In its 1993 application for national designation as a historic place, the Tenth Street Historic District is referred to as Oak Cliff’s “most important African American neighborhood.” Yet the document reads like a last gasp—by the mid-’90s, demolition had become “the neighborhood’s main adversary,” a reality that means “very few historic commercial buildings have survived.”

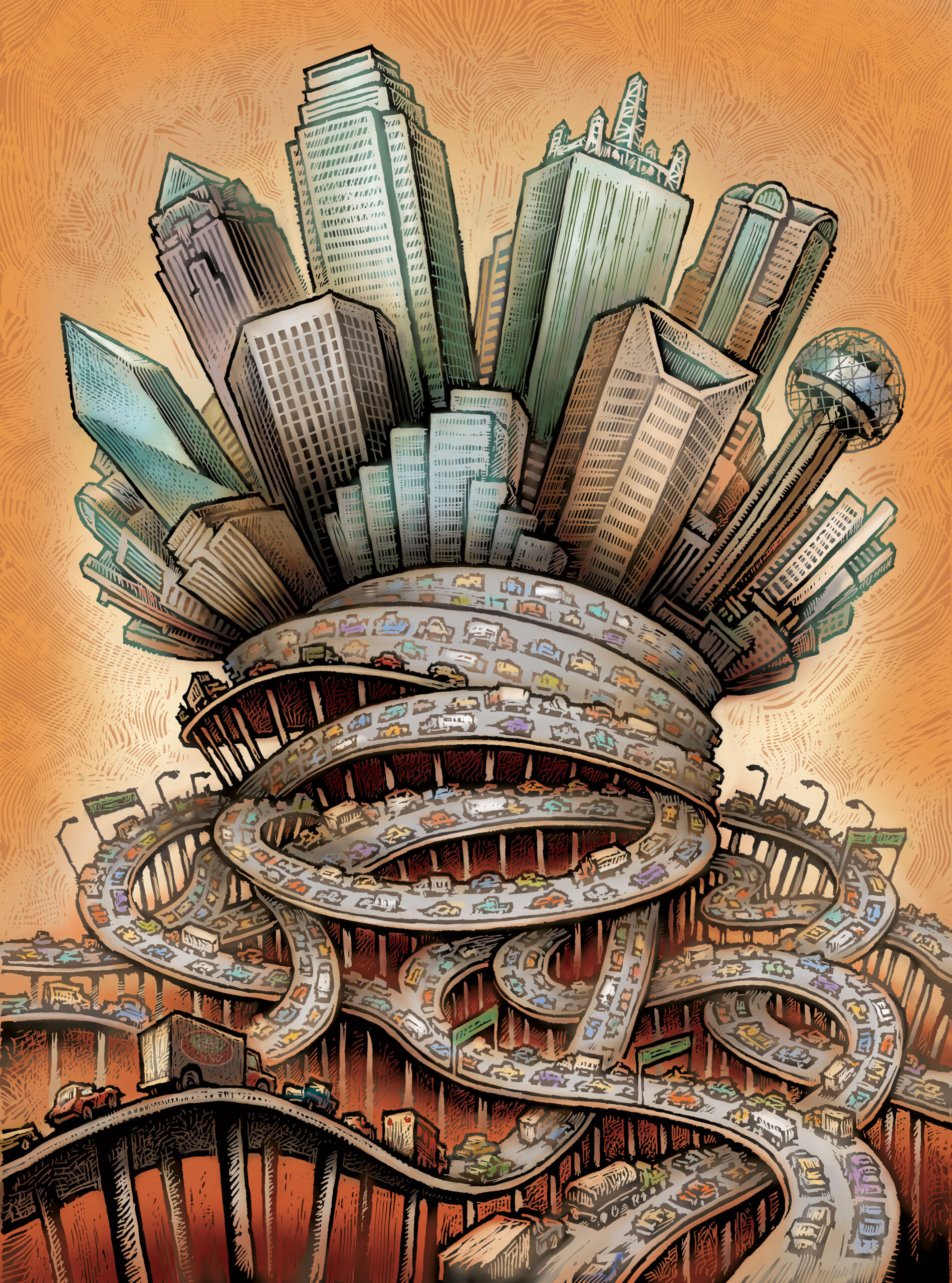

The true enemy is mentioned both as boundary and instigator; Interstate 35E, built in 1959, cut this neighborhood away from the rest of Oak Cliff. The momentum this majority-black community had gained throughout decades was erased in a flash by a concrete barrier meant to ship drivers north with ease. The results were felt acutely but remain stubbornly present half a century later: disinvestment, economic destabilization, and housing disruption crippled its population, and it never recovered.

Kathryn Holliday, the director of the UTA’s David Dillon Center for Texas Architecture, explores this idea of highway as neighborhood decimator, particularly of minority communities in Dallas. Writing for the Dallas branch of the American Institute of Architects’ Columns magazine, she associates the 1959 construction of Interstate 35 with both the economic disinvestment in the Tenth Street District and the racial violence that followed its residents after they were forced to move.

Holliday writes:

“Discussions of urban blight and “undesirable” populations may have partially sanitized the language of the planning process, but in the eras of Jim Crow and the postwar civil rights movements, these huge infrastructure projects played a key role in creating and enforcing an urban geography that privileged the priorities of civic elites at the expense of minority populations. This was the case not only in Dallas, but in cities across the country that used federally and state funded highway construction to enact local policies of discriminatory urban renewal.

These stories should matter to us today because they helped create the foundation of the city that we live in together. The city is not a level playing field. Constellations of federal, state, and local policy targeted minority and low-income neighborhoods for disinvestment for decades and the consequences of those choices and policies remain with us today.”

She notes that this is hardly the only freeway to lay waste to a minority community in Dallas. This portion of R.L. Thornton Freeway was built after Central Expressway (in the 1940s) and about three years before Woodall Rodgers. The one-two punch of Central and Woodall signaled the destruction of the majority-black Freedman’s town neighborhood near where North Dallas High sits today. Bonton and Lincoln Manner were damaged by Central’s southern appendage and C.F. Hawn Freeway. I-345 in the 1970s bisected Deep Ellum and downtown, making sure the two would stay apart for as long as it remains standing.

It’s plain to see the consequences this construction had on southern Dallas. As Peter Simek notes in his recent D CEO feature on the mayor’s GrowSouth investment initiative, Dallas’ southern sector accounts for about half its land mass but only 15 percent of its tax base.

These freeways are border vacuums, objects that block connectivity between two places, but they are more than that—insidiously planned actors of antiquated urban policy that took minority neighborhoods for real estate and little else. Holliday’s grim narrative continues through the 1960s, when Little Mexico fell first to Harry Hines and then to the Dallas North Tollway, ushering in further demolition and displacement for the Latinos who lived there. “Highway development proceeded in parallel with housing policies created by the Federal Housing Administration to undermine the economic viability of minority neighborhoods.”

The feds granted Tenth Street historic designation in 1994, and last year the Texas Historical District issued it a marker. But let’s go back to that designation application, which paints an important picture of what the neighborhood was. The Tenth Street District, it notes, was likely first populated by African Americans who’d been freed from the grasp of Dallas cotton farmer William Brown Miller. They built a church, the Elizabeth Chapel. A school came in 1886, near what currently is 12th and Lancaster. More extensive settlement began in the late 1800s and continued. The growing population, combined with the restrictive Jim Crow laws, created what the application refers to as a “dynamic, largely self-contained community.” Residents worked industrial jobs at J.G. Fleming & Sons and at the Oak Cliff Paper Mill. They opened grocery stores, barber shops, bars, doctor’s offices, pharmacies. In the ’20s, Tenth Street had grocery stores at either end.

The homes grew larger, and middle-income doctors, workers, and business owners moved in. The downturn of the neighborhood began with the end of the Jim Crow policies: “African Americans were no longer a captive audience for local merchants.” Then came Interstate 35, which further destabilized the community.

“The historian Raymond Mohl has called attention to the ‘devastating human and social consequences of urban expressway construction’ because of its lopsided impact on the communities of color it displaced and the white middle-class suburban populations it served,” writes Holliday. “Acknowledging and understanding that our shared urban history contains both utopian optimism and structural inequality is a necessary first step in considering how to move forward.”