assuaged Ackman and Roth. Their public comments on J.C. Penney have become increasingly rare, with the exception of offering praise for Johnson. And, yeah, the price to gain that acquiescence may have included Ullman’s job. (Although, asked if the activist investors who’ve pressed J.C. Penney for change since last October had requested Ullman’s departure, J.C. Penney spokeswoman Darcie Brossart says, “Absolutely not. Ron’s appointment was part of the board of directors’ succession planning process, which Mike Ullman led.”)

Ullman has yet to publicly object to any of these developments. And, indeed, he will be 65 next year—the age when many retire. So nobody’s going to cry for Mike Ullman, least of all Mike Ullman himself—a man who has a pretty good perspective on where business success ends and life success begins. This is a man, after all, who has founded an orphanage in China—from which he adopted two of his six children—and is chairman of Mercy Ships, which sends doctors and nurses and other volunteers, like Ullman’s kids, to help people in the third world. “I’m at an age in my career where I don’t think of this all as life or death,” he says from his office on that perfect late fall day. “There are some serious things in the world that are worth worrying about. Business is something you work at, but it is not something that’s life-threatening. There are more important things.”

SO, WHAT CAN RON JOHNSON DO? Johnson doesn’t seem to have much choice about what he can do. He has to do something big, because the current J.C. Penney board appears to have signaled that it wants the share price to move substantially higher. At least that’s what it appears that Roth—whose real estate company leases several stores to J.C. Penney and who’s known Ullman since 1992, when Ullman was the CEO of Macy’s—would like. The same is true for Ackman, who has fought public battles with Target and Wendy’s and is now pushing to remake Fortune Brands and perhaps take his hedge fund public. So, maybe a “Jean-us Bar”? Or, maybe not. “I think clearly investors are going to get excited at the prospect of a new CEO coming on board,” says Wilson of Tiburon. “And Johnson will have a honeymoon period for about a year. But after that, investors will really start holding him accountable. So it’ll be interesting.