Last night, Jeff Tumlin, a transportation planner who has worked in cities from Seattle and Vancouver to Moscow and Abu Dhabi, spoke to a half-packed auditorium at the Magnolia Theater in the West Village about the state of Dallas transit. The talk was the opening event in a transportation summit which continues today at the Latino Cultural Center and is hosted by the AIA Dallas and the Greater Dallas Planning Council.

The summit offers an opportunity to pause the ongoing conversation about transportation and take stock of where we are and where we are headed. Thus far, this conversation has latched onto a few key issues: killing the Trinity Toll Road, advocating for the boulevard-ing of I-345. But in his talk, Tumlin urged the city to take a step back from debating specific infrastructure projects and instead take a system-wide look at how transportation policy is developed in the region and how it can best address the challenges that face DFW as it strives to remain competitive in the next century.

Dallas, Tumlin said, is at a critical moment in its history. On the one hand, it has done a number of things very well, such as building out an interstate system that has facilitated robust regional growth, while making efforts – notably the trenching of Central Expressway – to minimize those roads’ impact on urban growth. However, as we all know, the city and the region has done a number of things very poorly, namely creating a transportation system that has exported value from the center of the region to its northern suburbs. “All transportation systems should create value, not move value around,” Tumlin said.

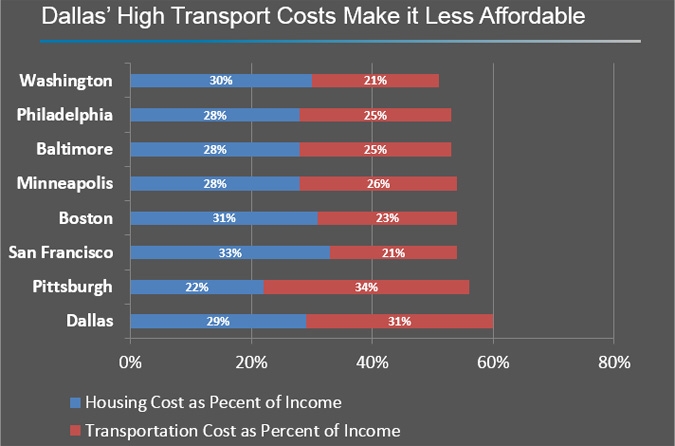

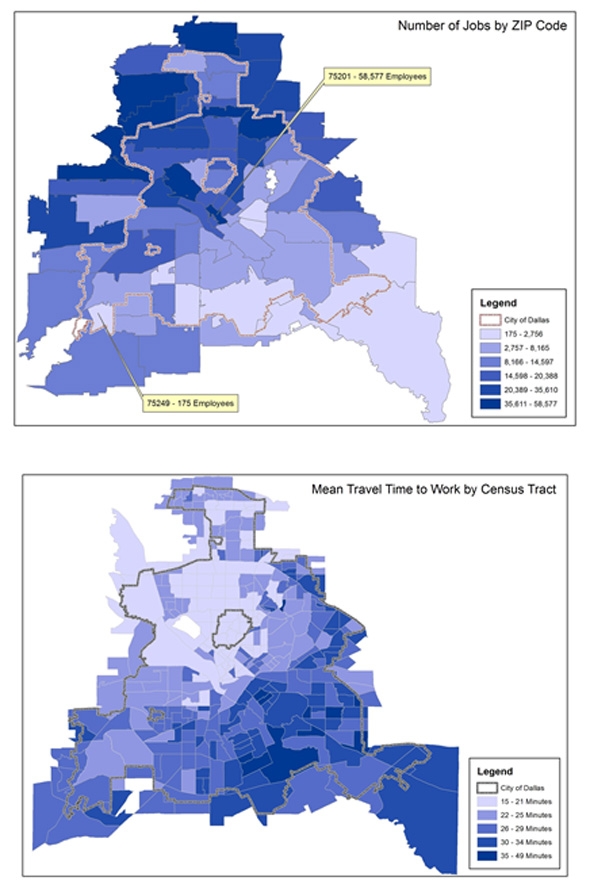

Tumlin showed a couple of data-driven graphics that illustrated the point: the region’s jobs are in north, while the burden of costly commutes falls disproportionately on those living in the south. This distribution of jobs presents a bigger problem than just a perpetuation of social inequality. Dallas is the third worst metro for rising costs vs. income growth, Tumlin said. In other words, we’re not maximizing the productivity of our citizens, in part, because of the way the region has structured its transportation system. Tumlin pointed to calculations which show that it’s cheaper to live in San Francisco or Boston than Dallas once you factor in this city’s high transportation costs.

Here’s where you would have expected Tumlin, who has worked on the removal of two inner-city highways in San Francisco, to take a bite at the I-345 jugular. But he didn’t. Instead he pointed to a simple reason why Dallas, a city that has produced numerous well-considered plans for building a more efficient, sustainable, and urban core, has failed to realize the urban vision laid out in those plans. Goals and visions have to be translated into quantifiable objectives and qualify-able metrics, he said. In other words, planning documents are great, but unless they are translated into the language of the people who are implementing transportation policy — people like the bureaucrats at the NCTCOG — then nothing will ever get done.

The most interesting aspect of Tumlin’s presentation for me revolved around his grappling with the way the language and values of the various people involved with creating and implementing transportation policy often create the barriers that preclude the creation of a more effective transportation system. “Level of service,” a wonk-ish phrase traffic engineers use to describe efficiency, has an inverse relationship to the kind of economic activity that facilitates urban growth. A-grade “level of service” means fast-flowing interstates to a traffic engineer, while A-grade urban spaces to an economist implies a certain amount of congestion and density of activity. Similarly, building roads to reduce congestion is a cyclical process which induces new demand, putting pressure on expanding the network capacity. It’s self-defeating. This is an idea we’ve harped on again and again in the I-345 conversation, but Tumlin located the root conflict in the simple reality that congestion is a function of economic forces — an increased need for people and goods to move – and yet we try to address the problem with infrastructure solutions. “For any economy, a gross oversupply is seen as a bad thing,” he said.

There were more examples of this kind of disconnect, but Tumlin’s main argument was that before we can really address ideas like boulevard-ing I-345, we need to take a systematic, system-wide view of transportation in Dallas-Fort Worth and rewrite our vision in a way that can then be translated into implementable objectives and metrics. The transportation system must be reconsidered in a way that maximizes the region’s productivity. That means ensuring that suburbs are still tied to an efficient road network, but it also means making downtown a “premiere address” able to attract jobs and transform into the kind of economic engine that urban cores should be. This will help attract jobs closer to the center and closer to Southern Dallas, easing the transportation burden on the city’s poorest residents, who happen to also be the city’s most under-realized asset. Tumlin also warned against looking for a “silver bullet” in South Dallas, and speculated that most progress would be a product of a thousand small projects. As for improving Dallas’ public transportation, he urged the city to look at how Los Angeles manages its bus system, which is an extremely efficient and effective means of getting around – the “work horse” of the car-centric’ s city increasingly usable public transit system (hmm, that sounds like an idea we’ve heard before).

Tumlin’s comments come at an intriguing moment in this city’s history. There is an increasing sense that more and more people understand that changing our historical approach to transportation is absolutely necessary if this city is going to compete on a global scale in the coming century. There seems to be a real consensus that we are at a turning point. We can continue to develop as we have, with its region-minded patterns of growth, or, we can take a comprehensive look at the regional economy and figure out a way to design a transportation vision that maximizes the strengths of each part of the Dallas-Fort Worth. That means figuring out how to truly address things like creating urban density, facilitating inner city job growth, and building a better public transit system. “Downtown,” Tumlin said, “Is the only place in the region where the market will produce transit accessible employment.”

This all gets us back to the real situation of the debate as it stands today. Whether or not you buy into the idea of rerouting, burying, or removing highways in central Dallas, the real pressing question now appears to be that of figuring out who, exactly, is dictating our transportation policy and vision. On the one hand, we have civic leaders who are increasingly vocal about the need to refocus on maximizing the potential of central Dallas. On the other hand, we have a regional planning organization that continues to roll out plans for creating hundreds of miles of new tollways. These visions are contradictory, the product of muddled policy, incompetent administration, bureaucratic obfuscation, and weak political will power. Before we can address the transportation crisis, we must address the governmental crisis.

Regional policy bodies like the Regional Transportation Council are dominated by voices representing the interests of the suburbs, and the voices from the urban areas of the region have proven either ineffective or vague. What we need now is real, vocal, and audacious leadership that can assert the city’s best interest. We need leaders who can effectively argue the case that the real economic power of the region in the coming century rests in realizing the power of an urban center that functions as an economic engine. Rather than squabbling over road dollars that facilitate immediate investments and development in the outer region, the competing municipalities must realize that the suburbs’ best interests in the long run lie in supporting the growth of a city that looks like all great cities have looked throughout history: a strong core that pumps economic life outwards. It’s time for people like the mayor and the county judge to step up. Put the right representatives on the RTC, and bring in people like Tumlin who can effectively translate a real vision into metrics, municipal goals into regional priorities.

“The decisions you are going to make in the next two years are going to shape Dallas for the next 50 to 100,” Tumlin said. “This is a moment for Dallas. Dallas can be one thing or it can be something completely different.”