Last summer, I paid a visit to the Lakewood home of dentist and Renaissance man John Zotos. He has an excellent collection of works by North Texas artists from what I would describe as Dallas’ golden period—about 1997 to 2012—complemented by works from farther afield. He had two early paintings by Raychael Stine from her 2007 debut solo show at Road Agent, a short-lived (but exceptional) Dallas gallery owned by my then wife, Christina Rees. I hadn’t seen the paintings by my long-lost friend since that show. They blew me away.

So it was with great joy that I went to see the opening of her current exhibition at Cris Worley Fine Arts, on view through May 4, with whom I’ve had a working relationship for several years. And now, this Saturday, April 20, Raychael will return to Dallas, the city that launched her career, where we will reunite in an artist’s talk about her current show and an opportunity for all to ponder, if I’m right, to think this exhibition is Raychael’s finest yet and a time portal back to that golden period in the city.

Her newest paintings are wonderfully sumptuous, exuberant, and emotional. Neither expressly abstract nor figurative, they can appear simultaneously like invented interiors, landscapes, and figures. Vivid and alive, the paintings thrum with energy bursting forward as if they’re in motion; the diaphanous color and the large gestures feel musically expressive, as if at times you’re almost seeing sounds. They’re complex without being fiddly and have a supreme emotional joy that makes viewers feel as if they’re painting along with her.

There are worlds within worlds. The paintings are packed with eclectic influences: from other painters, from the natural and unnatural worlds, but never worn heavily as self-conscious post-modern references but instead as original and confident modern art. Standing in front of them, you find yourself getting sucked into the painting space, examining what exactly is going on in this “Wonder Dawn,” the title of her show. Are her paintings cosmic? Did taking off for the New Mexican desert in 2013 make her go a bit woo-woo, this once teenaged prodigy from Ohio who grew up in New Jersey and then the suburbs of Dallas? The paintings often have the look of an electrically back-lit computer screen—not self-consciously digital but merely containing their own power and light source, as if they’re permanently switched on.

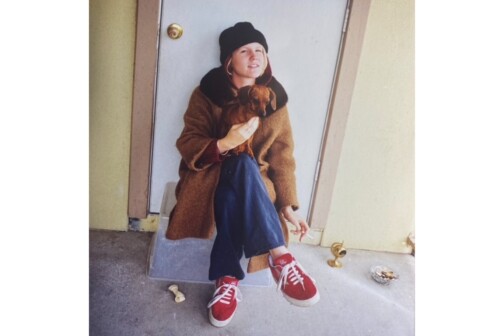

Raychael’s principal motif for many years was her own pet dogs—namely Pickle, the dachshund, and Hal the chihuahua. The dogs made many appearances in her paintings, along with rats and weasels. They were surrogates for people, trustworthy and reliable companions, not sentimental pet paintings. They inhabited abstracted looking spaces of empty flat color, often in Camille Corot palettes, sometimes kept company by clusters of abstract brushstrokes fighting for airtime on the canvases.

In “Wonder Dawn,” if Corot lurks at the back, a mid-1970s soundtrack from the Todd Rundgren album Initiation accidentally spills forward, all of this is somehow transported courtesy of Howard Hodgkin and David Hockney. Raychael is an admirer of many British painters, including some of the YBAs, not least perhaps Gary Hume, whose influence can be seen in her flat color and graphic shapes in some of her earlier work. Mixed in somehow—and this fits with her life story—is something of the Parisian fantasist Henri Rousseau, who painted stylized jungles, but as if seen from the comfort and habitat of the city dweller.

How did Raychael get to the point she’s at now? To continue my prog rock cosmic theme, I’ll borrow the title from a 1972 ELP ballad.

You see it’s all clear

You were meant to be here

From the beginning

From the Beginning: Rachael Stine, without the Y, was born in 1981 in Chardon, Ohio, the younger of two daughters. Her family hailed from Bohemia, Slovenia, and Yugoslavia, with a bit of Dutch and German mixed in. Both grandmothers were first-generation American and came from the Cleveland area. Until she was 7, her family lived in Ohio, where Rachael attended one of the state’s Notre Dame Convent schools. Each morning she was driven by her parents into school through apple orchards. When the fruit was ripe, nuns stood on step stools in their habits and picked the apples along the avenue that led to the school. The view out the car window made an impression on Rachael, a scene somehow conjuring the South of France or Black Narcissus, the 1947 drama about Anglican sisters trying to establish a school in the Himalayas. Raychael’s nuns made non-alcoholic cider from the apples and sold it to the parents and students.

In 1988, Sister Jane already had Rachael pegged as a great artist and regularly pinned up her drawings and paintings in the school dining hall and common spaces. No other student was afforded this honor. Sister Jane labeled the work: “Rachael Stine: Budding Artist.”

Rachael’s school experience was flipped through 180 degrees when her parents moved to Sussex, New Jersey, where she entered state elementary school for a year. Her new best friend Chrissie was part Puerto Rican, part Irish. Her father was New Jersey’s chief of police and reputedly, her mother had been a prostitute who the father rescued from the street and then married.

At 8 years old, the youngsters discovered New York’s Hot 97 radio station, and zoned in on the scene that produced new jack swing. Think dance pop and hip-hop, synthesizers and sampled beats. She credits this musical exposure with forming much of her character and perhaps some of her sense of aspirational adventure, which was soon to be channeled into art.

Being wrenched from convent school to state school had another effect: her precocious fascination with music and intense MTV watching, combined with her demeanor, created the impression she must be satanic. In fact, she herself decided she was satanic and began turning crosses upside down while wearing only black and red.

By 1991, the family had moved south to Double Oak, in Denton County. Her preconceived notion of Texas was Pecos Bill, and she was wondering if she was destined to a life of gingham and riding to school on horseback. Rachael was now wearing a lot of crystals and had a flip bob hairdo. She was heavily into ’90s house music. The art kid stood out as weird and different, and she was made fun of. One of the teachers dubbed her Toxic Waste Lady and encouraged the other kids to call her that.

Rachael’s nickname was Ray. At a certain critical point, sometime in her early mid-teens, she began to buy her clothes at Slix, which specialized in Latex bondage gear, and she officially added the Y to her name to become Raychael. She hastens to point out, I guess like all good convent girls in bondage: “In actual fact, I was really an extreme prude at this point in her life.” Nonetheless, by 16, Raychael was already a precocious talent and dressing like she was on the cover of Lou Reed’s Rock and Roll Animal.

But the culture shock of moving to the conspicuously Christian and Baptist suburbs of North Texas left Raychael not knowing what to expect. By the time she reached Lamar Middle School, her friends found Ray so officially weird that people began first to ridicule her, then to save her. Her new best friend at school, a girl called Crystal, was the daughter of the organist at the notoriously corrupt Robert Tilton Word of Faith Church. Her best friend soon spread rumors that Ray was a baby-eating witch and that she was using her powers to put a hex on her and put gum in her hair. The two girls fell out shortly after.

To let discretion be the better part of valor and not dwell overly, it would be fair to say her family life was dysfunctional. Her older sister left home at 16 to join a cult. Raychael learned to be independent and to find solace and belonging in her own invented belief systems; to find her own way, and as with so many adolescents and teenagers, she found solace and passion in music, fashion, art, and, of course, her dogs. Her description of her childhood sometimes sounds like the story of Oskar in The Tin Drum. She needed to invent her own private world early on as a coping mechanism. This world grew, I think, into her art practice.

Real salvation for Raychael came in the form of a high school competition and two surrogate parent figures, Greg Metz and John Pomara. This is where Raychael’s story and the story of the Dallas art scene’s golden era happily converge.

The dean at UTD was looking to launch a fine art course that could compete with UNT’s—the school famous for its music department, but also its stand-out art department, run by Vernon Fischer and others, and famous for nurturing the GoodBad Art Collective, its principal members including Martin Iles, Chris Weber, Micah Yarborough, and Erick Swenson.

The dean approached Pomara to build the course. Pomara had three conditions:

1. He needed five years to build the course. It couldn’t happen overnight.

2. He had to hire Metz to be the Jeckle to his Hide, the bad cop to his good cop, the dad to his mom, the roast beef to his Yorkshire pudding. And, despite not having tenure, Metz could not be fired for a minimum of five years. Pomara knew nothing happened in isolation and that teamwork and partnerships and connectivity were vital.

3. Pomara wanted four to five scholarships per year for the new course.

It was Metz who noted that the Texas Visual Art Annual High School Competition—which accepted art submissions from all high school students in the North Texas region and then showed them crudely on stand-up boards at the Plaza of the America’s Ice Rink—was a potential source for intake at UTD, perhaps the only fast way of getting a jump on UNT. But Pomara and Metz agreed the conditions and surroundings were awful and sought to move the competition to more focused and dignified gallery conditions at UTD’s Art Barn, its large studios that housed the painting undergrad course. From this sharpened context, they could impress the dean with what they were scouting.

A year or two into the revamped, rehoused competition’s tenure at UTD, Raychael applied to the competition at around the same time she was graduating high school. She also had applied to the Chicago Institute of Art’s summer school and had been offered a place there but only a meager scholarship. Meanwhile, Pomara and Metz were flipping out over how good her entry into the Art Barn was and instantly offered her a scholarship.

Raychael turned it down because of Chicago. But Pomara and Metz wouldn’t give up. They said they could offer a far bigger bursary and all the dedicated attention and tutoring she’d need and that Chicago wouldn’t be able to offer. Eventually Raychael called Pomara to ask if the UTD scholarship was still on offer, to which Pomara said, and I am quoting him faithfully: “Fuck yeah!”

Pomara told me: “I’ve seen many hundreds if not thousands of students at this competition, and I’ve taught hundreds over the years at UTD. Raychael was one of the all-time top three students I’ve ever seen.”

Both Pomara and Metz stressed how unusual it was for such a young student to stand out this clearly, so much so that she was even given the unusual position of becoming Pomara’s TA while she was a junior undergrad.

And so it came to pass, as it says in the Bible, that Raychael finally found salvation in Dallas—but not in the way it’s usually offered. I bore witness to some of this when I arrived in Dallas in 2000 to show at the Dallas Museum of Art. I was doing a one-person show in their “Concentrations” program, and the forward-thinking Pomara and Metz had already begun to connect the undergrad activities to the DMA. In fact, through Pomara’s friendship with Suzanne Weaver and Charlie Wylie, DMA curators during the museum’s most rock-and-roll era, they persuaded Bonnie Pittman, then director of education, to allow students to come to the opening of my show, despite most of them being too young to be around the (not particularly great) booze that was being served.

I wasn’t to know this at the time. I only found out years later, after I’d moved from New York to Dallas with Christina, and I hired Raychael to work in my studio here. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Back to the salvation:

Raychael told me: “I thought that earning a living as an artist meant being a graphic designer, an illustrator or something like that. But when I won the school competition and then the scholarship, and I met John and Greg, I realized I could be the thing I wanted to be, that there was a pathway and a world of art out there.”

Pomara told me that at the time he said to Raychael: “You have to go see all the shows. Go to David Quadrini’s Angstrom Gallery opposite Fair Park.” The often brilliant, exceedingly charming, and quixotic Quadrini virtually was the Dallas art scene back in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He and Suzanne Weaver were thick as thieves. Quadrini more or less had his own private residency in Weaver’s office at the DMA at the time. Pomara continued: “Go to all the museum shows. Read all the art magazines. Find out who the hot artists are. Steep yourself in all of it. And then just make your work and you will be an artist. You are an artist.”

While Pomara gave the maternal love and unconditional support, Metz gave the tougher love, imbuing a necessary sense of rigor, realism, and process. It was Metz who started classes (of which I’ve been part of) to introduce students to the realities of the collecting world, career pathways, how to value work beyond its inflationary and fickle monetary evaluation.

A major diversion that will bring me, I promise, to a salient detail: Metz told me a wonderful story about the Yale Summer School for Music and the Arts he attended in 1967. When the students were tasked with displaying their work for critique in a large barn, the guest artist was the legendary Philip Guston. Metz’s own work stood out as “wrong” or not in vogue with all the then fashionably earnest fourth-gen abstract student painters who were also present. The incredibly erudite Guston—who was on the sauce (bourbon) at the time and not hiding it—abruptly announced that everything in the barn was complete crap, except for one piece: Metz’s. Guston then showed the students the first of his infamous late paintings, the ones that every gallerist, every nincompoop collector and critic totally trashed as abysmal, dreadful, artless bad taste cartoons etc. This was Guston, the painter’s painter, later to become the Messiah of “Bad Painting” and still worshiped to this day around the art schools, museums, and private collections. The Yale faculty gasped as he revealed this new work. No one knew what to think. But Guston liked Metz’s painting and only Metz’s painting. Later, Metz worked as a TA alongside Josef Albers’ TA. Albers was an esteemed painter and then the head of the design department Yale. Albers’ work was all about color. From the TA, Metz absorbed all Albers could impart about his extensive understanding of color theory—and from this, Metz imparted to students at UTD.

Color, that is the salient detail. Have a look at Raychael’s color. Have a look at it in real life. We worked together in my studio for three years. Most of her job, when not inventing dances—like the one to Rundgren’s helium-fueled track “Determination” (which is pretty much her theme tune)—was precisely mixing ultra-closely graded colors to charts. My other assistant was Evan Lintermans, who’d worked with me in New York and had come with me to Dallas. Evan did much of the drawing, Raychael the color. The aim was eventually they could make my paintings for me, and I could sit in the Meridian Room next door and drink cocktails in the seat barely cold from where Quadrini sat, but we never quite got to that point. Although we almost did.

My fondest memories of our time together was her daily question on walking in at 10 a.m.: “Where are we going to eat lunch today, Ricky?” She always wanted to know in advance how the day would pan out. Sometimes I was Ricky Bobby, because I’d dubbed her Raylene, like one of those synthetic fabrics for bed linen from the 1970s that don’t need ironing. I only called her this as a Taladega Nights ironic Southern name, because, in fact, neither of us were properly Texan.

Raychael is a really good mimic and a good cook, two useful traits for the painter. I got her to leave the outgoing message on my studio phone, which stayed on there the duration of the three years she worked with me. In a strong redneck accent, she said: “Uncle Ricky Bobby can’t come to the phone right now, ’coz he’s workin’ on his car.” It was genius. Very funny. I laughed at it every single day, and I secretly hoped an incredibly important museum person or Larry Gagosian would call my studio and that’s what they’d hear.

When Raychael left UTD, she joined a small collective called Oh6 started by artist Kirsten Macy (represented by Barry Whistler Gallery Dallas), a performance artist originally, who had been at the same UTD course but slightly later. Other members of Oh6 included artist and photographer Kevin Todora (Erin Cluley Gallery, Dallas) and John Ryan, who long ago took off for Los Angeles.

Christina first encountered Raychael’s work in a Oh6 collective show at the Residency at South Side on Lamar launched by Rick Brettell, former director of the DMA. Christina said of the work, a large horizontal pink canvas featuring flat graphic Gary Hume-esque shapes and her great Dane dog: “It was very expressive and with great paint handling; aggressive, very confident and kind of exploding out of its own frame.”

Christina was soon to open her own gallery in 2006, the aforementioned Road Agent, on Canton Street, adjacent to Barry Whistler’s long-running gallery. Road Agent became the natural successor to Quadrini’s Angstrom (where Christina had worked for a year). Angstrom had by now decamped to LA. Road Agent was similar, only distinctly different. One or two ex-Angstrom artists showed there. Ludwig Schwartz, Elliot Johnson, and Mycah Yarborough (known then simply as M) all had solo shows. Erick Swenson showed a single and iconic piece in a summer show, even though he wasn’t signed to the gallery. Road Agent ran for three years, until Lehman Brothers’ collapse brought credit and the economy to a standstill. It also bookended what was in hindsight (but was also self-evident at the time) the golden era of the new Dallas art scene, the one that was by then, albeit on a smaller scale, running parallel to the scenes in London and LA.

Raychael went her own route. She got her masters at the University of Chicago after leaving my studio, then spent a year teaching at TCU. She eventually landed a tenured position as associate professor of painting and drawing at The University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. She has shown in group and solo shows in LA, Marfa, Dallas, Chicago, and New York, showing in art fairs around America, and generally selling extremely well.

Looking back, though, a giant door was being opened just about the time Raychael entered college and then left it to step onto the Dallas stage. Art fairs were a new thing and cropping up everywhere in this period. The Dallas Art Fair was yet to be a thing, but the Rachofsky 2×2 event, despite at times feeling like a giant tent for very rich people to play an art version of bingo, was a trailblazing fundraiser with real glamour, and it unquestionably helped give a celestial halo that lit up the rest of the Dallas scene. More than a few beams of light projected to the peasant quarter, the sack-clothed, wooden-toothed artisans and artists of Dallas. The two worlds didn’t really quite touch, though. As hard as both ends tried to reach out like the two hands on the Sistine chapel, it was if there had been a minor earthquake and bits of the ceiling had fallen off, and when some slightly dozy restorer stuck the bits of plaster back on, Adam’s hand ended up on one end of the ceiling and God’s hand was at the other end, still reaching out but nowhere near making meaningful contact. It sounds churlish, only it’s the truth.

In the end, Dallas likes consumption. That’s its forte. There is no such thing as a restaurant where the various groups might meet. There is a class system that simply has no interest in integrating here. It was not like this in London. It wasn’t for lack of trying. It’s just not been in Dallas’ DNA.

But from 1997 to about 2008, the Dallas art scene at the creative edge was running under its own steam, and it had its own thing going on. Outsiders were beginning to talk about Dallas.

Raychael got the benefit of this. Both Pomara and Metz pointed out to me that UTD had spawned a group of close artistic friends. Artists tend to operate best within groups. Proximity and artistic relationships are key. If there was a single thing I wanted to help foster in Dallas, it was this. The issue, I felt, was urban studio space—but I’ll leave that for another time.

Dallas in the golden period, from about 2010 to the Fire Marshal Moment, had indeed been forming such cliques. The burgeoning gallery scene from around 2004 saw the advent of several new galleries and spaces, Marty Walker Gallery, Paul Slocum’s And/Or, Road Agent, the Reading Room, and several others. Eventually the Dallas Art Fair kicked off.

But then, in 2016, the Ghost Ship warehouse fire in California killed 36 young people and changed everything, all the way to Dallas. The ashen truth is, the Dallas fire marshal put an end to all of the really vibrant artistic activity. Small upstart spaces got raided and shut down for what seemed like minor code violations. It all felt deflated, discouraged, depressed.

Raychael had timed it well, however. She was long gone in Chicago and then New Mexico. But she told me that when she entered the Dallas art scene, in the late 1990s, early 2000s, she thought it was wonderful, beginning to feel almost international, stuff happening every single week, people coming and going and passing through.

Dallas had its big moment. It continues to have moments. But those years truly rocked, and everyone knows it, and they knew it when it was happening. The world is now a different place, post-pandemic, quite a wanky one, if one is forced to relinquish one’s most privately guarded inklings. Raychael got to ride out during those years.

But now she has returned to the city that, despite itself, taught her how to feel comfortable as an outsider, how to master light and color, and, most important, how to mimic a Southern accent. The baby-eating witch is only 43 years old. I believe her greatest work yet to come.