It worked. Attendance skyrocketed, and within two years of Ussery taking over as commissioner, half the league’s teams were making a profit—which is something even the NBA can’t currently claim.

Still, Ussery demurs when he’s given credit for the league’s turnaround. He says his small executive team—just seven people—deserves the real praise. His teammates, who, like most of Ussery’s friends and colleagues, call him “T,” return the compliment. “No one worked harder than T did,” says Lara Price, who worked as a marketing assistant for the CBA and is now senior vice president of business operations for the Philadelphia 76ers. “So working long hours was not a problem. He was in there with you. He believed in you, gave you the tools to succeed, and supported you.”

Ussery also supported plenty of players and coaches as he redefined the CBA into the League of Extraordinarily Failed Gentlemen. He expanded a CBA program that allowed players banned from NBA competition to play in the CBA, ramping up the drug counseling offered to those players. And he instituted the CBA Education program, which paid players’ tuition if they’d try and complete their college degrees. All of those efforts got the attention of NBA Commissioner David Stern. The CBA had previously had a tenuous relationship with the bigger league. But under Ussery, the NBA proudly came to call the CBA its “official development league.”

Stern says Ussery succeeded then for the same reasons he’s made a mark on the Mavericks: a thorough knowledge of the business of basketball. “Terdema understands the hard issues, like arena negotiations, contract negotiations, television negotiations, and collective bargaining negotiations,” Stern says from his New York office. “And he understands softer issues like branding, marketing, and also about what’s right and what’s wrong with respect to how leagues operate and conduct themselves. If I need a different perspective outside the league office, Terdema is the person I’ll call to ask for that. I consider him a friend.”

Billionaires Are Good To Work For, Even if They Never Call

Bo knows Terdema. Bo Jackson, that is. The Heisman Trophy-winning NFL and MLB all-star whose now iconic “Bo Knows” ad campaign ushered in the ‘90s. Jackson was one of the athletes that Ussery would meet and work with when Phil Knight, Nike co-founder and chairman, recruited him away from the CBA to be president of Nike Sports Management in 1993.

“I think one of the reasons why Nike called me is that, at the CBA we were successful in applying some hard-core business principles to the league,” Ussery says. “Part of that was legal—just making sure the contracts we entered into were correctly executed. But part of it was just loose ends. Tying those up was the way of getting to profitability. And when we did, we got a lot of attention from the Los Angeles Times and the Wall Street Journal. I think the folks out at Nike read some of that stuff.”

But Nike wanted more than just contract negotiations and tying up loose ends. It wanted to control its brand, as it was being represented by some of the biggest names in the sporting world. Nike Sports Management would serve partly as an agent for the athletes it represented—actively recruiting deals for them—and partly as a representative of the company itself, one that would make sure athletes’ deals didn’t diminish the Nike brand.

“The idea was that we would take the top 20 of Nike’s athletes, excluding Michael Jordan, and we’d turn them into a global brand,” Ussery says. “Alonzo Mourning, Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders, Scottie Pippin, Ken Griffey Jr., Roy Jones Jr. Guys like that. Nike was spending a lot of money to position these athletes, and they didn’t want the value of that diluted by Coca-Cola or McDonald’s or whomever else they were doing business with.”

For Ussery, the work was familiar. Mostly he was negotiating contracts, albeit on behalf of some of the most famous faces in sports, rather than on behalf of the CBA’s La Crosse Catbirds. And, at Nike, Ussery was doing that work under the tutelage of the guru of branding.

“With Phil, it is all about the brand—period,” Ussery says. “But the thing that also makes him brilliant is that he not only had phenomenal entrepreneurial horsepower, he was also equal parts deeply intellectual and creative. And he had a phenomenal sense of timing about what was hot and why it was hot.”

Unfortunately, the NCAA felt Nike Sports Management was a little too hot. It ruled that the entity was no different than any other sports agency. That meant the entire company would be subject to NCAA rules that try to separate sports agents from student athletes. And that meant Nike would not be able to reach apparel deals with individual universities.

The thought of banishing the swoosh from the jersey of, say, the Syracuse Orange, was too much to bear. So Nike dismantled its sports management group, leaving Ussery to float around the company.

And that’s when Ross Perot Jr. called. Perot was the newly minted majority owner of the Dallas Mavericks in 1996, and his plan for profitability was to get the team a new arena right in the middle of a planned mixed-use development in downtown Dallas. Perot needed help executing that plan, and he called NBA Commissioner Stern to ask whom he should consider for the Mavericks’ presidency. Stern told him to call Ussery.

On paper, Ussery’s experience—in law, government, and sports—made him the perfect choice for an owner who wanted to convince city voters to pass a bond offering to help build a new, multimillion-dollar arena. And in practice, Perot got exactly what he wanted from Ussery. Voters eventually okayed a $150 million bond offering. The Mavericks and the Dallas Stars fronted the additional $300 million it cost to build American Airlines Center.

Ussery got what he wanted, too. “As a guy who had done some transactions work and had been around sports and entertainment, the Mavericks job was kind of the culmination of my career at that point,” Ussery says. “I was getting to use disparate areas of expertise and bring them together in one big project. Not a lot of guys get to be involved literally from the beginning of selecting an architect and designing an arena. Plus we had to talk to voters because we had a bond election. So for me there were a lot of moving parts and I really liked the unpredictability.”

Things got even more unpredictable after the AAC broke ground. Perot was making it clear he wanted to sell at least a portion of the team. So Ussery suggested he contact Mark Cuban.

“I didn’t know Mark,” Ussery says. “But I knew of Mark.” He knew of Mark from the advice of Jonathan Miller, the current CEO of digital media at News Corp. Ussery had become friends with Miller when Miller was working for Barry Diller, whose IAC/Interactive Corp. had negotiated a TV deal with the Mavericks. “I talked to Jonathan and told him that we were looking for a guy with some pop,” Ussery recalls. “He told me about Mark.”

A year before the AAC opened, Cuban bought controlling interest in the Mavericks. And rather than clean house, he decided to keep Ussery on. “Terdema is very smart,” Cuban says. “He was doing a great job with the Mavs, and I saw no reason to change that.”

No one was more surprised at that news than Ussery. “In this business usually when there is a sale of a team, the team president is fired,” Ussery says. “So I thought for sure I’d be going back to Southern California. But Mark was great. He said, ‘Hey, I’ve heard good things about you, so if you want to stay you are welcome to stay.’ It’s been a hell of a run since then.”

But it hasn’t been a profitable run. And there’s the rub with Ussery’s job. He’s the CEO of a team that has, in many ways, been a phenomenal success during his tenure. The team had 240 wins and 550 losses in the 1990s. In the 2000s, the Mavericks have flipped that record, putting up 50 wins per season for 10 straight years, this season not included. That, and an arena that, even nine years on, is considered one of the best in the NBA, has helped boost revenues. So, too, have a number of major deals with corporate sponsors like AT&T and Cadbury-Schweppes. The Mavericks brought in about $60 million in 2000. Last season they boosted revenue to $154 million.

But while the Mavericks are raking in money, they aren’t making a profit. The team lost a total of $273 million between 2000 and 2009. That’s according to a lawsuit filed last year by Hillwood Investment Properties III Ltd.—aka, Ross Perot Jr. The suit alleges the team is close to insolvency, a claim that Cuban—whose net worth is still estimated at nearly $3 billion—has dismissed as ridiculous. But Cuban admits that the team has been consistently operating in the red.

From Ussery’s standpoint, this contrast between on-court success, increasing revenues, and net losses, is one of the unfortunate realities of professional sports.

“You can look at whatever benchmark you want,” Ussery says. “Overall revenue, revenue per head, revenue per account, entertainment value, value per dollar—use whatever metric you want to use. By any of them we are exponentially better today than we were 10 years ago. Without qualification. But the problem is that in sports, more than any other business, there is always the next guy who is going to get you the championship. Now, he’s going to cost you $25 million that you didn’t budget for. But he’s going to get you a championship. And so, in this business, whether it is the New York Yankees or some of the teams in our league or in other sports leagues, if you want a championship, you pay those guys. And it is always difficult on the revenue side to keep up with the lack of predictability on the expense side.”

Consider the numbers. Last year, the Mavericks brought in $154 million, according to Forbes magazine, which rounds up the finances of major league teams each year. The team spent $99 million on player salaries. Beyond that, it also had to fly the team around the country, pay the coaching staff, pay Ussery and the other 120 people who work for the team, and service the debt the team still owes for what it spent to build the AAC. That led to what Forbes believes is a $17 million loss. Perot may be calculating it differently. His lawsuit puts the team’s fiscal 2009 loss at $50 million.

Ussery’s job in the organization is to direct the operations team that puts on 44 home games per year; manage the corporate sales team that deals with big sponsors like AT&T; manage the ticket sales staff; and negotiate all the team’s major contracts. He also consults on player and coaching staff salaries, but those expenses—by far the largest on the team’s balance sheet—are ultimately up to Cuban.

That begs the question: If you’re the boss of an organization where you are responsible for revenue, but where you have no control over the biggest expenses, do you just focus on revenue and forget about the bottom line? And, if so, is it liberating not to have to worry about profits and losses?

Ussery, who is already a deliberate, quiet speaker normally, takes an extra long pause to consider those questions. “We do focus on both sides of the ledger,” Ussery says. “And we run a very, very lean operation. Believe me, it can get very intense around here. Mark is acutely aware of what he is spending. But Mark didn’t get in this to make money year in and year out. This is professional sports. That’s like saying you’re going to Hollywood to produce movies because you really want to make money. It was about, for him, taking an asset that, in his mind, had been diluted and damaged, but that he loved as a fan, and bringing it back to life—times two—and trying to bring a championship to the city. And he said from the beginning that he was willing to lose money to get us there. But he never said he came into this for positive cash flow. This is the sports business. This is not the business you come into to generate positive cash flow. It’s just not. I can’t name five teams in our league that do it.”

So, the bottom line about the bottom line: Cuban is willing to accept losses (even if Perot, who still owns 5 percent of the team, is not) to get a championship, but that’s no relief to Ussery, who is under constant pressure to generate more and more income to try and keep up with the price of success. And, yet, the really strange thing about Ussery’s management challenge is that he pushes his sales teams—both the ticket sellers who work in a call-center-style setup in Deep Ellum, and the corporate sales team—to ignore success. Fifty wins a season? Forget it. Playoffs? In the immortal words of football coach Jim Mora, Don’t talk about playoffs.

“If the team is doing well and the phones start ringing more, that’s great,” Ussery says. “But we don’t market to that. We think that what we are selling is three hours of fantastic entertainment. The basketball is the centerpiece of that, but a lot of other things go with it, too. So we want our people to stay focused on what they can do to convince people that this is the place to be, and not focus on the team’s performance. Because, you know, when a team is doing well, people do tend to get a little lazy. You look at what happened in Miami. They thought, we have Dwayne Wade, Chris Bosh, and LeBron now, and they fired their whole sales team. That is a head scratcher to me.”

Understandable. Taking away ticket sellers would be like cutting off one leg of a three-legged stool that is Ussery’s day-to-day responsibility. (He oversees ticket sales as well as corporate sales for the Mavericks, remember, as well as game-day operations for the team’s ACC events.) The ticket responsibility means he and Cuban have to strategize on how to get more people to the games, even when the economy is down like it is now. In the past couple of years, that’s meant offering tickets at discount prices. “Some people just don’t have discretionary income right now,” Ussery says. “And that has definitely had an impact on us. But we have told people, ‘We understand what’s going on out there, but we still want you to come and have a good time.’ So we have $2 tickets now and we have $5 tickets. We just want to get people in the building.”

The execution for doing that falls on Ussery, but the concept comes straight from the owner—a guy who used to sit in the cheap seats before Broadcast.com and Yahoo made him a billionaire. In the decade they’ve spent working together, both with the Mavericks and at Cuban’s HDNet, for which Ussery also serves as CEO, the pair have learned to blend their differing management styles. Cuban can be brash and brusque whereas Ussery is exacting and inspirational. Ussery “is a better communicator than I am,” Cuban admits. Still, while the two seem to mesh, you wouldn’t exactly call them pals.

“Mark is extremely intense,” Ussery says, pausing, and then reemphasizing his point. “Extremely intense. When he comes to trust you, he will give you freedom to run the business, but he’s not the kind of guy you’re going to have a casual conversation with. When you hear from him, it is almost always something focused on business. He is a performance-oriented guy. He is not an excuse guy. Mark is not a boring guy. Put it that way.”

The dot-com wunderkind is also, not surprisingly, not a phone-call guy. “With Mark, it is e-mail or in person,” Ussery says. “But it’s an efficient means of communication: ‘Here’s the issue. Here’s what we need to do.’ To the point. But, really, I think I’ve only talked to Mark on the phone maybe twice in the last three years. One of those calls was before the NBA All-Star game [at Cowboys Stadium in Arlington]. I was standing at center court, and Mark was somewhere outside the arena, in traffic, with thousands of other people. He had to be on television, so I was trying to find him. He was really apologetic about it. He couldn’t believe all the people that were out there.”

Eventually Cuban made it inside the stadium, as did 108,713 others. A framed certificate from Guinness World Records, recognizing the largest crowd to ever witness a basketball game, hangs on Ussery’s fabric-covered cubicle wall. It is a testament to the lead role Ussery took in putting on the biggest event in the history of the sport.

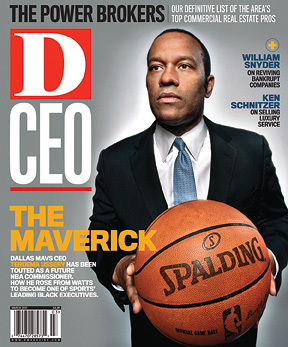

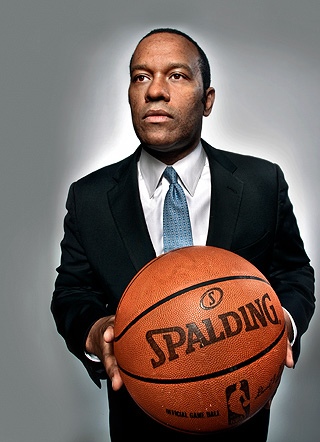

It’s that accomplishment, along with his turnaround of the CBA; as well as his tutelage under the master of branding and a key NBA partner, Phil Knight; plus the fact that he has successfully worked with one of the most cantankerous—and fan-friendly—owners in the league, that has led to speculation that Terdema Ussery could succeed David Stern when the 68-year-old finally retires. Stern has said publicly that he thinks Ussery is more than capable of taking over the job. But for his part, Ussery isn’t campaigning for the commissioner’s post or anything else.

“I’ll play it by ear,” Ussery says of his future. “I have been involved with HDNet since its launch, and Mark has a lot of other things going on. So that makes this job interesting. But I’ve never looked out and said, ‘In five years I want to do this.’ Opportunities have sort of found me, and I’ve been open to them. If Mark gets involved in other things and wants me to get involved in other things, great. If not, that’s okay, too. This job has been a lot of fun. It has been a wild ride.”