|

| illustration by Harry Campbell |

|

In Dallas, a town where oil and gas barons are spoken of almost reverently, it may be hard at first blush to imagine anyone doing much for the environment.

Highway intersections with names like the Mixmaster and the High Five are jammed with single-occupancy vehicles. The air is so dirty, the Environmental Protection Agency has declared Dallas, Collin, and Tarrant counties to be in a so-called non-attainment zone for ozone standards. And according to Green Dallas, a city environmental initiative, commercial buildings are responsible for as much as 30 percent of the greenhouse-gas emissions that pollute Dallas’ air.

To address the dirty-air problem, city leaders have decided on a unique tack: taking direct aim at new building. This time next year, all new construction in Dallas—that’s commercial and re–sidential construction—will be required to meet tough new standards the city has implemented in an effort to become the “greenest city in the U.S.” by 2030.

By OK’ing a green-building ordinance, Dallas is attempting to shed its traditional image of conspicuous consumption, and to rebrand itself as environmentally friendly. At the same time this transformation may seem excessively ambitious, because relatively few city resources have been allocated to support the green transition so far. There’s no doubt, though, that the business and especially the building communities will find themselves burdened with more up-front costs and more red tape than they would have, absent the new law.

So, how did all this come about?

|

| CHANGE AGENT: Zaida Basora, a city building official, has played a key role in Dallas’ environmental evolution. photography by Adam Fish |

Behind the scenes, the green movement in Dallas has been gathering steam over the last several years, with the most dramatic changes coming in the last eight months. Earlier this decade, the city began quietly organizing task forces to see where it could make “green” improvements at a municipal level, largely by following the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, or LEED, standards.

LEED works like a big checklist, with six areas—sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, indoor environmental quality, and innovation and design process—that have their own sets of possible credits. For a building to be “certified” by LEED—the easiest level to attain—it must attain between 26 and 32 points on this checklist; 33 to 38 points qualifies it for silver status; 39 to 51 points mean gold; and 52 to 69 points will bring platinum status.

In March 2003, the Jack Evans Police Headquarters became the first municipal building in town to get a LEED silver designation. Around the same time, the city adopted a program requiring all municipal structures of more than 10,000 square feet to meet LEED silver standards. Since then, the city has opened five buildings that reach LEED silver or higher.

“We couldn’t very well ask the private sector to develop green buildings unless we did it ourselves, could we?” City Manager Mary Suhm said shortly after the police headquarters was completed.

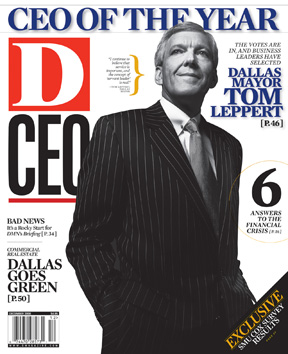

Green plans for the private sector became a top priority shortly after Tom Leppert, a member of the CEO Advisory Council of the U.S. Green Building Council, was elected Dallas mayor in June 2007. A few months after Leppert’s election, the City Council approved a green-building resolution that led to an ordinance enforcing construction standards.

“We’ve passed a policy that says Dallas is going to be an all-green city,” Leppert told a reporter last year. “We’re not necessarily known for being green-friendly. This, in one fell swoop, alters that.”

The new mayor and the City Council began thinking big in environmental terms, aiming to be “carbon neutral” by 2030 by cutting the city’s building energy use in half, retrofitting existing buildings, and using renewable fuels.

|

| LOFTY GOALS: Kirk Johnson, a LEED-accredited project manager with Corgan Associates, says green building is becoming a way of life in the architecture business. photography by Adam Fish |

“The city of Dallas adopted green-building resolutions for municipal buildings in 2003. We’ve had five years of experience doing this, and we started thinking about [enforcing green regulations] citywide last year,” says Zaida Basora, a building official with the city of Dallas Building Inspection Department. Last spring, “we contacted industry partners [and] members of the building community locally to start kicking around ideas for what to bring to the green-building program.”

Basora, a founding member of the U.S. Green Building Council’s North Texas chapter, is also a member of the local branch of the American Institute of Architects, and was one of the first people in Dallas-Fort Worth to attain the LEED accredited professional designation. She’s been involved in the green-building movement since 2001, and says it was “sort of by default” that she became the leader of the green-building task force.

“When Leppert got elected last summer, he kind of revamped the whole thing,” Basora says. “He was the catalyst to look at this seriously and come up with a real program that could be implemented.”

The Dallas City Council unanimously approved the tough new building rules this past April, stipulating that as of Oct.1, 2009, major changes would be implemented in construction guidelines within Dallas’ city limits.

One of the most notable elements of the new Dallas rules is that, in contrast to green-building ordinances in Boston, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., Dallas’ law incorporates green standards for all levels of residential as well as commercial construction. New homes in Dallas, for example, will be required to meet energy conservation standards and to use water-reduction tools like low-flow toilets and showerheads.

For the business community, the biggest changes relate to new construction of 50,000 square feet or more. Under the ordinance, those buildings will be required to fulfill about 85 percent of the minimum qualifications necessary to receive the LEED-certified designation. Specifically, businesses will be required to attain 22 of the 69 points outlined by LEED’s New Construction version 2.2. Of those 22 points, at least one point must go to a 20 percent reduction in water use, and at least two points must fall under the credit for improved energy performance.

Meantime, all new commercial buildings smaller than 50,000 square feet will have to be 15 percent greener than the 2006 energy code standards, have fixtures that use 20 percent less water than the EPA’s 1992 standards, and include outdoor lighting restrictions.

In addition, owners of all new commercial con–struction—regardless of size—must agree to let utility companies release the building’s annual consumption data to the city. “The release of information is so that we can understand … energy consumption … by district or sector,” Basora says. “Right now we’re able to get [it] overall, but we’re not able to break [it] down. It’s not meant to penalize anybody; it’s meant to identify what we need to do to reach our target.”

Basora says the utility information will not be released to the general public.

DALLAS VS. OTHER CITIES

While passing an ordinance like this so quickly—and enforcing it beginning the following year—is not without risk, it makes sense in some ways, given Dallas’ location and environmental situation.

North Texas is the fourth-largest region in the country, and was the country’s fastest-growing region in 2007. The local population is projected to reach 9.1 million by 2030, and 12 million by 2050. To prepare for such growth, local governments are desperately trying to change the way their cities operate.

During a sustainability conference at The University of Texas at Arlington in October, Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief said the current state of affairs doesn’t bode well for the future.

“We cannot build streets fast enough, we cannot build lanes fast enough,” he said of his city’s infrastructure. Fort Worth has 24 designated mixed-use growth centers, and Moncrief says the city is focusing on improving residents’ quality of life “with minimal impact to our environment [through] orderly and sustainable development.”

Even so, Fort Worth doesn’t yet have a green-building ordinance in place.

Frisco Mayor Maher Maso, meanwhile, inherited a residential green-building program that was adopted in 2001. Since that time, about 12,000 homes have been built to so-called Energy Star standards. A green-building ordinance requiring commercial construction to comply with the EPA’s Cool Roof Program and to meet construction waste recycling standards passed in 2006.

“Of course, you get some pushback when you try something new that’s outside the regular model,” Maso said. “We try to do it by leading by example; we haven’t asked the development community to do anything that we haven’t done.

“The first question that comes out is, ‘How much is it going to cost me?’ We turn it around to, ‘How much is it going to help you?’”

|

| ANATOMY OF A GREEN BUILDING Corgan Associates’ West End headquarters was awarded LEED silver standing earlier this year. Here’s a look at how Corgan did it. 1. High-performance glazing on windows keeps the heat out. 2. The site was once a brownfield, and special parking is provided for carpoolers. photography courtesy of DVDesign |

|

| 3. A common stairwell in the middle of the office reduces elevator use. 4. Natural light filters down the central airshaft and keeps energy bills low. 5. The interior was constructed with regional and recycled materials. photography by Charles David Smith |

‘IT’S JUST GOOD BUSINESS’

Green is the next big thing in commercial real estate, experts say, and it’s only a matter of time before even the most recalcitrant builders hop on the bandwagon.

According to National Real Estate Investor, an industry publication, 77 percent of developers surveyed in 2007 said they expect to own, lease, or manage green properties by 2012. The Building Owners and Managers Association has guidelines in place to facilitate “green leasing,” a deal worked out between a building’s owner and tenant to jointly meet sustainability standards. And many companies across the country have begun allowing employees to telecommute, or have implemented a four-day work week, in order to save on energy costs.

“Most users and owners are going to try to do things that benefit the costs of operations on buildings without the city telling them” to, says Greg Wilkinson, CEO of Hill & Wilkinson Ltd., a Plano-based commercial construction company that has built schools, health care facilities, and even a car dealership with a focus on LEED certification. “It’s stuff that we’re already doing anyway. It’s just good business.”

Wilkinson, a former president of the North Texas chapter of the Associated Builders and Contractors group, says the local industry is abuzz with news of the Dallas ordinance.

“It’s certainly a topic of discussion and certainly a topic of concern,” he says. “What I’ve learned about the city’s stance so far is that they’re going to ask for the lowest level of certification that LEED has. We think that that is not going to be that difficult to achieve, if the owners and the architects understand [the process].”

Perhaps the biggest concern stems from the possibility that companies from outside Dallas that plan to relocate or build offices here will not be aware of the new ordinance. Once they discover the new rules, plans may need to be redrawn and OK’d by the city, which could delay construction and increase costs.

While the process of following the green-building ordinance may not be terribly complicated, there are loopholes that allow some construction to appear greener that it really is.

“It has been very interesting going through the process of getting to a LEED-certified position,” Paris Rutherford, president and COO of Dallas-based ICON Partners, said during a recent panel discussion on sustainability. “What we’ve noticed is that you can go through and click a lot of things that don’t really matter [and skip over the things that do]. You can get right over that threshold.

“I didn’t realize you could do that with LEED, but there are certainly some tricks you can play with it,” Rutherford said.

Dallas officials realize the system could be “gamed.” So they’re trying to keep builders from skipping important points by requiring credits for energy reduction and responsible water use, among other things.

|

| IT’S EASY BEING GREEN: Jessica Warrior, one of Jones Lang LaSalle’s LEED experts, says a shift toward greener building practices has just begun. photography by Adam Fish |

“Greenwashing is something that we cannot prevent, but [knowledge of] it only helps to put people in the right direction,” says Basora, who will be one of a handful of people responsible for enforcing the new code once it takes effect next year.

When it comes to greenwashing—presenting your building or company as more environmentally friendly than it really is—architects are sometimes the culprits. Kirk Johnson, a project manager in the Dallas office of the Corgan Associates architectural firm, says he’s seen instances of greenwashing among the competition, though he declines to name names.

“In general, across America, there’s a lot of greenwashing,” he says. “People don’t know what green really means.”

Corgan is involved in 24 LEED projects, including the performing arts center in downtown Dallas, which is expected to qualify for LEED silver status. But the company’s most notable green effort is its own headquarters in the West End, which was designed by Corgan architects to meet LEED silver standards. The upfront cost of using environmentally friendly products and services there, Johnson says, was minimal.

“Before it hit the mainstream, the perception was that it was going to cost a lot,” he says. “That’s changing, and a lot of it is government. Dallas is at the forefront of that, and I applaud them. It’s the right thing to do.”

According to the October 2008 Jones Lang LaSalle Energy and Sustainability Reference Guide, the cost of a green building is 1 percent to 7 percent higher than a typical “non-green” building, with returns on that investment expected within the first 10 years.

Dallas’ new ordinance is “going to change a lot of things in Dallas with the construction industry,” Johnson says. “The industry as a whole has kind of grappled with what is sustainable, and that’s going to change as they get more aware.”

While the construction industry may sometimes be slow to embrace the green phenomenon, the corporate world has reacted much differently, experts say.

“Companies want to be in green buildings, and they’re willing to pay a little more,” says Jim Yoder, a managing director of Jones Lang LaSalle in Dallas. “If there’s a tie-breaker situation and one is green and one is not, the green is going to win.”

Yoder’s coworker, LEED-accredited building manager Jessica Warrior, sees it as a numbers game. “When you heat and cool an entire building with dated equipment, it’s just gobbling up energy,” Warrior says. As green energy sources and supplies become cheaper, more people will gravitate toward them, she contends.

Warrior says this is the beginning of a major shift in the commercial real estate market. “Over the next five to 10 years, it’s going to become a way of life. To have to meet these energy benchmarks with the city of Dallas, it’s huge.”

Like Warrior, Yoder is optimistic about the success of Dallas’ green-building ordinance, given the positive response from the commercial buying and leasing sector so far. “I think it’s great that Dallas is taking on green building, especially given Texas’ energy reputation,” he says. “That’ll be a feather in our cap.”

If members of the Dallas business community embrace the city’s new, environmentally friendly image, Basora and her team may have a relatively easy time enforcing the green-building ordinance. But it’s unclear what the response will be next year.

People at the city expect things to go smoothly—so long as word of the ordinance is disseminated effectively. “We want to make sure that there is information out there,” Basora says. “We’re developing tools for the builders so that they know what to expect when they come for a permit next October.”

Among those tools are training and other types of partnerships with The Real Estate Council, the American Institute of Architects, and the U.S. Green Building Council.

But, Dallas’ green revolution isn’t going to end there, by any means. After phase one goes into effect next fall, the city plans to roll out an even stiffer version of the green-building ordinance in October 2011.