Changing The System

Former Dallas mayor and nominated (at press time) U.S. Trade Rep. Ron Kirk never went hungry growing up, Kirk told me a while ago.

Still, I’m sure it wasn’t easy being one of four children, living on the wages of his mother, Willie Mae (who was a schoolteacher), and his father, Lee (a post office clerk).

Kirk’s father wanted to be a doctor, but in the segregated South, that wasn’t going to happen.

Back in a previous life, when I was interviewing him for the Dallas Business Journal, Kirk told me that the racially oppressive climate only motivated him and his parents to overcome the system.

Lee and Willie Mae Kirk were active in the NAACP. Ron Kirk, meanwhile, wasn’t sure what he would do. He only knew that he wanted to change the system, and that law was one way to do it.

“When someone asked me what I wanted to be, I at least marginally knew, and had heard of Thurgood Marshall and the others,” he told me.

His biggest challenge, he went on, was that he didn’t know how to get from wanting to be a lawyer to becoming one.

No one in his family had done such a thing.

His parents paid for his college—as they did for all their children—on their meager salaries. They were determined that their children all would attend universities—something that racism had kept Kirk’s parents from doing.

Kirk attended The University of Texas law school, with the intention of becoming a high-powered trial lawyer. Kirk had set about doing that, working at a Dallas law firm, when he got a surprise call from Washington.

It was longtime statesman U.S. Sen. Lloyd Bentsen: He wanted Kirk, who had clerked in the Texas Capitol building, to work on his staff in Washington.

Kirk thought he would serve a short stint, then go back to private practice when he was done.

But Kirk has proven to be the Michael Corleone of Texas and national politics: Just as he thinks he’s out, they keep pulling him back in.

He served as Texas’ secretary of state, then two terms as Dallas mayor.

He doubted aloud whether he would ever return to public service in our interview, though the Obama campaign was picking up momentum as we spoke. Kirk was likely bundling major campaign contributions for Barack Obama even then.

Now that Kirk’s on the national stage, it’s hard to say where Obama’s coattails might lead him.

TRISHA WILSON

Perseverance Pays Off

International architectural designer Trisha Wilson had hoped to get into design after she graduated from The University of Texas in 1969. After all, she earned a degree in interior design. But Wilson knew she had to start somewhere: That’s what led her to the door of Titche-Goettinger, a now-defunct Dallas department store. She hoped she would at least get a gig as a window dresser.

But even that opportunity wasn’t open.

She ended up selling mattresses. She made about $4,000 her first year.

“Back then, I only had three [good]outfits,” Wilson says, adding that she would rotate the outfits.

Wilson said she at first lived with four of her friends in a single apartment—but they never felt poor or disadvantaged.

“I don’t ever remember having to do without anything,” she says, conceding that eventually, she had to move back home to save money.

Wilson says that money was never a motivating factor toward success. She says her upbringing in a dysfunctional family, where her mother and father divorced when she was 15, actually drove her to succeed. When her father died, she qualified for social security to pay for her tuition, she recalls.

“I think I was just a survivor,” Wilson says. She said she knew she had to succeed, because she didn’t have anything to fall back on.

Wilson’s perseverance paid off: she got an internship with Dallas architect Harry Hoover, designing (of all things) stained-glass windows. Eventually, her work led to designing the first Chili’s and Kitty Hawk restaurants.

She says that at the time, succeeding as a woman was extremely difficult.

Given all the obstacles she faced back then, Wilson says there’s no reason people can’t succeed in business today.

“You have no reason not to make it,” she says.

A Cabin Without Plumbing

Both Sam Wyly and Ross Perot bled IBM blue, when it came right down to it.

But when they saw the company wasn’t taking advantage of market conditions, they took off in different directions to pursue their fortunes.

In Wyly’s case, in the early 1960s, he took $1,000 and parlayed it into the $600,000 he needed to form University Computing Co., which used transistorized computers to perform computations for scientific and engineering ends for other companies (including Sun Oil and Texas Instruments). University Computing went public in 1965 and, within four years, shareholders had a 100-1 return on their holdings.

“Not bad for a too-small noseguard from Delhi (Louisiana) High School,” Wyly writes in his book 1,000 Dollars and an Idea.

From there, Wyly co-founded Earth Resources Co. (an oil-refining and silver-mining operation), bought and expanded the Bonanza Steakhouse chain, purchased and expanded the Michaels craft chain, and founded Green Mountain Energy.

Yet it would be harder to find a more true-to-life slumdog millionaire in Dallas.

Though both his mother and father came from relatively wealthy families, Wyly’s parents Charles and Flora Wyly found themselves pretty much wiped out by the Great Depression (like nearly everyone else).

Sam and his brother, Charles, and their parents lived in an unpainted wooden cabin without plumbing on a Louisiana cotton plantation. They had all but given up the notion of trying to survive on the cotton crops, which Sam’s father was supposed to be managing.

They scraped enough money together to buy a newspaper (his father aspired to be a journalist at a major newspaper), a Western Union franchise, and a small insurance agency. Sam’s experience with the Delhi Dispatch had him considering a career in journalism … until an IBM salesman showed up in his father’s office to sell him a typewriter.

“The man was well-dressed, in a smart suit with a white shirt and a dark tie; he spoke intelligently and I remember he drove a brand-new Cadillac,” Wyly wrote. “I sat there looking at him, thinking to myself how impressive he was and how he projected success.”

The die was cast.

Remembering The Rabbits

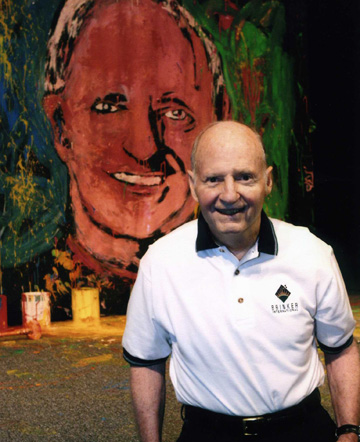

Rapidly multiplying rabbits haunted Norman Brinker, even when he was lost in a coma.

“Gosh! What am I going to do about those darned rabbits,” Brinker was heard muttering while on the fringes of a coma in 1993.

Brinker’s mutterings weren’t the product of a complete delusion. The restaurant entrepreneur suffered an intense trauma from a polo accident, and his subconscious was still trying to wrestle with a demand-supply quandary he’d faced when he was about 10.

In a bid to earn enough money to feed his horse, Silver, young Norman bought 13 rabbits for breeding. Soon, those animals multiplied to 150. They were literally eating their way out of captivity.

That forced him to hold an emergency clearance sale.

More than 50 years later, “Norman treated it as a learning experience,” Brinker and Donald T. Phillips write in On the Brink: The Life and Leadership of Norman Brinker. “Begin with the end in mind; sales must equal production; and know how you’re going to get out before you get in.”

Brinker’s drive to obtain and keep a horse led him through many entrepreneurial adventures.

Brinker grew up poor and began working not long after he was old enough to count. First, he picked cotton. When he realized he could make the money easier, he cut grass. After surviving the rabbit debacle, he tried breeding and selling both cocker spaniels and horses (the latter more successfully). By age 14 in 1945, Brinker had saved up $1,300 (in today’s dollars, that would be more than $15,000).

Brinker still keeps a picture of himself and one of his rabbits as a reminder, among his memories of what led him to either create or lead Steak & Shake, Bennigan’s, Burger King, Cozymel’s, Macaroni Grill, and Chili’s.