On my way to see American Modern: Documentary Photography by Abbott, Evans, and Bourke-White, at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art last week I got tangled in a maze of construction traffic in the burgeoning mixed-use neighborhoods nearby. Roads were blocked off, lights were out, and I had the darnedest time getting my bearings in a place I found incredibly altered since I last was there. In an attempt to escape the congestion, I made a turn down a street called Museum Way, thinking, not illogically, that that road must lead to the row of museums. Instead, I passed a legion of construction workers leaning on shovels, carving out, I soon realized, a new luxury community of various styles of homes all jumbled together on tiny little streets called names like Matisse Way, Picasso Way, Calder Way. There was no way out, except back the way I came. So back past the workers I went. They eyed me mockingly. I wasn’t the first traveler to get duped by that ill-named, dead-end road.

When I finally did find my way to the Amon Carter and up into American Modern, my little detour through new-fangled urban development felt oddly serendipitous. Here was a show cataloging the by-gone era of skyscraper building, American-made mass production, and poverty so down-and-out dismal it seemed staged. The work here highlights the tenuous relationship between progress and history, documenting the frenetic everyday life of cities and their machines, but also the slower, suffering lives of the rural poor during the 1920s and ’30s. The three photographers featured are Berenice Abbott (1898-1991), Margaret Bourke-White (1906-1971), and Walker Evans (1903-1975). With many shared themes, each brings to the forum a particular lens angle on life in America during one of its most tumultuous, yet productive, times.

Margaret Bourke-White’s pictures of rows of shoes and silver spoons that vanish off in the distance hint at the endless pumping-out of mass produced goods, while her shots of various dams, wind tunnels and enormous machine gears or electric towers convey the muscle power of industry. Almost always, Bourke-White catches a hunched worker in the frame that is dwarfed by whatever built machine he is laboring with. This primarily conveys a sense of scale, but also suggests the subjugation of the worker to the machine under the machine’s colossal footprint. The composition of Bourke-White’s photos tends toward an angled, perspectival view if whatever she is looking at, sending the image up or down the frame like a list: smokestacks, the cavernous interior of a steel factory, aerial streetscapes, men sitting along a curb clasping their hands on their knees. Her pictures readily recall the photos and paintings of Charles Sheeler with their high contrasts in hue and penchant for industrial milieus. Like Sheeler, Margaret Bourke-White itemized the world through her lens.

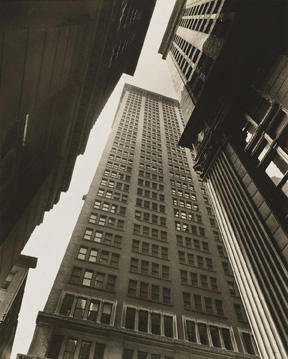

Many of Berenice Abbott’s photos of the caverns of downtown New York, looking up to the tops of buildings and down streets lined with skyscrapers, seem as if they could have been taken yesterday. But then there are pictures where she has captured her immediate surroundings, the city in the ’30s, as in the picture Herald Square where a flood of summer-clad people — men in derbies, women in white ankle length dresses — move across a busy street full of boxy cars. More than anything, Abbott was interested in watching the shape of the New York grow and change by documenting the construction of new buildings, or looking at the skyline after new buildings had been added. Some of her most stunning shots are of the foundation of Rockefeller Plaza being laid in the thick bedrock beneath Manhattan’s surface. These pictures, taken around 1932, give off an Egyptian pyramid-building era sense of the monolithic task that erecting such a building as Rockefeller Center was. In them, giant I-beams crisscross into the bedrock to create the stability for the enormous structure that would grow above. Abbott made pictures that didn’t allow for the trivialization of the force of America’s urban spaces; she plunged into unearthing what was beneath the surface, but she also catalogued everyday life on the streets in any number of pictures that show the movement of commerce and culture as played out in common activity.

Perhaps the most well-known photographer in the trio here at Amon Carter is Walker Evans, whose pictures of American workers in cities and rural areas have become iconic portraits of life in this country as it struggled through the Depression. My favorite here is one called Alabama Tenant Farmer (Allie Mae Burroughs), 1936. It’s a headshot of a woman standing against a clapboard wall. Her skin is pale and tight, and her lips are narrow and smileless – as rigidly horizontal as the boards she’s leaning against. Her forehead is furrowed, with her black hair pulled tightly back behind her head. It’s hard to tell how old the woman is – 28? Forty, maybe? She has a weathered look, but ageless too. She glows with a kind beauty, and while we see none of the accoutrements of her daily life, the work she does is written on her face. It’s a perfect portrait.

Evans’ other pictures of places: the white, crumbling breakfast room of a Louisiana plantation; a row of white frame houses in Virginia; or a boarded-up, but glowing white sharecropper’s cabin all carry with them the same power of personality as Allie Mae Borroughs. Each place resonates with a history that is becoming more and more the past.

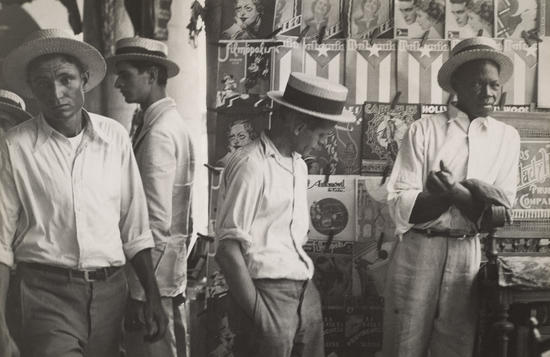

Evans’ pictures of workers, both in the States and outside of it, almost always look at the worker head-on, acknowledging each person’s identity and letting their faces describe their labor. A beautifully composed shot of three coal workers in Havana, Cuba, shows men covered in coal grime. The man’s skin at the bottom of the frame is stained so black that only a sliver of the white of his eye and the inside of his lip stand out in contrast to the rest of his face. These men take on, quite literally, the effects of their labor.

All three photographers here in American Modern at one time or another were commissioned to document life in the rural South. Each photographer captures a quality to life in the South that stands in direct opposition to the towering progresses of construction in the Northern cities — the poor sit hunched, weary, and desolate in many of these pictures. Alongside the clean and managed shots of industry and commerce, these photos of the poor show a portrait of America that even now, a decade into the 21st century, could find new iterations, though few are looking for them anymore.

Main image: Walker Evans (1903–1975) , [Lunchroom Window, New York City], 1929; Gelatin silver print (© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)