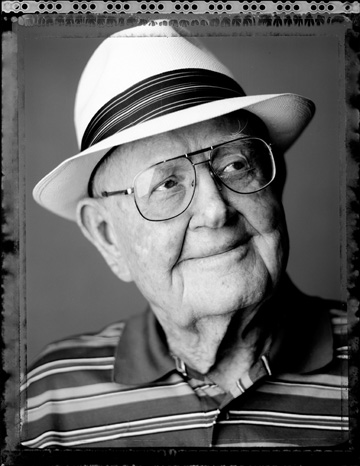

Through luck, talent, hard work, and risk-taking, Dallas CEO Patrick McEvoy Jr. has built his Carrollton-based Western Extrusions Corp. into the largest privately held aluminum-extrusion manufacturer in the United States, with annual sales of a quarter billion dollars.

Not that his business success was any help to him when he reported for work early one May morning in the cart barn at the TPC Four Seasons Resort in Irving. Starting at 4 a.m., McEvoy and three other members of Dallas’ Salesmanship Club took turns tinkering with dozens of electric golf carts to get them ready for a new round of their annual PGA Tour event, the HP Byron Nelson Championship.

While McEvoy is a captain of his own corporate ship and a leader in his industry, when he puts on the bright-red Salesmanship Club pants he’s just another week-long worker bee, helping to raise more than $6 million annually for charity. Water had be to added to each golf-cart battery and if, heaven forbid, some volunteer or official had failed to return a cart the evening before, it was up to McEvoy and his crew to trudge through the North Texas dark to track the missing vehicle down.

“It was a tough job,” he says. “I certainly wasn’t using my college degree that week.”

It all made McEvoy one of the highest-paid cart jockeys in Salesmanship Club history—excepting possibly the other execs who labored with him, and the dozens more who have preceded and succeeded him in that blue-collar task.

That, in a nutshell, is the genius and uniqueness of the 89-year-old Salesmanship Club of Dallas, which has raised more than $100 million for its locally based Youth and Family Centers via its annual PGA Tour tournament, which began in 1968. The figure makes the Salesmanship Club tourney the most successful professional charity golf event in the U.S or anywhere else in the world.

There are currently 620 members in the club, with an average of 16 new members accepted each year. They pay annual dues of $600, plus attend and pay for a weekly Thursday lunch. They also wear the club’s trademark red pants, which members have sported at their PGA Tour event since the tourney’s early days.

Salesmanship Club members are responsible for selling millions of dollars of tickets and sponsorships to the annual HP Byron Nelson Championship—to be held May 21-24 this year at the TPC Four Seasons Resort in Irving—and then putting in hundreds of hours running the tournament, overseeing everything from the cart barn and trash pickup to the marshalling and crowd control.

It’s millionaires doing the mundane; CEOs mixing manual labor with mutual friendship for a cause they hold dearer than any lofty board or grandiose civic achievement. “We’re a bunch of Indian chiefs willing to be Indians to give something back to the community,” summed up recently deceased long-time member Lloyd Gilmore.

From McEvoy and Container Store CEO Kip Tindell, to deceased legends like car dealer Rodger Meier, lawyer Woodall Rodgers, and civic leader Julius Schepps, the North Texas business executives continue to put in hundreds of hours each year in sweat equity for their vital cause.

It didn’t take famed Dallas orthopedic surgeon Dr. Richard Schubert, who has performed hundreds of hip and knee surgeries, long to find this out. In his second year in the club, he was called upon to perform a slightly different kind of operation.

“We had some really heavy rains before the tournament started, so we went over to (tournament second course) Cottonwood Valley, to clean out the drains and dredge out the creek beds near the course,” Schubert recalls.

“We were in water up to our ankles. There were snakes everywhere, and I thought this is definitely something they didn’t teach me in medical school. I could have probably helped with any snake bites, but the reason we were there was to make the course and the creek look good for the fans and TV.”

These executives are fiercely loyal to their duty of shared sacrifice, and just as disdainful of any newcomer who wants to treat membership in the Salesmanship Club as another check mark off the corporate do-gooder list.

“I always chuckle when I meet some new CEO whose corporate PR team has given him a list of things he has to do to be accepted as a new business leader in Dallas,” says Dallas PR firm owner Andy Stern, a member of the club since 1985. “He has to join the right civic organization, get in the correct country club and, lastly, join the Salesmanship Club.”

Stern met just such an indi–vidual a few years ago, when a new CEO arrived at the club’s weekly Thursday noon meeting. After a half-hour of corporate fellowship and listening to NBA commissioner David Stern speak, the visitor leaned over to Stern and gushed, “This is great. I’m really enjoying this. How often to you do this?”

Without a smile or a second thought, Stern shot back, “Every Thursday for the rest of your life.”

The grin quickly faded from the corporate visitor’s face, and he was not seen making many more visits to the club.

“The Salesmanship Club is not for everyone,” says Dallas lawyer Mike Massad Jr. “It’s a great time commitment. You have to check your ego at the door, give up any title or kingdom, and get into the work to make it happen.”

Adds Larry Haynes, a partner with Ernst and Young in Dallas: We “never say ‘no’ to any assignment. At the club, everybody else is doing their part; you want to as well.”

Tournament jobs are rotated every two to three years, meaning that just when you’ve mastered the art of pouring battery water into electric carts, it’s time to move on to marshalling a crosswalk, working the noisy pavilion, or being the human answer man for thousands of North Texas golf fans.

“It’s really purpose-driven fellowship,” says Tindell, who’s served as a hole marshal on No. 14 at the TPC Four Seasons for the last couple of years.

After his three-year stint in the cart barn, McEvoy spent three years in tournament administration, culminating as general tournament chairman in 2000. But, unlike some chairmen or presidents who retire to the lecture circuit or a vacation home, he was shuttled back down the assignment ladder at the club. Now he’s back to marshalling a hole—the job he started with in 1985.

Excuses of work, travel, and busy schedules are not accepted lightly, if at all.

Just ask Dallas’ Paul Bass Jr., Southwestern Medical Center Foundation chairman emeritus and private money manager, about work-related excuses and the Salesmanship Club.

Bass had only been in the club a few years when his employer transferred him from Dallas to Houston. Intent on staying associated with the club, Bass approached the member who had sponsored him for membership and asked if there was some type of inactive status while he was living out of town.

The response may have surprised him, but was well within the Salesmanship Club “no excuses” mantra. “You’re only going to Houston; you can still come back for the Thursday meeting,” he was told.

Which is exactly what Bass did for three years before moving back to Dallas full time.

Since 1920, when the club was founded by civic leaders such as James K. Wilson, Sol Dreyfuss, Conrad Hilton, and Woodall Rodgers, its first president, members have willingly shouldered the task of raising money for local boys and girls who need help to better their circumstances.

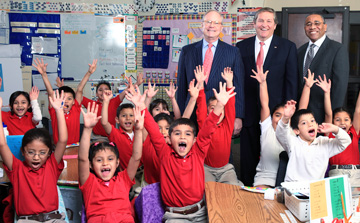

The club operates the J. Erik Jonsson Community School in Oak Cliff, as well as the newly opened Family Works Center on Harry Hines Boulevard in Dallas. It also maintains a non-residential camp in East Texas, which is used for a variety of therapeutic and recreational school and family purposes.

The club services more than 7,800 kids and their families each year with a budget of about $9 million, provided by the golf tournament proceeds and other club projects.

“We’re not raising money for charity; we’re raising money for our charity,” says 2008-2009 club president Frank Swingle. “That’s a huge difference.”

The club first organized Golden Gloves boxing matches in the 1930s and ’40s, then helped run the 1963 PGA Championship at Dallas Athletic Club, its first golf venture. Until 1989, it also spent more than 30 years sponsoring each season’s first Dallas Cowboys pre-season football game.

The group’s first official PGA Tour tournament began in 1968, with namesake and professional golf icon Byron Nelson. After retiring from pro golf in the late 1940s, Nelson, a native North Texan, settled down at his beloved ranch in Roanoke, never to live anywhere else again.

The alliance between the club, with its hard-working group of Dallas business leaders, and the local living golf legend turned out to be the most successful professional golf partnership of all time.

For more than three decades, they raised nearly 10 percent of all charity dollars given on the PGA Tour and, in 2007, were honored as the first golf tournament organization ever to raise $100 million for charity.

“When I’m getting ready to go out and sell $100,000 worth of golf tickets, sometimes the thought will come, ‘I could be doing something else,’ ” says McEvoy of the Western Extrusions company. “But then I think about the kid whose life we’re changing, and the needs we’re meeting.”

The combination of Nelson and the Salesmanship Club brought record sales and heady days through much of the 1980s and ’90s. While Tiger Woods turned down President Bill Clinton’s request to join him at a civil rights ceremony a month after winning his first Masters Golf Tournament, he accepted Nelson’s invitation to make the Dallas tournament his first since his record-breaking win.

Woods’ appearance launched a string of record crowds, big-name winners, and millions of dollars made for the local charity.

Tough Times

However, dark clouds began to form over the club and its tournament by the middle of the opening decade of the 21st century.

First, the PGA Tour, which had greatly benefited from the Salesmanship Club’s lead in charity giving, decided to take—some locals prefer the word “steal”—the club’s prime tourney date in mid-May. With the Tour’s own tournament, the Players Championship, awarded the traditional mid-May Nelson date, the North Texas event was booted back to less desirable late-April dates in 2007 and 2008.

Then, Nelson passed away in late 2006 at age 94, removing the motivation or obligation many of the top professional golfers, including Woods, had to play in the local tournament each year.

Finally, the course at the TPC Four Seasons Resort had become worn out after two decades of use and had to be renovated without skipping a tournament year.

Those were “some of the toughest days I’ve seen,” admits 2009 tournament chairman Charley Spradley. “We’ve crested some tough hills before. We had some real peaks before when Tiger came in the mid ’90s, but the last few years, the valleys were a major challenge.”

But with their typical long hours, work ethic, and well-honed business acumen, club members came together to restore the golfing institution’s luster.

They teamed with title sponsor EDS and Ron Rittenmeyer, then its tough-talking chairman, to negotiate with the Tour to return to May on the golfing calendar, linking up with the Colonial, Fort Worth’s PGA Tour event, once again.

They worked with Four Seasons Resort owner BentleyForbes, the PGA Tour, and local golf architect D.A. Weibring on a multimillion-dollar project to fashion a greatly renovated golf course—a renovation that’s now drawn rave reviews from Tour players as well as hotel guests who play the course the other 51 weeks of the year.

As a result of all this, “I think we’re really well-positioned for 2009 and beyond,” says Doug Hawthorne, the CEO of Arlington-based Texas Health Resources. “When the tough decision needs to be made, the members really come together with the same principles which help at their work helping at the club. The reason this is so special is that there is nobody to delegate it; you just do it.”

Even in a tough economy, the sales goal of $12.5 million for 2009 hasn’t been reduced—because it can’t be. The needs of the charity remain. “I’ve had businesspeople tell me they can reduce expenses all they want, but the two things they still have to buy are Cowboys tickets, because their big customers want them, and Byron Nelson tickets, because of what we do for charity,” one member says. “That makes you feel good, that people recognize our work.”

To perform its annual good deeds each spring, the Salesmanship Club has found two strong allies in the city of Irving and the TPC Four Seasons Resort.

“This is a city which is identified with business and attuned to the speed of business,” says Maura Gast, executive director of the Irving Convention and Visitors Bureau.

“You have the leading CEOs of the area coming together for a common cause,” she says. “It’s not their day-in, day-out job, but the true test of leadership is how to follow, and you can’t tell the difference here between titles and positions.

Four Seasons General Manager Michael Newcombe agrees. “The CEOs who join the Salesmanship Club or conduct meetings in our conference center are some of the same you’ll see at the Byron Nelson Championship,” Newcombe says. “Roping and staking the course, shuttling pros to the practice range, selling merchandise; they are willing to do it all. To me that defines a true CEO.

“I think it’s understood the Four Seasons and the Salesmanship Club speak the same business language,” he adds.

Perhaps the best credo for the dirty work done well came from legendary car dealer Meier. Meier spent many a tournament pulling cars out of the Preston Trail course-side parking lot, which annually turned to mud at the former tournament location due to frequent spring storms.

“You couldn’t pay me to do this job,” Meier once said, “and you couldn’t pay me enough if you did.”

When it came time to leave the dreaded muddy lot and move to their new location in Irving in the early 1980s, with acres of paved parking, Salesmanship Club members turned around and sold the field adjacent to Preston Trail to a developer for millions of dollars.

Then they donated the money to the local cause they hold so dear.