He zips past and suddenly he is gone. The man riding the Segway is gone through the doors to his office, the corner office of the executive suite of the headquarters building. He has been coming and going like this, on two wheels, at high speed, for seven years now. But in a few more months he’ll come and go no more. He’ll just go.

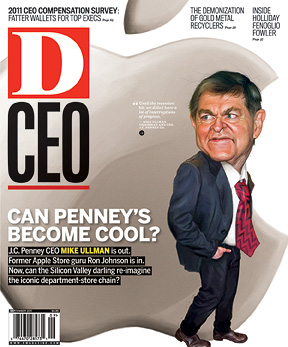

When he goes, his tenure will be reduced to a few words in some corporate history tome somewhere. It will read: “Myron ‘Mike’ Ullman, the ninth CEO of J.C. Penney Co. Inc., served between Allen Questrom, who rescued the company from certain bankruptcy, and Ron Johnson, who came from Apple Inc. and …”

The rest of those words have yet to be written. On Feb. 1, 2012, Ullman will cede his executive duties and leave the company. On his Segway, almost certainly. At J.C. Penney’s low-slung corporate campus in Plano, you see, it’s a long way from the corner office to the front door where a giant, bronze, James Cash Penney stands guard. And long distances are a problem for Ullman because of a microscopic spinal injury that limits his ability to walk. The condition helped convince Ullman to retire once, ending a successful career in retailing.

That was back in 2002, just two years before he was recruited to come to the corner office of the executive suite in the headquarters building of J.C. Penney to build on Allen Questrom’s success and add to his own business legacy. And, he did. For three years, Ullman was hailed as the man who was remaking a legendary retail brand. Not rescuing it. Not saving it. Just remaking it. Making it more nimble. More hip. Not your mom’s department store. Not any more. Now it was the department store of the future. Sephora! Mango! Er, and Liz Claiborne.

Then the recession came, and that talk went. J.C. Penney fell flat, crushed under the weight of the housing market’s collapse. The company’s core customers, Middle America, saw their mortgages go upside down, had their bills come due, and their jobs vanish. Just what in the world was the man on the Segway, the son of an industrial engineer who invented the dishwasher—the dishwasher!—supposed to do about that?

What he did was make a plan. Cut some costs. Hold the line. In this, he did well. But his competitors have done better. Macy’s, Kohl’s, Dillard’s, and the like are surging. But J.C. Penney is standing almost as still as that bronze statue of its founder. Revenues are not much better than they were last year, and they are less than they were three years ago. And the stock price is less than half its peak value from 2007.

Is all that Mike Ullman’s fault? Yes. The man in the corner office in the executive suite of the headquarters building is always responsible for these things. And a pair of activist investors has seen to it that Ullman will pay a price. The investors have pushed for big changes, the kind of changes Ullman has never made. The biggest of those is replacing Ullman, 64, with Johnson, the 52-year-old who created Apple’s Genius Bar and built that company’s retail stores from scratch.

Where Ullman brought gravitas and decades of retailing experience to a company in need of refinement, Johnson will bring techno fairy dust to magically transform a company that, despite Ullman’s efforts, is still your mother’s department store. Or, well, who knows. “I’ve always dreamed of leading a major retail company as CEO,” Johnson says, “and I am thrilled to have the opportunity to help J. C. Penney re-imagine what I believe to be the single greatest opportunity in American retailing today, the department store.”

So, as Johnson steps into his dream and Ullman wheels out of the CEO’s job, how do we assess the seven-year tenure of only the ninth man to lead a company that was founded as a single, dry goods store in Kemmerer, Wyo., in 1902? And how do we guess at what his successor will do?

Let’s start by looking at a few key areas of management. Four, to be exact.

1 | TEAM MANAGEMENT

He is seated now. The Segway is stored in the corner of the corner office. Out of the windows, it is a sunny, mild, perfect late fall day in 2010. What no one in this office on this day knows, however, is that the winds of corporate change are already blowing. In New York, a silver-haired hedge-fund manager named Bill Ackman has worked out a deal to buy options on J.C. Penney stock. He’s been buying shares since mid-August 2010. And, when his options are converted in a couple of weeks, he will hold 39 million shares, or 16 percent of all the company’s common stock. He’ll then team his shares with those held by one of Ullman’s longtime associates—Stephen Roth, chairman of Vornado Realty Trust—so that, jointly, the two will hold 26 percent of J.C. Penney’s shares. And that will be the beginning of the end of Mike Ullman’s career at J.C. Penney.

But today, there is no talk about Ullman leaving the company, about succession plans, or about the genius from Apple who thought up the Genius Bar. Today, Ullman is talking about what he did right and what he believes the company can do even right-er. And that story begins with a blank sheet of paper and a meeting with J.C. Penney’s board of directors.

“The board wasn’t sure that continuing the same things over and over again would get the company to the next level of competitiveness,” Ullman says. He’s speaking softly, sitting back in a chair at a large conference table in the middle of his office. His pink shirt is stiffly starched. But his khakis are relaxed. “So I spent two or three months here at the beginning on the premise that I had no idea what this opportunity would look like. It was a blank sheet. But I was open to the idea of starting a journey to make a different kind of company.”

At the end of his first few months, Ullman’s first actions were to change the way the company managed its people. “The opportunity here was to create an engaged team of associates and to get customers to feel more loyal,” he says. “But we also had to have a pricing proposition that allowed the company to compete right, smack in the middle between the discount channel and the higher-priced department stores.”

Some of that “pricing proposition” was already in place. When Ullman arrived at J.C. Penney, Questrom had already centralized the company, making the home office in Plano more important than it had ever been. For a century, store managers ruled individual fiefdoms. The managers decided what products to stock and sell. The home office was just there to support them. But Questrom stripped that power, centralizing buying under the direction of Vanessa Castagna, the CEO of stores and a one-time candidate for Ullman’s job. (Castagna left the company after Ullman’s hire, but has remained in Dallas.)

Centralized buying was a key step in saving the floundering company from bankruptcy, because it offered unprecedented control over costs and inventory. Just as important: Questrom restructured J.C. Penney’s massive debt and dumped the Eckerd chain of drugstores in a $4.5 billion deal. The company took a huge loss in 2003 to make the drugstores go away, but revenue that year was a healthy $17.8 billion. Still, Questrom’s dramatic changes had also produced aftershocks. He doubled the stock price, sure. But he also shuttered more than 100 stores and laid off more than 7,000 workers.

So, Ullman saw an immediate need to boost morale and better connect managers with workers. He began with a survey. All 4,500 people in the Plano headquarters were asked to name the 10 things they liked least about the company. Healthcare policies ranked high, as you might imagine. So, too, did office formalities, like referring to people as “Mr. and Ms.”—this is a company founded by the son of a Baptist minister—or having a formal dress code. The survey also showed that headquarters staff wanted a much bigger investment put into technological tools, both for them and for workers in the stores. With survey results in hand, Ullman held a rally at the home office. “We came out and said, ‘Here are the 10 things you didn’t like,’” he recalls. “And then we said, ‘So, we changed ’em all!’”

The surveying was soon extended companywide. For the first time in J.C. Penney’s history, all 150,000 employees were asked at the same time how they felt about their jobs, their bosses, their pay, the company as a whole. The first year that was done, the company’s score was 67. Basically, a C-plus. Last year, the score was 81. Let’s call that an A-minus. Or, as Ullman, the son of an engineer puts it, “An 81 is in the top decile of all companies.”

Taking a company that had been rocked by cutbacks and getting it into the “top decile” is likely Ullman’s greatest legacy at J.C. Penney. He did this even though he still had to close stores and call centers and make layoffs during his tenure. Actually, as the Ohio native says, it’s “the team’s” achievement. The credit, he says, should go to the employees who break down the 150,000 survey results into 2,200 different reports that go to every top manager in the company to give them a sense of what the employees under their charge are thinking, and what they can do to improve their scores. As a result, “We now have award-winning customer service,” Ullman says. “We even exceed Nordstrom in some polls.”

SO, WHAT CAN RON JOHNSON DO? It’s one thing—one difficult thing—to survey employees, act on their feedback, and improve their level of satisfaction with their company. It’s another to turn workers into brand advocates. That’s what Johnson has succeeded in doing at Apple’s stores. Those T-shirt wearing hipsters aren’t just fixing your MacBook Air or selling you a new iPod Nano. They’re preaching the Gospel According to Steve Jobs, conveying a passion for Apple. If Johnson can bring that spirit to a department store chain that has 1,100 locations and 150,000 employees, he will revolutionize the department store.

2 | BRAND MANAGEMENT

If Mike Ullman understood one thing when he came to J.C. Penney, it was branding. As directeur general of Paris-based LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton from 1997 to January 2002, a job that came on the heels of his three-year stint as the CEO who pulled Macy’s out of bankruptcy, Ullman had some of the best-known, best-respected, priciest brands in the world under his direction. At J.C. Penney, he inherited some of the biggest store-owned or, as they are called, “private label,” brands in the business. Arizona. Worthington. St. John’s Bay. On their own, any of those would be a billion-dollar business.

Of course, none had the cache of, say, Louis Vuitton. And that was just the problem. J.C. Penney executives weren’t giving the brands their due respect. “They were treating them just as labels,” Ullman says. His solution: Appoint brand managers to head each of J.C. Penney’s in-house brands, advocating for a mix of products and a style of store display in the same way that, say, Ralph Lauren would advocate for how its Polo brand is displayed in a department store.

Meanwhile, Ullman also brought in a new mix of brands from outside companies. There was a.n.a., a casual, modern, weekend-wear line; Nicole, a low-budget, high-fashion line for women from Nicole Miller; and MNG by Mango, a “fast-fashion” Barcelona-based line that had a limited stateside presence before opening in J.C. Penney stores. Among the biggest coups, Penney struck a deal with ailing clothier Liz Claiborne that gives it the exclusive right to sell Claiborne-branded merchandise, as well as an option to buy the brand outright in five years’ time. Nearly as important, J.C. Penney has wedged store-within-a-store Sephora cosmetics boutiques into its stores.

The company has touted all these trendy changes in aggressive advertising—J.C. Penney is among the 20 biggest advertisers in the nation, spending more than $1.1 billion in 2010—including sponsoring the Academy Awards and placing ads in Vogue. And it worked. For a while, anyway. Two years after Ullman’s arrival, the company’s revenue had surged to $19.9 billion, a $2 billion gain over when he started. The stock was also hitting all-time high prices. J.C. Penney was on a roll. “Until the recession hit,” Ullman says, “we didn’t have a lot of interruptions of progress.”

But oh, did the interruptions come. By 2008, revenue had sunk to $18.5 billion. A year later, almost another billion had disappeared from the income statement. Recently sales have been up. Slightly. “Traffic is starting to return to the stores,” Ullman says. “But customers are being very careful about how they spend their money.”