Hamman has reason to care, beyond a love of sports. The company he founded and heads, SCA Promotions, has a venture going in Germany that will pay consumers big—in refunds on purchases—if that country winds up winning the World Cup.

Crouched over the computer in his modest Dallas office, Hamman announces in his gravelly voice that Spain is now a “tiny” favorite—roughly 11 to 10 odds.

“We have a relatively modest stake. But if things go bad for our risk-takers it always comes back to haunt us, so we have to have our mind firmly rooting for Spain,” he says with a twinkle in his eye.

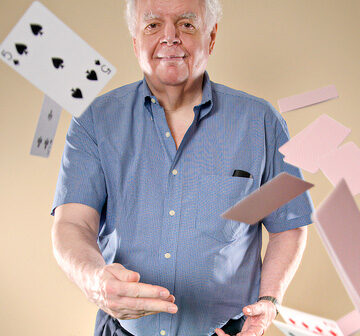

Meet the consummate gamesman.

By his own account, Hamman, 72, played his first game of poker at age 6 or 7. He dropped out of college because competitive bridge was more appealing, and played for money before entering the insurance business in 1966. He’s a 12-time world bridge champion and 50-time North American champion.

The business Hamman founded in 1986 is based on games and odds as well, which may account for the barely suppressed glee with which he talks about it.

Dallas-based SCA Promotions is a prize-indemnity insurer, better known as “the company that offers hole-in-one insurance” because of its roots in golf. But almost since its inception, SCA Promotions has been much more. It also bills itself as a designer and turnkey deliverer of prize promotions to its client customers, which range from Fortune 500 giants like McDonald’s and Allstate to Native American casinos.

“We live in an information-overload era,” Hamman says. “We have TiVo, where consumers avoid commercials. We have direct mail, but response rates are down. … For anybody selling any product, to get the attention of prospects is a brutal struggle.

“So, anything people can do to grab a piece of your mindshare will work to their advantage,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be related to the product; just something to get a little bit of attention.”

He’s talking about things like the Pirates of the Caribbean promotion that McDonald’s ran a few years ago; or PepsiCo’s $1 billion giveaway; or a “slot machine” that pays prize coupons to the winner at a casino—all of which were either insured through or designed by SCA.

Founded to take the risk away from businesses that wanted to give away big prizes but were faced with potential payoffs that exceeded their budgets or comfort levels, SCA calculates the odds on a prize giveaway or redemption and insures the client company against large-dollar wins for a fixed price. It will also design those promotions if the client wants.

Typically, a company like SCA will take a small portion of the risk and reinsure the rest of it. Chris Hamman, Bob’s son and SCA’s vice president, points out that the role of middleman in that game is more complex than it may seem.

For client-designed promotions, “we analyze the cases,” he says. “We get a lot of inquiries for promotions that are not in the format that any risk-taker concerned about their financial well-being would want to do. So we negotiate something that’s profitable.” Security—making sure a legitimate player wins the contest, and does so fairly—is a huge part of the function SCA takes on as well, he adds.

A Different Risk

The business SCA helped pioneer has grown during the past 24 years—partly as a result of the growth in professional sports, but also with the growth in marketing budgets and numerous variations on prizes and redemptions, those in the field say.

“The prize-indemnity world includes contests as simple as a hole-in-one to Internet competitions, coupon redemptions, lotteries, and hockey field competitions, to having plastic ducks float down the river and see if the ‘million-dollar-one’ wins,” says Martin Ridgers, a former exective with Entertainment Brokers International, a member of One Beacon Insurance Group.

The risk in prize indemnification, Bob Hamman points out, is of a different nature than that of traditional insurance companies, despite the million-dollar pots.

A property insurer, for instance, is typically hit with multiple claims from a disaster like Hurricane Katrina. A prize indemnification insurer takes the risk of paying off separate, unconnected events—however large the individual hit.

“Our risks have a wonderful property in that they’re one at a time, and they’re non-correlated,” Hamman says. “In fact, they may be better than non-correlated in that they’re mutually exclusive. We had a couple of promotions tied to the World Cup if either the U.S. or Mexico won. Germany, the U.S., and Mexico can’t all win; they’re mutually exclusive events.”

(Of course, Spain won this summer’s World Cup, beating the Netherlands 1-0 in the final game.)

Consistent Loser

Hamman got into the insurance business because his bridge winnings weren’t paying enough. In Los Angeles during the game’s big era in the late 1950s and early ’60s, young Hamman played in a variety of money games, including one held every Thursday night at the home of an insurance salesman.

“The total unvarnished truth is that … in this guy’s money game, I’d pretty much consistently lose and he was sort of worried I might starve to death,” Hamman says. “Though I was sort of rotund, so I didn’t seem to be in any immediate peril. He tried to recruit me into the insurance business.” By August 1966, Hamman says, “I had [just] three winning sessions, so I was fairly receptive at that point.”

Another man, John Everhart, got Hamman into the unusual side of the insurance business that is prize indemnification, he recalls. Everhart, the founder of the National Hole-In-One Association, an insurer of golf-course contests that pay off with prizes like new cars, was beginning to get requests to insure other types of events as well.

He asked Hamman whether he could take on that potential new business. “I allowed as how I could, and I did, and that got me started on this merry path,” he recalls.

Two years later the men parted company, and SCA was born.

A $30 million (annual revenue), closely held company with nearly 100 employees in Dallas, London, and Calgary, Canada, SCA has a niche in designing promotions for casinos. It counts about 175 casinos around the United States as its clients, a concentration that becomes evident as Hamman walks me around the company’s digs in the ClubCorp building off LBJ Freeway.

In one room are “slot machines” that dispense coupons for prizes. Here too are combination locks for Plexiglas containers of money and prizes; the contestant who can key in the correct combination wins the contents.

I envision complex proprietary software to compute the odds of this happening, but I’m wrong. “We do have some proprietary software, but it’s not really in the area of odds appraisal,” Hamman says. “This stuff has been around forever. It’s just that we do have a considerable amount of experience, so we’re pretty good at estimating.”

The proprietary software that Hamman referenced helps verify the security of games. “That’s an area where Bob has driven the ship,” Chris Hamman says of his father. Clients can be shown that the contests SCA manages are truly random, and “that’s huge,” Chris says. “Fraud is real.”

SCA often works with marketing or incentives companies that design redemptions and other promotions. TPG Rewards is one such client.

John Galinos, president of 15-year-old, Manhattan-based TPG, said his company specializes in creating incentives for packaged-goods giants like Procter & Gamble, Kellogg’s, and General Mills.

“One incentive we have, for instance, is movie cash—a coupon in a box of cereal that can be redeemed for a movie ticket,” Galinos says. “But the question is, how much? How many will be redeemed? It could be 8 percent, 10 percent, 15 percent. So companies like General Mills will buy redemption insurance.”

The first company TPG went to years ago for the insurance was SCA, Galinos says. “In the early days, there was no track record, so SCA standing in and taking the potential liability was very critical.”

SCA’s fixed fee ranges anywhere from 3 percent to 15 percent of the prize amount, depending on the odds and whether the contest is based on skill, behavior, or mathematics. And the company has paid off big, awarding more than $170 million during the past 20 years to its various clients.

Big Payoff

There was, for instance, a promotion for Fort Worth-based Dickies, the maker of clothing and boots for blue-collar workers and, more recently, fashion-forward followers of the look.

Dickies ran an “American Worker of the Year” contest for many years. In 2009, Dickies offered a chance at a $1 million prize if that winner, at the Dickies 500 Nascar event, could also choose the one out of 12 envelopes that held the name of the race-winning driver. Worker of the Year winner Michael McGee picked Kurt Busch and won the $1 million. Dickies, backed by SCA and its reinsurers, paid off.

One contest SCA didn’t want to pay off was an insured $5 million bonus if famed cyclist Lance Armstrong won a sixth Tour de France crown, which he did. After accusations of doping surfaced in a book by a British journalist, SCA wanted to investigate. Armstrong sued. SCA lost a court challenge on the arbitration and later settled for about $7.5 million, including costs.

The company’s name has come up again as new doping allegations—still steadfastly denied by Armstrong—have surfaced, along with a federal investigation.

Hamman doesn’t want to talk about it, saying only: “We’re watching with extreme interest.”

It’s probably impossible to separate Hamman the business success from Hamman the extraordinary bridge player, whose prowess at the game is reknowned in the tight circle that is championship, competitive bridge.

Jeff Tillotson, the attorney who represented SCA in the Armstrong arbitration, tells this story:

“I’ve never played bridge, despite Bob’s efforts. I was on a holiday with my wife, a cruise. They had bridge lessons and asked us to join,” Tillotson recalls.

“I declined, but said, ‘I have a friend who plays—a guy named Bob Hamman.’ It was like telling a group of girls in the ’60s that I knew Paul McCartney,” he says. “Bob is a rock star in that world.”

Indeed, he’s so much a rock star that SCA’s chief operating officer, Hemant Lall, ultimately joined the company through a bridge connection. “I first read about Bob when I was 16 years old, going to college in India, and I read about the Dallas Aces,” Lall says. The Aces were a professional team formed by the late Ira Corn to win world bridge championships.

“I got accepted at places like Stanford, but I came to … [Southern Methodist University] because it was in Dallas, and I wanted to be near the Dallas Aces,” Lall says. He never became part of the Aces, but Lall himself has won five national championships—all, he said, while partnering either with Bob Hamman or his wife, Petra Hamman.

Lall joined SCA in 2003. “Bob is brilliant in coming up with new products, new ideas for promotions. I have zero knack for that. I’m more involved with managing the business,” Lall says.

Hamman’s bridge acumen carries over into the business in this way, Lall says: “Bob’s biggest strength in bridge is that whenever a disaster occurs—and disasters occur about every seven minutes in bridge—he can forget about it and move on to the next hand, play it on its own merit.

“In the type of business we’re in, you sometimes have to pay out $1 million,” Lall says. “And you have to make the next decision on its own merit, not on what just happened.”

Hamman’s own description of the game and its attraction for him betray the competitiveness and gamesmanship that seem at the heart of the man.

“It’s a very, very good game. It’s a complex, challenging game, and the people who play it, like it,” he says. “It doesn’t really cater to the gardening crowd. Basically it caters to really competitive individuals who want to win.”

Bridge is still a big part of Hamman’s life. He and Petra—they met at a bridge tournament—spent much of this past Fourth of July weekend at a regional tournament in Austin. Later Bob traveled to a U.S. national competition in New Orleans; then he was in Council Bluffs, Iowa, playing in a regional tournament attended by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates. Around Labor Day there was a regional closer to home, in Richardson.

Has bridge helped Hamman’s business career? “It has helped me with some number of contacts,” he says. “I have very high visibility in the bridge community. Let’s say it hasn’t hurt.”

He warms to the subject: “Bridge is a particularly good teacher, because one of the big, big problems in the business world is that as the world gets more complex, you have to make decisions based on partial information, and in a very timely manner.

“We all know the maxim that it’s better to be safe than sorry,” he says. “But sometimes the right decision too late is no better than the wrong decision. So, at least in my view, it’s very useful to work on skills that enable you to make decisions based on fragmentary information.”

Does he have any other enthusiasms? “Well,” he says, “I like to play backgammon.”

The gamesman, who says he’s not thinking of retiring—“Ha! The point is, [work is] a lot of fun!”—typically watches three football games at once on fall afternoons, surrounded by three television sets at home.

“Other sports, I watch them all,” Hamman adds. “Tennis is a good sport, because the action is fast, it’s continuous, and it’s one person playing head-on against another. Whereas in golf, you can’t make your opponent play worse, so it leaves something to be desired.

“My bias is big time on interactive games. For a competition to be called a sport, it must be interactive,” he concludes. “A head-butting competition. Not seeing who can solve the Sudoku puzzle faster.”