I received an invitation from Dr. Kern Wildenthal to come back to Dallas to organize the infrastructure required to mount a campaign to build a world-class performing arts center in the Dallas Arts District. Being a native Dallasite, and one who valued culture, I was intrigued with the project because of its historic significance. So in 2000 we moved back to Dallas and went about the process of organizing the structure to build the campaign.

The success of that project is directly attributable to the common denominator of all successful projects like this: the volunteers. At the very beginning, we recruited 26 intrepid volunteers to be the founding board of directors for the center. Some of these people were passionate about opera, some were passionate about theater, all were passionate about Dallas. And they all had the financial capacity to make a generous gift to help build the center—or they had access to wealth.

So we charted an ambitious nine-year course to engage internationally renowned architects, to raise 90-plus percent of the money in the private sector, to contain campaign expenses to less than a nickel of each dollar, and to build a “new Lincoln Center” in downtown Dallas.

Did you personally pick the core group?

I handpicked the founding board, based on the criteria I thought were essential to our success—balance being one of the primary ones. And then, over the last nine years, we augmented the board to keep it fresh, to bring in younger people and other people. Only one person resigned—and that was planned—and then we had three deaths on the board in the last nine years. Otherwise the founding board is still with us today. We went from 26 founding directors to about 63 on the board today. Because, with a campaign of this breadth and length, we needed a board to keep everybody energized and excited—to not let the fatigue of the exercise begin to show itself.

Did you oversee the entire effort?

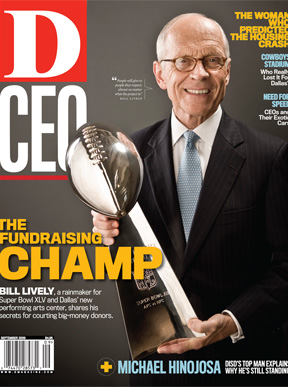

I was the president and CEO, but I was one among many. My whole philosophy about this project—and SMU and the Super Bowl—is that you’ve got to engage the right kinds of people. When they write the book about the performing arts center and that great campaign, there’ll be chapters dedicated to the volunteers who kept their promises. When I left in December, that board I reported to had given $160 million of the money that we’d raised by that time.

What do you mean when you say some of the board members had “access to wealth”?

They were people who couldn’t make a million-dollar gift themselves, but their stature in the community—what they’ve done for Dallas in different ways—opened doors for them to go with me to ask for gifts of that size. There were directors who helped shuttle me around the corridors of City Hall, for example. I didn’t know anything about City Hall—I hadn’t needed to, at SMU.

Can you describe how a typical pitch meeting for the arts center would go?

We would have private confidential meetings with the volunteers to identify their friends and neighbors, and sometimes even their relatives, who might have an interest in this project for cultural, civic or economic purposes. The next job was to identify the team that would go meet with that donor candidate to make our case. Oftentimes we’d take two or three directors with me, and we would go sit down with the family—in their home most commonly—and we would talk about this center from one of several perspectives: its lasting impact on our cultural landscape; its longstanding economic impact on the region and the city; or other ways the center’s going to be important. Most of the time the volunteers who went with me had already done it—had already made their gifts. What they were doing in effect was saying, “Follow me.”

The message had to be tailored differently each time, I would imagine.

Yes. It may be the same project—like the performing arts center—but each time you make a request of a donor candidate, it’s different. You customize the request. You may have the same “ask” team, but you customize the request to be appropriate to that person to that organization at that time. And every one of these has to be very thoughtfully considered.

Did you have a pretty good batting average with these request meetings?

I was asked that question by The New York Times, and I think I said it was something like .700. But we studied the pitchers very carefully. We didn’t have many at-bats. We didn’t go in to request gifts very often if we didn’t have a good sense that the donor candidate might become a donor. We knew the family, or thought we did, or the individual or the company, and we took a fine team with us and oftentimes we hit a home run.

Based on your experience, what’s the key thing people who raise money need to keep in mind?

The single most important thing in any high-dollar fundraising initiative is the volunteer unit. There’s nothing more important. The project itself can be incredibly noble and worthy, but if you don’t have volunteers who are people of integrity, who commit their time and resources in a very structured way, you very likely will not achieve your objectives.

I’ve given many seminars around the country in the last several years to the CEOs of nonprofit corporations. Invariably, you encounter two elements in these discussions. The first is the spirit of entitlement: “We are noble, we deserve, they should give.” Well, the spirit of entitlement in my judgment is almost every time inappropriate.

Secondly, you find many times that these organizations have boards that are filled with wonderful, calm, gracious, good people who care deeply about the mission of the organization, but they don’t have the financial capacity to elevate the institution to a new level. So, you’ve got the wrong people in effect involved in the life of the institution at a time that it needs to grow and develop. So what you have to do in that case is not alienate those people, but appoint other people to roles of responsibility so that you can take that institution to the next level. That’s complicated. There’s no shortcut.

I don’t particularly like the label fundraiser; I like the label “strategist.” I think my jobs require me to be organized and strategic, and then I have to be a recruiter, and recruiting means that I have to convince extraordinary people of the quality of the project I’m involved in. If I can, then they’ll become the disciples. They’re the ones that carry the banner, and I become their choreographer. But fundraising as we’re talking about it in this interview is an art, not a science. It’s not something that requires a bureaucracy, or that can only be done one way. And the common denominator for success, as I said, is the volunteers.

On the other side of the equation, what motivates people to donate large amounts of money?

I think that in this era of accountability, people give money to people. The project must be noble, there must be accountability, and transparency, there must be some way to quantify the impact of the project. But people will give to people they respect, almost no matter what the project is—whether it’s humanitarian or religious or cultural, whatever it is.

And if you believe that, and I do, then you involve distinguished people with integrity in the enterprise, and those kinds of people can command the attention of like kinds of people. And so invariably at SMU and with the performing arts center and even with the Super Bowl, you’re taking very noble people to ask other noble people to make a gift or commit a sponsorship. The integrity of the people you’re with carries the day, and people respond to that.

About 80 percent of the million-dollar donors to the campaign to build the performing arts center had never given [as significantly] to the arts before. They gave the gifts that they did for two reasons: They valued their gift as an investment in the future of Dallas, and they also valued the person that asked for the gift—a friend or a colleague or a respected leader in Dallas like a Caren Prothro, or a Deedie Rose, or a Howard Hallam, someone like that.

If you don’t get those kinds of people involved, you cannot raise the kinds of dollars that extraordinary projects require for their success. There’s just no way you can do it.

Does the donor’s ego come into play?

I suspect ego does play a role in this but, more importantly, I learned a long time ago that staff people like me cannot command the attention of important leaders and people of extraordinary means. You need other leaders and people of means to command their attention. So I am what I call a “posturer.” I help posture people with extraordinary ability and the means to ask other kinds of people to make gifts or sponsorships that we need.

Do tax breaks play a role?

Sure. With the performing arts center, there are people who I’m sure gave the gifts they committed for the tax deduction. But I suspect the great majority of the donors gave because they valued the project.

How important is it for nonprofits to control their spending, especially in tough times?

The label nonprofit is not a license to be inefficient. A nonprofit company ought to work as efficiently as a for-profit company. There’s no justification for doing otherwise. I think donors are going to demand accountability and transparency, and they should.

With the performing arts center, our goal was to be able to tell donors at the end of the campaign that only 5 cents of every donor dollar was used to run the campaign. Now, the national average is much [higher] than that. And, when I left the center in December, the average cost was about 3 and one-half cents on each dollar, which is unprecedented.

That seems extremely low.

We had a great advantage at the performing arts center, though. We began that campaign in the fall of 2000 with no baggage. We had no bureaucracy; we had no organization whatsoever. No bad habits, no good habits, no habits at all. So, we could design a business plan to operate an eight- or nine-year campaign without the encumbrances that pre-existing institutions—a university, a symphony, a library—already have. When they have a capital campaign, they have systems in place that they have to address; we didn’t have those.

Same thing with the Super Bowl. We didn’t have any organization, we didn’t have any staff, we didn’t have any money, we didn’t have anything. So we began this the same way, with no bad habits and no bureaucratic tendencies. Now we can be very thrifty, very cost-effective, very transparent—and we need to, because we’re the stewards of other people’s money.

Summing things up, what would your advice be to nonprofits and other fundraisers in this challenging time?

Whenever I speak to nonprofits lately, my theme is this: When the recovery begins—and it will begin—you’d better have four things in place to be ready for it.

No. 1, you need to have a strategic plan that defines how you’re going to run this organization thoughtfully and practically and in a business sense for the next couple of years. No. 2, you need to have extraordinary volunteers that command the attention of other leaders supporting the initiative. No. 3, you need to have a staff in place that is cost-effective and efficient—not bureaucratic with levels and filters and people you don’t need that you can’t defend. And No. 4, you need to have a communication strategy that conveys all these things in a timely and consistent way to these people. If you do that, you’ll be fine.

You’ll do fine because competition is good, and the organization that makes the most compelling message will carry the day. The ones that depend on the spirit of entitlement will fail, and probably should fail. It’s a new world, and if you don’t have accountability and efficiency, you can’t defend your position. And that’s going to be critical as we go forward.